reviewed by Matthew Teutsch, Associate Professor of English, Piedmont University

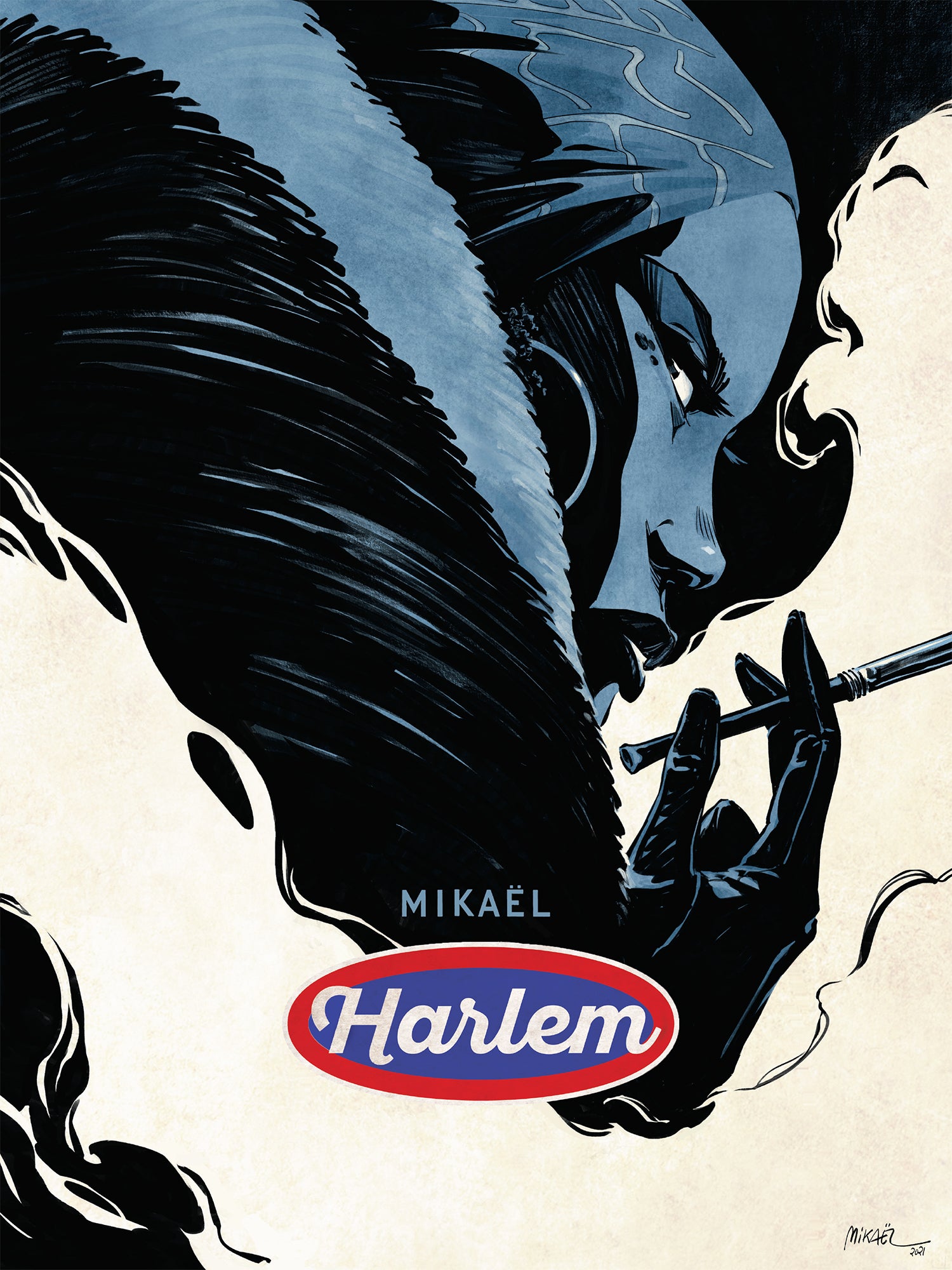

Mikaël. Harlem. New York: NBM Graphic Novels, 2024. https://nbmpub.com/products/harlem

French-Canadian artist Mikaël concludes his New York triptych with Harlem, a fictionalized narrative about Stephanie St. Clair, a woman from Guadalupe who became a businesswoman and racketeer in Harlem during the early part of the twentieth century and the Harlem Renaissance. The narrative moves back and forth in time, detailing St. Clair’s life in Guadalupe to 1930s Harlem. When depicting St. Clair’s early life and eventual immigration to the United States, Mikaël’s color palette changes from more browns and darker colors to shades of purple with splashes of yellow. The yellow, which appears in various objects during these flashbacks from a parakeet to a bag to a light in a window, displays St. Clair’s hope and the hope of others for a better life, one where they can live their lives in happiness and safety.

While on the surface Harlem appears to be a crime narrative centered on St. Clair, Mikaël infuses his story with much more. Mikaël highlights the ways that St. Clair and others navigate, through extra-legal means, a system that keeps them oppressed and subjugated from the highest levels of city government to the police force that walks the streets to other racketeers, notably Dutch Schultz (a white man), who also participates in extra-legal activities. Along with all of this, the community must deal with the ramifications of the Great Depression on their lives. Even as she maintains a hard exterior, St. Clair looks out for the community, providing individuals with hope and resistance, specifically through the pieces that she writes in the New York Amsterdam News calling out systemic oppression.

Ostensibly, the white reporter Robert Bishop serves as the overarching narrator of Harlem, opening the narrative by telling us, “What I did was unforgivable. I know.” By framing the narrative through Bishop, Mikaël allows us an outside view of events. The reader does move into St. Clair’s perspective and the perspectives of others, but Bishop remains the core, and in this manner, he serves, in many ways, like the “white clientele” who flock to Harlem for the clubs and nightlife that Harlem’s residents are barred from entry. Bishop has a relationship with Tillie Douglas, one of St. Clair’s friends, and their interactions highlight the ways that white supremacy did not solely reside within the Jim Crow South or the once colonial regions of the Americas.

Bishop’s connection to St. Clair arises after the editor of the New York Amsterdam News tells her she needs to revise a piece that she hopes to get published in the paper. St. Clair sees Bishop with Douglas and enlists him to help her revise the piece, which he does. In her article, St. Clair lays out what she and the community endure in the face of white supremacy. Over three pages, Mikaël prints St. Clair’s article interspersed with images of individuals getting kicked out of their homes, police brutality, and cultural tourism with whites descending on Harlem for clubs. The sequence ends with the reactions to her piece from Schultz, the police, and her right-hand-man Bumpy. Thematically, this three-page sequence sums up Harlem and the ways that St. Clair pushed back against a system that seeks to keep her and other locked in cages as they bloody their wings against the iron bars.

In “Sympathy,” Paul Laurence Dunbar uses the metaphor of a caged bird beating its wings until “its blood is red on the cruel bars” to describe his position as a Black man at the turn of the twentieth century in America. He concludes the poem with the famous line, “I know why the caged bird sings!” The caged bird metaphor appears throughout Harlem, from St. Clair releasing a bird from a cage in Model’s shop to numerous panels depicting birds flying as St. Clair and others walk the Harlem streets. Harlem concludes with St. Clair returning to the community as residents thank her for speaking in front of the commission and her actions, and the final two panels show birds flying freely in the sky. The first shows birds flying up into the air as we see buildings and a street sign for 125th street. The final panel zooms out, showing the entire New York skyline with flocks of birds in the distance, symbolizing St. Clair’s and the residents’ desire to, as St. Clair tells W.E.B. Du Bois earlier, that she will not “shut [herself] between four walls.”

If one reads Harlem quickly, one will miss many of the historical and cultural references that Mikaël incorporates throughout the book. For example, in a seven-panel sequence following a numbers runner, we see the marquee for Smalls Paradise, one of the only African-American owned clubs in Harlem at the time, and a panel depicting young kids marching with brooms and paper hats imitating the Harlem Hellfighters as a World War I veteran sits on the side. Mikaël also incorporates two poems by Langston Hughes, one at the end of each section. Hughes’ “Harlem” concludes section one, and Hughes’ repetition, in the first and third stanzas of referring to Harlem as “on the edge of hell” drives home what St. Clair fights against. Juxtaposed against “Harlem,” Mikaël ends the book with Hughes’ “I, Too,” where Hughes proclaims his equality and finishes by stating, “I, too, am America.”

Mikaël ‘s Harlem details the history of white supremacy in the United States, colonialism, sexism, and structural issues that impact Harlem and its citizens. It also highlights community and the ideals of America, specifically the immigrant experience and the ways that communities work together to confront oppression and move forward. Through Bishop, Mikaël explores allyship and the need for white individuals like Bishop to listen instead of speaking at times. Bishop gets St. Clair arrested, and as she leaves prison, we see Bishop’s words to her as he types them. He tells her when he envisions her in his mind he sees “[a] look of anger. The anger of an entire people,” and he concludes by telling her, “I only wanted to speak out about the world around me because I thought I had the right to.” Bishop’s words end, allowing St. Clair a voice for herself at the end, a voice that speaks for Harlem.

A version of this review will appear in IJOCA 27-2