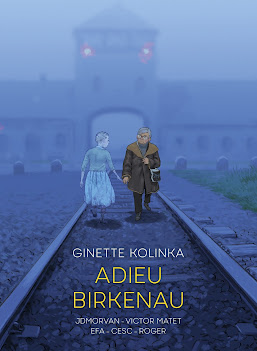

Ginette

Kolinka, Jean-David Morvan and Victor Matet (writers), Cesc and Efa (illustrators),

Roger (colorist) and Edward Gauvin (translator). Adieu Birkenau: Ginette Kolinka’s Story of Survival. SelfMadeHero,

2024. https://www.selfmadehero.com/books/adieu-birkenau-ginette-kolinka-s-story-of-survival

Ginette

Kolinka, Jean-David Morvan and Victor Matet (writers), Cesc and Efa (illustrators),

Roger (colorist) and Edward Gauvin (translator). Adieu Birkenau: Ginette Kolinka’s Story of Survival. SelfMadeHero,

2024. https://www.selfmadehero.com/books/adieu-birkenau-ginette-kolinka-s-story-of-survival

If one were to compile a list of the subjects most-featured in Jewish graphic novels, the Holocaust would surely be the topic that has garnered the most attention. Since Art Spiegelman’s Maus was first serialized in Raw in 1980 and then subsequently published in two well-received and successful collected volumes in 1986 and 1991, license was afforded to authors and illustrators to creatively explore the Nazi-perpetrated genocide of 6 million of Europe’s Jews.

As the 21st century nears its quarter mark, the proliferation of graphic narratives about the Holocaust has not slowed despite the increased chronological distance from the original tragedy. In the past three years alone, a variety of works in English have been published that explore different facets of the Holocaust. This includes grandchildren trying to understand their grandparents’ experiences (Solomon J. Brager, Heavyweight, 2024; Jordan Mechner, Replay, 2024), child survivors telling their own stories (But I Live, 2022), speculative stories about what Anne Frank would do today were she alive (Ari Folman, Where is Anne Frank, 2022), and the horrors of the Holocaust on American soldiers (Leela Corwin, Victory Parade, 2024). Added to this group is Adieu Birkenau which first appeared in French in 2023.

Adieu Birkenau tells the story of Ginette Kolinka’s life from before the Holocaust and what she endured during it. The graphic autobiograhy was produced by a team of creators that included three writers (including Kolinka), two artists, and one colorist. The work is set in both the past and present, with readers learning about Kolinka’s upbringing in France, her eventual deportation to Auschwitz-Birkenau, and how, in her seventies, she began to speak publicly about her wartime traumas. Much of the book is set during a 2020 school trip to Poland that was designed to introduce students to the horrors of the Holocaust. Kolinka’s role on the trip was as a survivor, there to speak to the students about her personal wartime experiences. Her co-authors, Morvan and Matet, joined the trip in order to document it for the graphic novel.

Readers who have deep familiarity with other Holocaust graphic novels will no doubt see vestiges of these other works in Adieu Birkenau. Using travel to Poland as a conduit for conveying historical traumas can be found in Jérémie Dres We Won’t Visit Auschwitz. Cesc and Efta’s superimposing contemporary experiences atop historical memories is also not novel; Rutu Modan did this in The Property. The use of history to inform reader reactions to contemporary injustices is also something that is present in other Holocaust graphic narratives. This includes Folman’s Where is Anne Frank and Sid Jacobson and Ernie Colón’s Anne Frank.

My point in calling attention to the employed narrative tropes and the artistic decisions made by Adieu Birkenau’s creative team is not to suggest that their work is a duplication of previously issued works. Nor is it to offer a comparison that concludes that one rendering of the Holocaust is preferable to another. Rather, acknowledging what has come before - and with regards to the Holocaust, it is so very much - allows for a greater appreciation for what is new and novel in Adieu Birkenau’s exploration of the Holocaust.

First is the audience of school children who attend the trip to Poland alongside Kolinka. Though we do not know much about them, what we do know is that they are not students who attend a Jewish day school. Rather, they are average French school children who are taking advantage of the opportunity to learn from someone who personally suffered during a traumatic moment in world history. In fact, they are quite like Kolinka was as a child: an average French citizen. Kolinka loved playing sports and her closest friends were not Jewish. In fact, she openly shares with the reader that her family was not particularly religious. By calling attention to the ways that Kolinka is like the children with whom she is travelling and not someone primarily defined by something that makes her other, they bear witness to a tragedy that could have befallen them had they been born at a different time and to a different family. As witnesses, they, too, become owners of a sacred story and become part of the narrative of transmission. As readers, we, too, now become owners alongside the children, bound by the same obligation.

A second important feature of the work is its depiction of bodies. Maus’ power lay in its metaphoric depictions that highlighted the ways that Jews (and other groups) were seen as distinct from one another. Cesc and Efa do the very opposite. Their illustrated bodies are drawn in proportion and reveal the realness of the human physique and what happens to it when it is broken down and ravaged by hunger, disease, and violence. Readers see what naked bodies of average women look like as they await having their heads shaved and their arms tattooed. This includes flabby midsections, sagging breasts, and pubic hair. Their rendition eschews a Hollywoodization that presents bodies in an unrealistically idealized form. Instead, once again, what readers see are real people and real victims. Furthermore, the illustrations capture the women trying to cover themselves as they are exposed against their will. I cannot recall another example of a Holocaust graphic novel that so boldly and graphically depicts the human form at its most vulnerable and with this, the brutality of the Nazi regime.

The primary creative license that Cesc and Efa take has to do with a series of dark shadows. Used in panels set in Birkenau, they inhabit Kolinka’s memories and represent the many Jews who were killed because of Nazi persecution. As Kolinka guides the students through Birkenau, the shadows become illustrated in the present and no longer solely occupy space in Kolinka’s memories. Their enduring presence in her memory results in them becoming imaginatively rendered in the present. In these scenes, readers come to better understand the awful staying power of trauma and how, despite having lived outside of Birkenau for over 70 years, parts of her remain there too.

It is the confluence of honest renderings of the past, depictions of the impact of trauma, and the invocation to create a different future that make Adieu Birkenau a valuable addition to the catalogue of Holocaust graphic novels. The children’s personal interactions with Kolinka at Birkenau depict the relationship that forms between the survivor who testifies and the audience who receives it. What we, as readers, gain from witnessing their transformation is the opportunity to also be transformed as we gain new understandings into one of the 20th century’s worst atrocities through the narrative power of a single survivor.