Miné Okubo’s Masterpiece: The Art of Citizen 13660. Los Angeles: Japanese American National Museum, August 28, 2021 -

February 20, 2022. <https://www.janm.org/exhibits/mine-okubo-masterpiece/>

Miné Okubo’s Masterpiece: The Art of Citizen 13660. Los Angeles: Japanese American National Museum, August 28, 2021 -

February 20, 2022. <https://www.janm.org/exhibits/mine-okubo-masterpiece/>

reviewed by Tony Wei Ling

The museum’s path is

a loop, and so a visit to JANM’s Citizen

13660 exhibit either begins or ends with a view into the same shambly

wooden structure: an original barracks removed and rebuilt from the Heart

Mountain concentration camp. Part of JANM’s ongoing exhibit on Japanese

American history, Common Ground, this

building-inside-a-building bookends the celebration of “Miné Okubo’s

Masterpiece.” Visitors first travel through Common

Ground’s rooms, which span the earliest waves of immigration through to

WWII incarceration and its aftermaths; the final room, situated just before the

entrance to the Okubo exhibit, covers the 1970s/80s political struggle for

redress that followed internment. Along with the architectural bookend of the

barracks, this history of the Redress Movement physically frames the museum’s

75th anniversary exhibit of Citizen 13660.

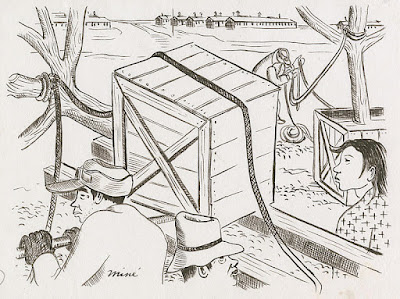

The

JANM exhibit is structured into a narrative of the book’s production,

displaying the variety of materials (varied camp sketches, original Citizen 13660 drawings, and page mockups

combining drawing, typed caption, and marginal edits) in a

compositional/editorial process of negotiated meaning. Miné Okubo’s iconic 1946

book pairs observational cartoons with terse first-person captions and follows

Okubo through multiple relocations and incarcerations between 1939 and 1944:

Berne to Berkeley, Tanforan to Topaz. By laying out the Citizen 13660 exhibit, room by room, into stages of drafting,

design, and correction, the exhibit opens up for interrogation the multiple

actors and influences that brought it into publication.

|

| Mine sleeping on a cot in her barrack |

| |

Such

an interrogation is important because Citizen

13660’s rendering of camp life’s “humor and pathos” has often been

preemptively read as a political act in itself, one that critiques the events

it charts and anticipates the organized call for reparations. No doubt much of

this reputation comes from the book’s use as testimony in the 1980s, during

which Okubo submitted her book to the Congressional Commission on Wartime

Relocation and Internment of Civilians as evidence of government wrongdoing.

However, scholars like Christine Hong warn against subsuming the book within

this “retroactive interpretive lens,” since doing so “arguably obscures more

than it illuminates Okubo’s legacy as a wartime artist.” Indeed, as Hong

reminds us, Citizen 13660 could only

have been published immediately following the war (and during the cross-country

dispersal of former incarcerees) with the support of the WRA officials who ran

the camps, some of whom endorsed the book. The book became, perversely, “an

affirmation of the democratic potential of the American concentration camp,”

Hong writes. This affirmation required fitting Okubo into the exemplar of an

“entirely American” Nisei character (to quote Pearl Buck), such that reviews of

her book sounded almost identical to the artist’s truly wild character

references, such as the one from her teacher Glenn Wessels describing her as

“un-Japanese in sympathies and in manner of thought.”

Citizen 13660’s legacy has continued to

work through this exemplar form, making Okubo into an ethnic representative

whose witnessing and recording of the camps always already testifies to one

political end or another: either a distinctly American story that mines the

everyday adjustments and discomforts of camp life for common ground with white

readers, or a sharply critical, irony-laden statement of racial protest.

Debates about how best to interpret “Miné Okubo’s Masterpiece” as a politically

potent (though not obvious) artistic work are not about pinning down the

precise political character of a single cultural figure: they are about

dislodging both the book and the artist from the position of exemplar. Hong’s

caution not to read Citizen 13660 through

a single lens clarifies the pressures of exemplarity as a representational

mode, which can attempt to redeem ambiguous or close-mouthed texts by forcing

them to speak.

Although

the museum’s physical layout leads the visitor straight from redress to Okubo,

JANM seems to follow Hong’s caution not to enclose the artist within the

political lens of redress. The curatorial writings about the exhibit are

relatively circumspect on Okubo’s politics; they describe the book as

“groundbreaking” for being “the first book-length account on America’s

concentration camp from the perspective of a former incarceree” and “an early

example of a graphic memoir,” not for being a self-evident critique of the

state.

|

| Memorial service for James Wakasa |

Perhaps

more importantly, the exhibit’s design draws the visitor’s attention to edits

made to both Okubo’s text and drawings, asking the visitor to compare versions

of the same page. One key moment in the exhibit places a page from the final

book next to its draft page mockup: it’s the page in which Okubo addresses a

guard’s fatal shooting of an “elderly resident.” The final version’s caption

consists of a single paragraph, from which much of the draft page’s typewritten

details have been cut. Ironically, one of the remaining lines in the published

version reads: “Particulars and facts of the matter were never satisfactorily

disclosed to the residents.”

|

| Detention room filled with departing residents |

What did it mean to excise those

slight elaborations on “the Wakasa case” from the final publication? And what

can readers today make of such an elision, in this already famously elliptical

work? Against the backdrop of its various political mobilizations

(re-domesticating alienized incarcerees, testifying towards redress), Citizen 13660 might be best

characterized by its oscillations and reticence––qualities that JANM’s exhibit

faithfully reflects and interrogates through its attention to revision and

editorial process. JANM’s Education Unit has designed a wonderful activity

guide that asks visitors to participate in slow examination of Okubo’s drawings

through activities in “close looking,” comparison between early sketches and

final versions, and even invitations to draw one’s own illustrations from

Okubo’s captions.

Over

the decades, Citizen 13660 has been

made a representative of multiple political/racial narratives––narratives not

obviously cosigned or directly produced by the work itself. These interpretive

frames are partly external impositions on the book, but they are also generated

in large part by the work’s odd combination of documentation and reticence. A

strategy of “documentation through reticence,” in fact, might be fitting to

stress the scientist’s objectivity in Okubo’s textual voice. Or maybe

“reticence through documentation”: the book rattles off a steady rhythm of

particulars to fill incarceration’s empty time. “You had to work hard to keep

yourself going, and to keep from thinking,” Okubo said in a post-publication

interview. And as Greg Robinson observes, “Okubo may not have been referring

simply to her camp experience,” but to the stifling representational burden of

Americanizing/humanizing incarcerees.

|

| Landscaping with trees |

Another

way of looking at Okubo's reticence is as a strategy of abstraction––as a

stylistic register that responds to the pressures of racial exemplarity.

Talking about Citizen 13660 in terms

of abstraction may seem odd, given the work’s obvious claims to figurative

representation (as documentary) and its obsessive interest in particulars:

barrack and room numbers, curfew times, toilet arrangements, wages. Its text

and image move at different paces, though, and rather than elaborating or

contextualizing the moments depicted in each drawing, Okubo’s captions often

direct the reader and characters onward, onward, onward, at a brusque pace

something like a punchline.

“Everyone was building furniture and fixing up

barracks and stalls. Many of the discomforts of the camp were forgotten in this

activity.”

“Letters from my European friends told me how

lucky I was to be free and safe at home.”

“The incomplete partitions in the stalls and

the barracks made a single symphony of yours and your neighbors’ loves, hates,

and joys. One had to get used to snores, baby-crying, family troubles, and even

to the jitterbugs.”

Her drawings, by

contrast, loop the eye into compositions that Hong describes as “[w]himsically

Matryoshka-like in visual architecture,” with figures whose gaze and movement

rarely advance in a single direction––and which almost never resolve into any

legible kind of effect. Okubo

threads her readers between progressive and melancholic time: we neither move

briskly into the future (as the book’s final caption seems to promise), nor do

we stay endlessly in some fractured, traumatic moment.

In

his essay on abstract comics, Jan Baetens introduces the idea of abstraction at

the level of sequence rather than just the individual image. Abstraction as a

sequential strategy can serve narrative ends by “foreground[ing] an enigma” and

by withholding connections between image-moments, although in Baeten’s model,

abstraction and narrative are always in “active conflict.” Abstraction in

Okubo’s proto-”graphic memoir” doesn’t mean a total absence of either

figuration or narrative; I mean something like a looseness between forms and

what those forms legibly, identifiably signify. Not a lack (of particulars, of

lines, of images), but a loose connection: resemblance under reconstruction;

narrative in double vision.

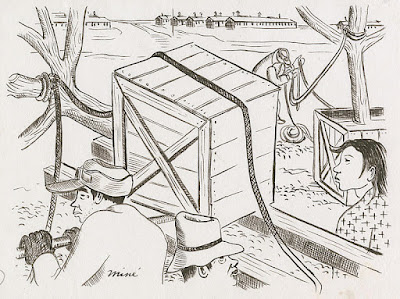

|

| Sewage system repairs |

At the level of image, Okubo works

out a visual shorthand for Japanese faces that refuses the specificity of

portraiture, favoring instead a semi-opaque, semi-abstracted cartoon style that

consciously both resembles and revises the racial caricature Okubo saw in

comics. At the level of narrative, Okubo’s temporal “mixed

messages” loosen the hold of progressive time, which preferred to frame

internment as a momentary lapse, and which hoped to smoothly re-domesticate its

internal aliens through their post-camp dispersal. Her layered and

contradictory sense of time rehearses internment’s own absurd and distorted

relationship to linear temporality; the minor but multiple incongruities

between captions and drawings eat away at the narrative sense a reader attempts

to make out of panels, pages, incidents, particulars. For both the singular and

sequential registers of representation, abstraction emerges as a way of managing expectations:

meeting the narrative demands of reinstated citizenship and yet clearing room

for alternate narrative connections.

As

some early book reviews, displayed in the exhibit’s final room, were keen to

observe, Okubo skirts obvious caricature or anguish in favor of “tolerance and

restraint.” Her few moments of straightforward outrage are all that keeps the

book from being “inhumanly quiet,” one reader said. These reviews seem to sense

irony where they expected feeling (ironized state critique would later become

the conventional reading), but they largely emphasized––and admired––the book’s

apparent lack of bitterness. Of the reviews on display at JANM, one even offers

Citizen 13660’s “touches of humor” as

proof that Okubo “rises above resentment and rancor.” The relief is palpable

amid the slight confusion.

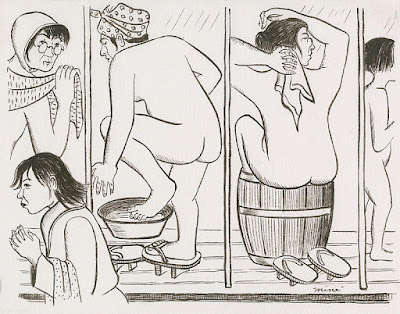

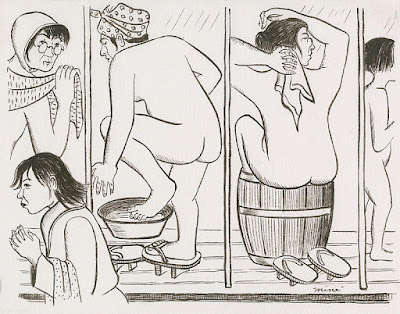

|

| Bathing in tubs |

Not

on display (but relevant here) is a 1947 review by Setsuko Matsunaga Nishi, a

sociologist who was incarcerated at Santa Anita during the war. Nishi also

notes the book’s “commendable objectivity,” but she complains that among these

precisely observed discomforts of the camps, what “is not evident to most

readers is the disillusioning torment that evacuation meant to them.” Nishi, of

course, was right: Citizen 13660 refrains

from foregrounding tragedy. And perhaps most readers were happy to read the

book as a funny and humanizing, if oddly reserved, account of a nation’s

embarrassing lapse. Citizen 13660 did

on one hand facilitate the human empathy and “common ground” upon which a

progressive American time could be plotted. Yet it also dealt closely and

actively with the very logic of racial identification and exemplarity that has

followed the book through its initial period of publication and its Redress-era

resurgence. In its very title, Citizen

13660’s abstracted identification with/of Okubo brings some irony to the

close association reviewers made between the artist and her representational

strategies of restraint, humor, and (apparently) forgiveness. Citizenship,

already an abstract form of legal personhood, becomes one half of an oxymoronic

identification.

One of Nishi’s more

disparaging remarks describes “the very facile nature of the book” as being in

conflict with the “deep subjective meaning” of the art. “If the reader were to

verbalize the significance of some of the illustrations,” she writes, “he might

be surprised at the bitter irony.” What these drawings signify––what they are

pictures of, exactly––is not immediately

clear or stable. There’s no way to resolve its rhetorical shape into either a

1980s voice of oppositional critique or the 1940s one of redemptive propaganda.

What looks from one angle like redacted/repressed tragedy looks from another

like “good humor” (a particularly oblique and unfixed mode of historical

relation) and from yet another like “bitter irony,” to use Nishi’s phrase.

Okubo’s reworking of figuration and narrative sequence, which I’ve identified

as a semi-abstracted style, disorient and disperse anything more than a bare

sense of narrative facts and feeling. Katherine Stanutz describes this effect as an inscrutability open to

future reinscription––“what is ungrievable in 1946 gradually becomes grievable

in the 1970s and 1980s”––but to me, the lightness of Okubo’s text reads not as

a deferral of grief, but as grief’s less hallowed (and less legible) form.

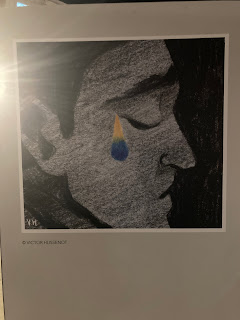

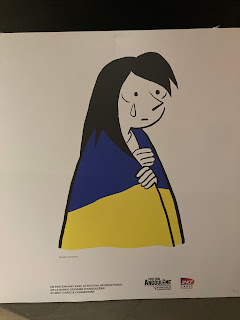

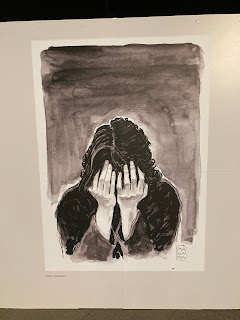

Near

the entrance to the exhibit, three expressive charcoal drawings from Okubo’s

camp era-corpus hang on display––all of them done at a much higher and more

recognizably “fine arts” register of abstraction. In one, a gaunt, childlike

figure presses its face and hands against the picture plane; in another, an

adult and a child peer crookedly out through barbed wire that divides the picture

into multiple, pronged horizons. The crosses used to denote the barbs are

integrated into the figures’ furrowed brows. These emotive drawings are

especially instructive context for the cartoon style she chose for Citizen 13660, which is stiffer, cooler,

and more line-driven in its mark-making. Like the charcoal drawings, Citizen 13660’s illustrations still

flatten the depth of field, emphasizing the compressed dimensions of the page

over that of three-dimensional space, but its characters rarely bear the same

expressions of outright anguish, nor do they look directly out at the reader.

Instead, the figures of Citizen 13660

are almost always engaged in a gesture of work, of adjustment. Even rest

becomes just another task that passes time.

You

can’t, as of this writing, visit the Okubo exhibit in person––JANM is

temporarily closed due to the rise in COVID-19 cases here in the US.* But JANM’s

digital collections host a rich archive to explore, including Okubo’s

drawings as well as many other collections, and the museum is hosting a series

of online events/workshops related to the Citizen 13660 exhibit. I’m grateful to

their work in putting together all of these routes into Miné Okubo’s work,

which still has so much to teach us.

A version of this review will appear in the print edition of IJOCA.

*The museum will reopen on February 1, according to a staff member.