The Ninth Art at the Centre Georges Pompidou:

A Review of Comics 1964-2024

Mark David Nevins

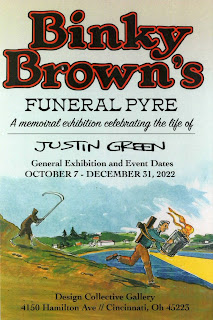

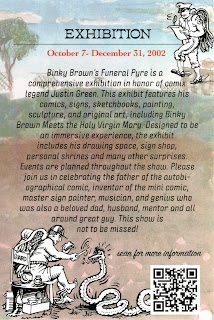

Fig. 1

One could say that comics and art museums have had an uneasy relationship--but the reality is, they’ve mostly had no relationship at all.

One of the first large-scale attempts to bring comic art into museums in a serious way was MoMA’s 1990 show “High/Low: Modern Art and Popular Culture.” This ballyhooed exhibition aimed to show how pop culture shapes “high” art, juxtaposing fine artists, such as Picasso, Warhol, and Lichtenstein, with comic strips and newspaper ads--some of which had served as sources or “swipes” for those artists’ work. From scholars to fans, reception was scathing. Roberta Smith famously sneered in The New York Times that it was “at best, the wrong exhibition in the wrong place at the wrong time.”1

Me? I didn’t really care. I was 25, completely unconcerned about esoteric intellectual debates, and awestruck to be able to spend hours looking at “Krazy Kat” original pages.

A less intellectually encumbered celebration of comic art came 15 years later with “Masters of American Comics,” which was shown across two venues in Los Angeles: the Hammer Museum and MOCA. This 2005 show highlighted 15 comics “masters”--from Winsor McCay and George Herriman to Jack Kirby, Art Spiegelman, and Chris Ware--with each essentially given his own mini-retrospective. A sprawling “greatest hits” of American comic art, the show was praised for its attempt to legitimize comic art as museum-worthy while faulted for presenting a canon that was, without exception, white and male. (Even early in the 21st Century, Herriman was still “passing,” posthumously.)

Unlike “High/Low,” the “Masters” show presented some problems for me--40 years old and in possession of a Ph.D. in Literature--due to its lack of any curatorial framework or “idea” behind the exhibit: no examination of commercial or cultural contexts; no argument for the development of an art form; no attention to the various marginalizations that had shaped the medium of comics. That said, I left my pretensions at the door to bask in the glow of hundreds of pages of original art--and left with some insights that still inform my passions and opinions to this day: Frank King and Milton Caniff are absolute geniuses; Lyonel Feininger is criminally underrated, while Will Eisner is a bit overrated (sorry); and Winsor McCay’s work really must be seen in color to be fully appreciated--the black-and-white original art mostly sits on the wall and disappears.

This past year, nearly two decades later, France raised the stakes with a compendious and ambitious exhibition at the Centre Pompidou titled “Comics 1964-2024,” curated by Anne Lemonnier, Emmanuèle Payen, Thierry Groensteen, and Lucas Hureau.2 Billed as a celebration of 60 years of le neuvième art (“the ninth art,” a term adopted in the 1960s by Francophone critics seeking to legitimize comics), the show gathered hundreds of works from around the globe and across a remarkable range of styles, formats, and movements. This was not the Pompidou’s first foray into comics: previous exhibitions included shows in the 1970s and 1980s on comics and everyday life and comics from the 1950s, as well as a blockbuster Hergé show in 2006. But “Comics 1964-2024” has been by far the most ambitious European effort to present comics holistically as a mature art form.

Thanks to some serendipitous business travel, I was lucky enough to have a free day in Paris on literally the last day of the Pompidou show, thus giving me a trifecta of the most important museum shows about comics in my lifetime … so far.3 I stayed inside the museum for the entirety of its opening hours on Sunday, Nov. 3, 2024, exhausting the friends who had joined me--and I could easily have spent three or four more days at the show without getting bored. Indeed, surrounded by more than 1,000 comic pages, covers, illustrations, sketchbooks, printed books, and other ephemera, I’d have happily been locked into the museum for a week!

After passing through a “portal”--an homage to the 20th-Century master Jean-Claude Forest by beloved and prolific 21st-Century cartoonist Blutch--the visitor entered an initial room that presented a powerful argument: the global upheavals of the 1960s--cultural, social, political, and artistic--had catalyzed a new kind of comic art.

Fig. 2

Or, perhaps put more daringly: catalyzed by those events, comics as a form had become something completely different from its historical roles as children’s entertainment or an occasional diversion for adults in daily newspapers.

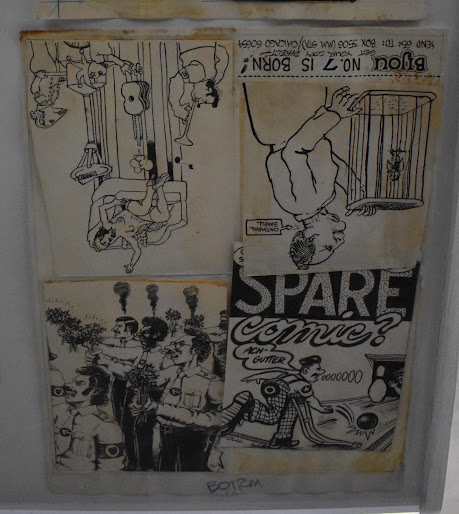

As linguists and anthropologists talk about polygenesis, there was something going on in the zeitgeist or collective unconscious during this decade that sprouted distinct but essentially related sequential narrative traditions. In France, a touchstone was the rise of Hara-Kiri, a self-proclaimed “stupid and nasty” magazine featuring bandes dessinées mocking bourgeois politics and aesthetics. In Japan, Garo magazine presented a showcase for introspective, radical manga for adult readers. And in the United States, the Underground Comix movement exploded with Robert Crumb, Justin Green, Trina Robbins, and other over-the-counter pioneers who irreverently satirized mainstream American culture and mores.

That opening salvo for “Comics 1964-2024” was strong: the claim that these simultaneous cultural eruptions laid the foundation for what was to come in sequential art over the next half-century. Just a few decades later, the world would witness the almost unimaginable flowering and maturation of the graphic novel, the literary comic, and the hybrid artistic experiments that represent comics as a medium and an art form in the 21st Century. From origins at the margins of proper society--countercultural ’zines, head shops, underground presses--comics have evolved into a medium now worthy of being presented in one of the most admired museums in the world.

For better or worse, that opening argument dissipated as one got deeper into the show. As the exhibit unfolded, the programming shifted to a loosely structured sequence of theme-based rooms, seemingly committed to displaying a “greatest hits” of stunning comic art rather than exploring any cohesive story about the medium’s development. For visitors newer to comics, the sheer variety must have been thrilling--if perhaps overwhelming--but for those with more knowledge of comics’ history, its major works and key creators, the lack of historical or conceptual throughline was frustrating. Or that was certainly my own feeling, as well as the report I heard from more than a few knowledgeable friends lucky enough to see the show.

With “Contre-culture” (Counterculture) as the first room, the themes of the following rooms ranged from “Fiction du future” (Future Fiction or science fiction) and “Rêve” (Dreams) to “Villes” (Cities) and “Géométrie” (Geometry). This selection of themes felt arbitrary--if not uninteresting. While the whole exhibition gave the attentive viewer both visual delight and historical range, it came at the expense of clear intentionality and without much curatorial apparatus.

The early countercultural material was rich with context and layered juxtaposition. Seeing French underground comics alongside American and Japanese works from the same era revealed not just parallel energies but fundamentally different--and even orthogonal--artistic responses to the global cultural moment. Where American underground comix leaned into psychedelia, drugs, and sexual liberation, French artists channeled their energy into political dissent and aesthetic innovation, as in the case of Forest’s Barbarella or Peellaert’s Jodelle. Japan’s Garo offered yet another track: class struggle, existential introspection, and artistic minimalism, perhaps taking cues from contemporary national writers and filmmakers, such as Kenzaburō Ōe and Nagisa Oshima. This juxtaposition was brilliantly instructive--as the wall text explained:

The 1960s saw the development of forms of free expression and protest all over the world, going against the values and hierarchies of establishment culture. This counterculture was the identity marker of a generation and especially permeated the field of comics, which until then were considered as being for children by their very nature.

Fig. 3

In France, Japan, and then the United States, new forms of comics appeared on the fringes of mainstream production. They expanded comic readership and sowed the seeds for themes that would take on considerable significance around the turn of the century, defining the contours of modern comics: graphic journalism, confessional style, addressing major societal issues, and mixing comics with other forms of art. The 1960s also marked the start of the process of cultural legitimisation that would lead to the recognition of “the ninth art.”

![]()

![]() But, as the

exhibition unfolded, its themes became more diffuse. “Rire,” the room

dedicated to humor, gathered pages by Claire Bretécher, André Franquin, Bill

Watterson, and Albert Uderzo, among others--but presented them with no logic or

framing. Which caused the viewer (or me, at least) to start a little mental

game: “Which creators should or could

have been included in this room, and why were they omitted?” As I proceeded

through the rest of the exhibition, that game took up more and more of my

mental attention. In the section on “black and white,” for example, to illustrate

how comics intersect with film and roman noir, I’d have preferred less

Frank Miller (who has always struck me as overly derivative of his forebears)

and more Jose Muñoz (Fig. 4), Baru, Didier Comes, Alex Toth, or even

Darwyn Cooke’s masterful interpretations of Richard Stark’s brilliant series of

hardboiled novels about a thief named Parker.

But, as the

exhibition unfolded, its themes became more diffuse. “Rire,” the room

dedicated to humor, gathered pages by Claire Bretécher, André Franquin, Bill

Watterson, and Albert Uderzo, among others--but presented them with no logic or

framing. Which caused the viewer (or me, at least) to start a little mental

game: “Which creators should or could

have been included in this room, and why were they omitted?” As I proceeded

through the rest of the exhibition, that game took up more and more of my

mental attention. In the section on “black and white,” for example, to illustrate

how comics intersect with film and roman noir, I’d have preferred less

Frank Miller (who has always struck me as overly derivative of his forebears)

and more Jose Muñoz (Fig. 4), Baru, Didier Comes, Alex Toth, or even

Darwyn Cooke’s masterful interpretations of Richard Stark’s brilliant series of

hardboiled novels about a thief named Parker.

Fig. 4

To continue, while hopefully not complaining overmuch, the 1980s “realistic” branch of Franco-Belgian comics, not so fashionable these days, was completely overlooked (no Jean Giraud, no François Boucq, no Hermann), as was much of the kids’ section (no Peyo, no Quino). While that first room had implicitly set the show’s parameters as Western Europe, Japan, and North America, the utter omission of comics from Africa (with strong traditions in South Africa, West Africa, Nigeria, and Algeria); China, Korea, or the rest of Asia outside Japan; or South America (aside from the few creators published in Europe like Muñoz and Alberto Breccia) was puzzling. The United Kingdom also got short shrift. The omission of inarguable giants and massive influencers like Jaime and Beto Hernandez (USA), Max (Spain), Joost Swarte (Netherlands), and Dylan Horrocks (New Zealand) was mystifying. And there not even a glimpse of the Italian Milo Manara, one of the biggest names in latter-day European comics--though perhaps for an all-ages show a 13th room on Erotica was understandably vetoed.4

While the European curators made efforts to include plenty of North American cartoonists, their perception of 21st-Century work from the new world felt dated. Creators, such as Eleanor Davis, Sammy Harkham, Dash Shaw, or Jillian Tamaki, could have settled nicely into more than one of the thematic rooms and offered a more contemporary look at how comics creators across the Atlantic are engaging with the form. What’s been happening in English-language comics in the latest generation is as exciting as anything coming from the continent, but you wouldn’t know it from this show.

One side note on the exhibition’s physical space: clearly the desire to show as much original comic art as possible was paramount. But each room--even the makeshift ones set off by curtains--felt cramped and claustrophobic, especially with the masses of enthusiastic crowds. Artwork was hung tightly arranged, with little breathing room for the material or the viewers. The original works were mostly presented simply--often without frames at all--but the density, along with the lack of commentary, again made it difficult to discern patterns or threads, never mind arguments. One could happily lose hours in any room, nose inches from stunning originals--seeing the actual ink on paper in the hand of the artist is transporting--but the exercise felt more like rummaging through some lucky collector’s trove than engaging in a museum show.

A section on horror or fear, “Effroi,” followed suit. With work from the EC Comics of the 1950s (which, it should be noted fall well outside of the show’s stated timeframe!), Japanese masters Junji Ito and Hideshi Hino (Fig. 5), and Charles Burns, it was packed with macabre brilliance but, again, no curatorial logic. Horror is not a monolithic genre--it spans the grotesque, the psychological, the physiological, the absurd, and more--and without guidance, the viewer was left to make sense of jumps from, say, Swamp Thing to Daniel Clowes without much sense of relation. That said, highlights abounded, including 110 pages from Hino’s Hell Baby, which held my attention for a good half hour. Oddly, the curators offered a full wall of the spellbinding work of the German master, Anke Feuchtenberger, in this section, where it felt out of place. Perhaps “Dreams” would have been more suitable.

Fig. 5

To be fair, every section of the exhibit pleased, once the viewer gave up looking for a curatorial argument and simply enjoyed the work. “Rêve,” the room on dreams, included some of the most imaginative work on display--from Fred’s surreal Philémon strips to Julie Doucet’s dream diaries to David B.’s Les Incidents de la nuit (Nocturnal Conspiracies).

In this area, an oneiric anthology, comics’ unique power to blur inner and outer worlds was on full display. A towering installation, perhaps ten feet tall, of the first 32 pages of “Les Cauchemars de l’amateur” (Fig. 6), a never-published nightmare comics story by Killoffer, was one the highlights of this section, and indeed the entire show. (How is it possible that this work has never been collected into a book?!)

Fig. 6

Another triumph was the room dedicated to “Couleur,” which traced how artists from Moebius to Brecht Evens use color not just decoratively but narratively and emotionally. Seeing original pages from the illustrator/cartoonist Lorenzo Mattotti (Fig. 7), Nicole Claveloux’s The Green Hand, and Moebius’s ground-breaking Arzach (Fig. 8) in their unmediated, physical form offered a rare treat: mechanical printing simply cannot capture the nuance of these richly painted colors.

Fig. 7 Fig. 8

Autobiography (Récits personnels) was a particularly strong section. Works by David B., Alison Bechdel, Fabrice Neaud, and Dominique Goblet, illustrated how comics can be a powerful medium for emotional intimacy, psychological inquiry, and self-reinvention. The juxtaposition of Bechdel’s Fun Home and Neaud’s diary comics underscored how different cultural contexts may shape confessional storytelling--even in what some viewers might (falsely) assume would be a leveling category such as queer comics. But again, the lack of a curatorial thesis led to puzzling omissions and lost teaching moments. It’s no surprise, of course, that this section was so strong, since autobiography has in many ways been the foundational mode for comics’ self-reinvention since the 1990s. As such, autobiography isn’t just a one category among others--it is, arguably, one of the central evolutions of comics in the last 30 years, and that argument could and should have been made.

The section, “Histoire et mémoire,” powerfully elucidated comics’ relationship with history and memory. Pages from Art Spiegelman’s Maus, Keiji Nakazawa’s Barefoot Gen (Hadashi no Gen), Emmanuel Guibert’s La guerre d’Alain (Alan’s War, Fig. 9) and Jacques Tardi’s World War I narratives (Fig. 10) traced how cartoonists have tackled historical trauma with depth, immediacy, and moral urgency. These works stand not only as documentation, but as emotional interpretation--and they remind us how comics, through juxtaposition and layering, are uniquely suited to convey the fragmented nature of recollection. However, since war comics have been such a dominant genre over the last half-century, including in the mainstream, a savvy viewer was likely awkwardly reminded of how much was left out.

Fig. 9 Fig. 10

To my dismay as an English Ph.D., the “Littérature” room felt the least essential. It presented capable adaptations of works by Poe, de Maupassant, Flaubert, and Steinbeck--alongside satirical appropriations, such as Winshluss’s Pinocchio and Posy Simmonds’s Gemma Bovery--but didn’t offer much insight or commentary into anything novel such adaptations might produce. Hunt Emerson’s sly and sometimes scandalous retellings of classics, such as Lady Chatterley’s Lover and The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, would have been much more illuminating, not to mention David Hughes’s magnificent Othello. (Both artists are British.) While there’s nothing wrong with showing comics’ engagement with literature, the underlying message here seemed to be one of validation: “Look, comics can do literature too!” Yet the deeper truth--that comics can do many things that traditional words-only prose cannot--was left unexplored. The section missed an opportunity to explain the medium’s distinctive capabilities: its ability to collapse time, blend narration and image, and structure perception spatially as well as temporally.

By the final few rooms--which focused on geometry, cities, and formal experimentation--the show began to feel more like a sprawling cabinet of magnificent curiosities than a presentation of ideas organizing the displays. I suspect most viewers, whether comics experts or casual visitors, were running out of gas by this point--yet perhaps they might not have been, had there been a clearer explanatory thread or conceptual map running through the exhibit. Indeed, the back end of the show featured some of the most visually inventive objects on display--including pages by Chris Ware, Jochen Gerner, Yuichi Yokoyama, and Marc-Antoine Mathieu--which dazzle in their conceptual complexity. Seth’s surprisingly large and meticulous model of his imagined city of Dominion (Fig. 11) was stunning, but must have been lost on some visitors who had by now reached complete cognitive saturation.

Fig. 11

For all its bounteous riches, I admit that “Comics 1964-2024” nevertheless left me with the feeling of a missed opportunity. The show began with a sharp idea: that comics around the world had collectively responded in a unique and unexpected way to the shocks and possibilities of the 1960s and have since matured into a complex, global, and increasingly popular set of languages and media--no longer an overlooked little sibling to more serious modes of high art. That idea could have carried through the exhibition, but, instead, the show followed a more traditional retrospective model: gather as much great work as possible and organize it loosely by theme. The result was often stunning--but rarely instructive.

However, being more generous, perhaps the exhibition’s biggest flaw--its lack of sustained argument--was also, for some viewers, its strength. Over glasses of wine after the show, one of my companions said to me, “I don’t know a lot about comics, but moving from room to room what was most amazing to me was how very different all of the work of the different creators is and what a vast universe of ideas and styles and subject comics can embrace.” No, the show did not lay out a coherent history or thesis, but it certainly conveyed comics’ astounding depth and breadth. And it did so with affection, admiration, and an earnest desire to elevate the medium.

So, a positive and optimistic conclusion. It was absolutely thrilling to see almost the entirety of a major art museum, like the Pompidou, turned over to comic art for the better part of a year, and “Comics 1964-2024” is truly unprecedented in its scope, depth, and sheer celebration. As comics continue to gain cultural legitimacy, we can hope that exhibitions like “Comics 1964-2024” may become more common. The Pompidou show may not have achieved the full integration of narrative and form, of ideas and images, that the best comics themselves offer--but it did bring graphic narrative into the halls of one of the world’s great museums, with no need of a Trojan Horse like “High/Low,” and put its diversity on display for a wide public. That alone is an achievement. The Ninth Art, like the curators who care for it, is still evolving. May the next major comics exhibition be even more beautiful--and a bit braver in its storytelling.

Endnotes

1 “High and Low Culture Meet on a One-Way Street.” The New York Times. Oct. 5, 1990.

2 It should be noted that “Comics 1964-2024” was just one part of a broader program at the Pompidou, “La BD à tous les étages” (Comics on Every Floor), which ran from May 29 to Nov. 4 of 2024. In addition to a series of lectures and performances, ancillary exhibitions included Corto Maltese: Une vie romanesque, focused on Hugo Pratt’s iconic sailor; “Tenir tête,” an immersive installation for children designed by the remarkable Marion Fayolle; a showcase of the avant-garde comics from the magazine Lagon; and “La bande dessinée au Musée” or “Comics at the Museum.” I was able to spend some time at this last show as well, which paired contemporary comics artwork with masterpieces of modern art. While I liked the concept, the promised “dialogues” didn’t really impress.

3 For those less lucky, a sumptuous catalogue was produced for “Comics 1964-2024.” Like the catalogues for the two earlier American shows, it deserves to be in the library of any committed comics aficionado.

4 On the other hand, another great Italian comics artist known for his erotica, Guido Crepax, was included. And rightfully so: once you get past the kink, Crepax is one of the most innovative and influential masters of page composition in all of comics history.

Mark David Nevins is a professor at Holy Cross College and heads a consulting group.