reviewed by Matthew Teutsch, Associate Professor, Piedmont University

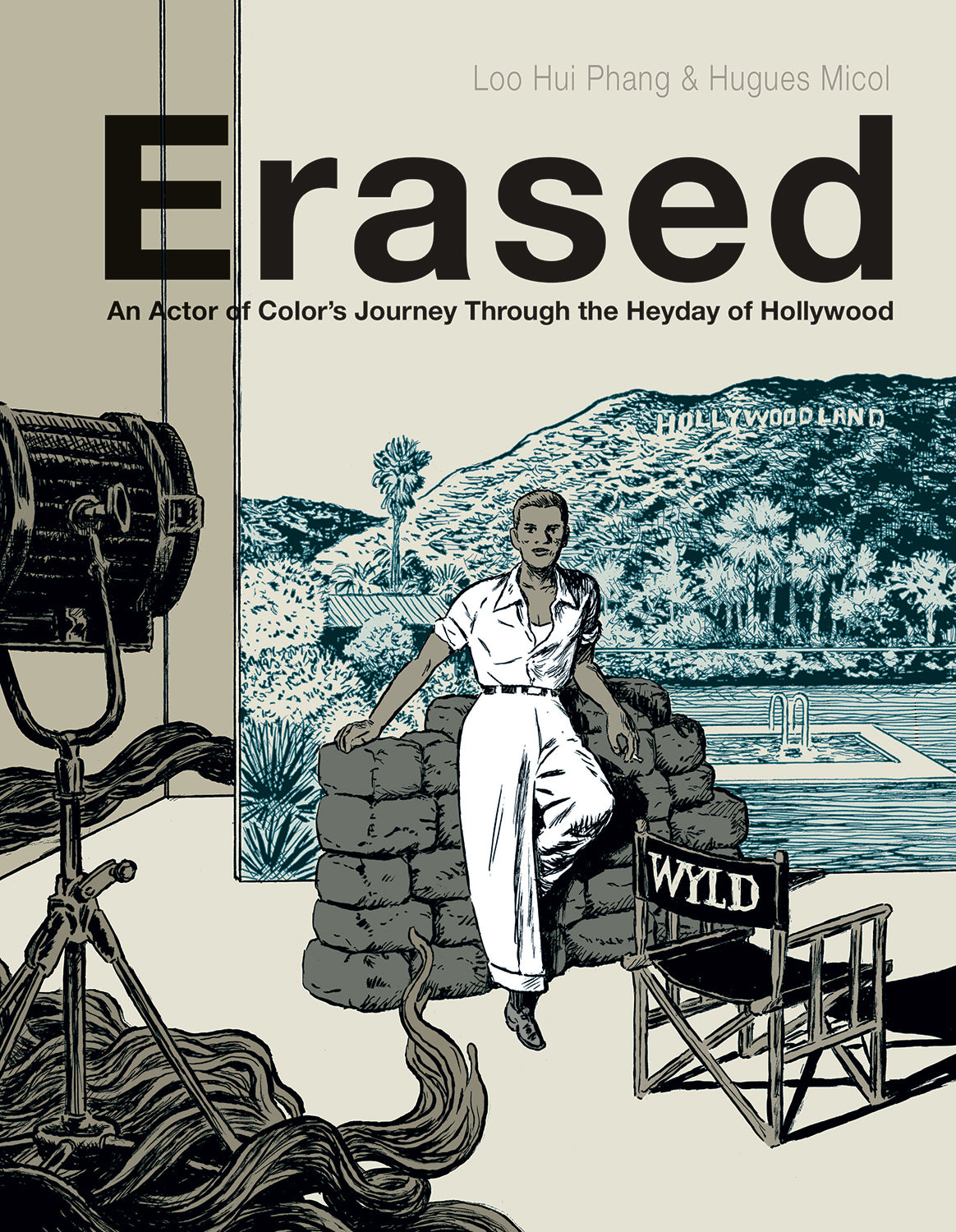

Loo Hui Phang and Hugues Micol. Erased: An Actor of Color’s Journey Through the Heyday of Hollywood. New York: NBM Publishing, 2024. 200 pp. US $24.99 (Hardcover). ISBN: 978-1-6811-2338-7. https://nbmpub.com/products/erased

Who was Maximus Ohanzee Wildhorse, an “actor with a thousand faces”? Why, decades after his heyday in some of the biggest films of the 20th Century, from “Gone With the Wind” to “The Maltese Falcon” to “Vertigo” and beyond, do we not know about Wyld’s legacy during some of the most important moments in cinematic history and in the history of the United States and the world? Loo Hui Phang and Hugues Micol’s Erased: An Actor of Color’s Journey Through the Heyday of Hollywood seeks to rectify the fact that Wyld’s work, once the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) deemed him a Communist, because he went to Kyrgyzstan in 1955 to portray Genghis Khan in a film by Aktan Okeev, vanished from the studio vaults. As a result of the HUAC investigation, film studios blacklisted Wyld, and “to safeguard the integrity of their back catalog and contribute patriotically to the Cold War effort, studios decreed radical edits,” essentially erasing Wyld from the annals of cinematic history.

In the afterword, Lelan Cheuk notes that as he read Erased, he placed Maximus “alongside Anna May Wong, Paul Robeson, Lena Horne, James Hong, and countless other talented performers relegated to a career of supporting roles drenched in racial stereotypes.” Because of his Black, Chinese, and Indigenous ancestry, Maximus could veritably play any “ethnic” role on screen, portraying enslaved individuals, Indigenous chiefs, Mexican revolutionaries, Oriental dandies, and more. Yet, with all of the promises from Louis B. Mayer to make Maximus the first Black star to be at MGM, telling him again and again that he planned to have Maximus star in a film adaptation of Othello that never materialized.

While Erased resurrects Maximus from the depths of oblivion, it also serves as a commentary on the role that celluloid images have on our culture, and the ways that cinema allows us to escape reality, but also informs our reality. After Cary Grant “discovers” Maximus in a gym, we see Maximus in a theater watching a western with Father Magnani. Micol’s first panel shows a white cowboy chasing two Indigenous warriors as he shoots at them. In the foreground, we see a boy’s fist raised in the air as he yells, “Yippee! Whip’em good, redskins!” Father Magnani tells the boy to settle down and reminds him, “it’s just a movie.” Maximus pushes back, telling the priest that what they see on the screen is not just a movie, and that when he watches the action, he “want[s] to be a cowboy, not an Indian.” This feeling is what Franz Fanon and James Baldwin write about in relation to seeing oneself on screen as the “savage” or the “uncivilized,” and thus rooting for the white hero. Baldwin writes, “It comes as a great shock to see Gary Cooper killing off the Indians, and although you are rooting for Gary Cooper, that the Indians are you.”

Father Magnani tells Maximus that images and narrative have power and that, “[t]he cinema is but an adaptable tool.... It can be made to serve any ideology.” Still looking at the screen, Maximus replies, “Me, I just want the Indians to win.” Maximus takes Father Magnani’s advice, and he imbues his acting, specifically after the initiation of the Hays Code in 1934, with subtle gestures and signs that subvert the code. As well, he incorporated gestures and wardrobe choices to convey “secret messages,” such as references to African roots, Toussaint L’Ouverture’s initials in a movement, a raised fist in defiance, and more.

While the dialogue and textual narrative convey the illusion of cinema and Hollywood, Micol’s surrealist illustrations, which bring to mind the work of Bryan Talbot’s work in Armed with Madness: The Surreal Leonora Carrington, work with Phang’s text to create an uneasy feeling of reality. Erased opens with seven out of the first eight pages being full-sized illustrations without panels. The opening page depicts a masked figure walking in the desert amidst images of various characters that Maximus plays throughout his career. These characters are ensconced as parts of a cactus, as bearing the weight of the scene, and as traversing the landscape as the narrator begins, “Hollywood is fiction, and like all fictions, it is myriad, changing, sincere, deceitful and unbridled engine of predatory fluidity.” It changes and morphs, relaying ideologies, as Father Magnani puts it. The next page continues to follow the masked figure as an eagle snatches the individual up in its claws, depositing the person into a seemingly bottomless cavern that reveals itself, on the third page, to be a woman’s head. Thus, the malleable, masked thespian becomes part and parcel of the audience member’s consciousness. The narrator reiterates, “Hollywood is a fiction. It feeds on stories. Manufactures heroes. Celebrates them. Torches them.” These “heroes” all become part of us as audience members, and the masked person, as they fall into the black hole of the woman’s hair, gets lost to the march of time, becoming one of the torched heroes.

When Maximus faces HUAC about his involvement with Okeev’s “Genghis Khan,” they torch him, turning him from a celebrated hero to a mere shadow haunting the edge of the frame. Micol’s depiction of this moment harkens back to the opening, placing the masked individual on a pyre, surrounded by burning film reels as the flames lick at the flesh while the head of a bald eagle stares at the audience in the lower right corner from behind the lynching. The image symbolically depicts Maximus’ erasure from the annals of cinematic history, burned alive by the very film reels that he made popular. The studios sought to protect themselves from HUAC, and “Maximus Wyld became an evil infecting Hollywood--one it was urgent to eradicate.”

Erased, at its core, does more than just resurrect Maximus Wyld’s career. Through the narrative and illustrations, it highlights the myths we tell and the ways that those myths, depicted on larger-than-life screens, impact our very beings. It dives into the illusion, even with actresses, such as Margarita Carmen Cansino (Rita Hayworth) and Julian Jean Turner (Lana Turner), that Hollywood creates, the shifting of identity and story. It dives into the history of racism in the United States, the censorship of media, the attacks on LGBTQ individuals, and more. While recovering Maximus’ story, Erased provides an all-encompassing history of Hollywood, early Black cinema, the United States, and the world from the 1930s through McCarthyism.

Ultimately, though, Erased itself is nothing more than an illusion, because Maximus Wyld never existed. As I read Erased, I kept wanting to look up and find more information about Maximus. I put the book down and searched for Maximus online, to no avail. I thought to myself, “Is Erased the only evidence of Maximus? Is it the only document of his life and work?” The answer to both questions, in the factual sense, is “No.” Maximus never “actually” existed, but now, through Phang and Micol’s work, he does exist as part of cinematic history, as a sign to the erased individuals of Hollywood’s “golden” age. While Cheuk and I both felt, during our initial reads, that Erased told the story of someone who lived and starred in these films, we came to the realization that Erased is fictional, but we each, as well, recognize the ways that Maximus’ story tells that while progress has been made, “there’s still a long way to go,” as Cheuk writes, “before actors of color are the heroes and antiheroes in our collective racial imagination.”