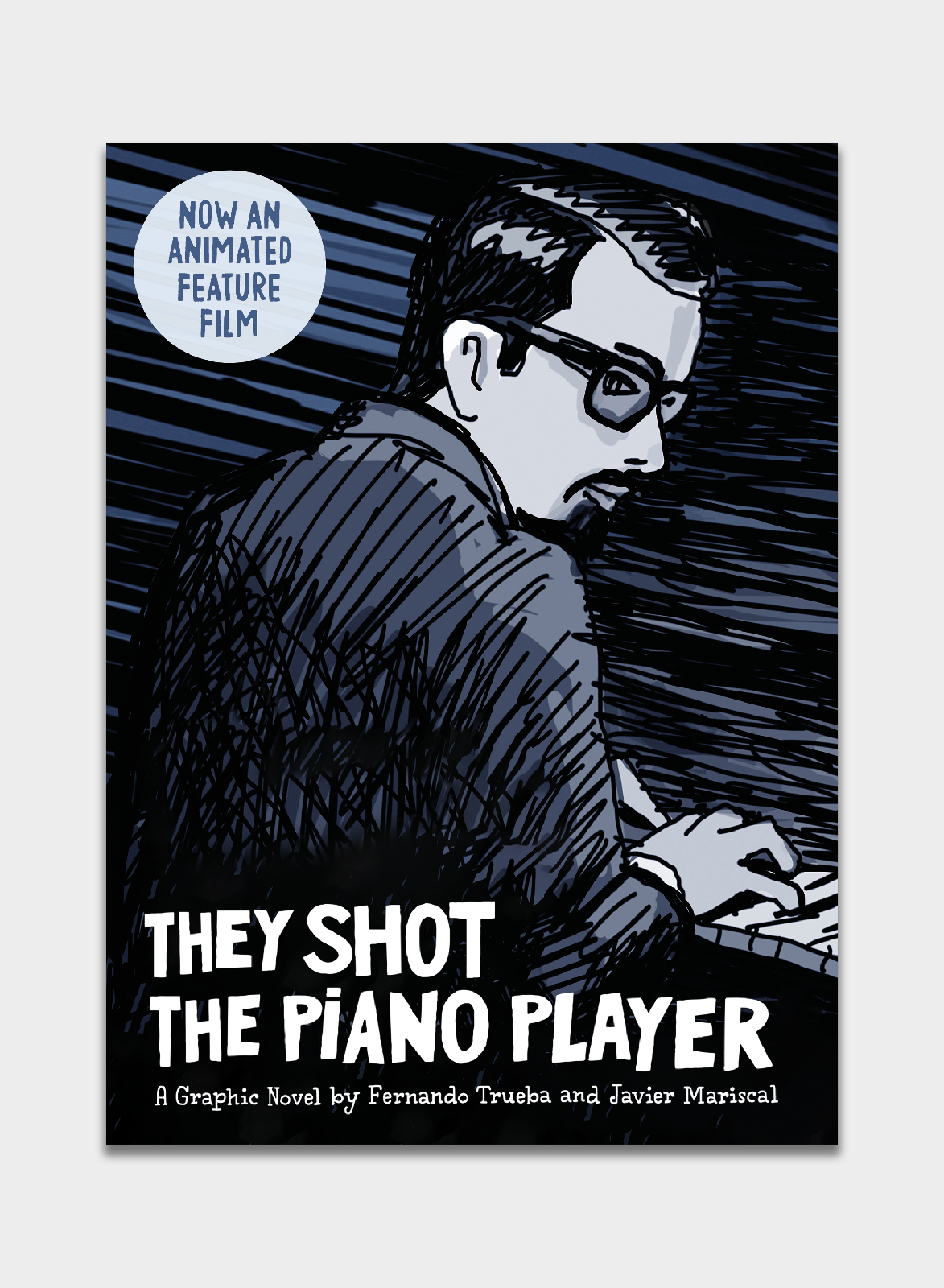

Fernando Trueba and Javier Mariscal; translated by Edward

Gauvin. They Shot the Piano Player: The Graphic Novel. London: Self-Made

Hero Publications, 2024. ISBN: 9781914224249. $34.99. https://www.selfmadehero.com/books/they-shot-the-piano-player-a-graphic-novel

While They Shot the Piano Player has been touted by The Indiependent as “a graphic novel to rival Maus or Persepolis,” this comic adaptation of the 2023 animated film of the same name fails to deliver the same syncopated rush as the jazz-soaked movie. The story follows a journalist from New York whose obsession with the mysterious 1976 disappearance of the Brazilian pianist Tenório Júnior on the cusp of a military coup in Argentina, takes readers on a whirlwind tour of the rise and fall of bossa nova and democracy in South America. This is the second graphic outing for Fernando Trueba and Javier Mariscal, the writer-artist/co-director duo behind 2010’s Academy Award-nominated film and (subsequent comic book) Chico and Rita. Published by London-based imprint, Self-Made Hero, this book falls into a similar trap of being narratively invested in music only to be portrayed by a silent medium. Many of the visual choices in translating the film to the page are questionable, proving that ultimately this story worked better via moving images rather than sequential ones.

Jeff, an American journalist interested in Latin jazz, gets consumed by the story of an obscure Brazilian pianist who disappeared during the military coup of Argentina in 1976. The framing narrative consists of a book signing in New York City where the journalist launches into the saga of discovering the truth behind Tenorio's cold case through a series of talking head interviews, featuring a who's-who from the history of Brazilian popular music. The story follows Jeff flying to various South American locales in pursuit of anyone and everyone who might have information regarding Tenorio's disappearance, including the pianist's ex-lovers, musical collaborators, and surviving family members. So as to not spoil the mystery, suffice it to say the labyrinthine tale of Tenório’s disappearance is eventually revealed as being politically-motivated. It is unclear if the narrative arrives at the final truth of Tenório’s case, as the man who "confessed" was convicted later for fraud, but it also becomes clear that as a case of kidnapping and disappearance, there will never be any true relief for those who survived him as they never got to say goodbye. In the end, the book reads like a jazz documentary / travelogue meets a chilling whodunit, providing a history of the bossa nova movement and its downfall while also highlighting the material impact of the CIA-backed Operation Condor on the lives of everyday people.

Some strengths do stand out in the adaptation, including the one I looked most forward to in the writing of this review. The sheer density of the scenic panoramic shots and the cozily-over-stuffed interiors made the film ooze with tiny background details. I craved being able to sink further into Mariscal’s visual world by poring over his drawings in book form. To get a widescreen shot of Rio de Janeiro, with mountains peppered with rooftops and beaches bursting with umbrellas, but only be able to glance at it for 20 seconds was downright cruel. For readers to be able to actually immerse themselves in the imagery and luxuriate in the tightly sketched locales was my justification for even considering reading the book version. Additionally, the color pallet of the film, particularly during the musical segments, was also ripe for adaptation, to let the saturated orangey reds and turquoises – and the iconic blue note blue of the cover – sing in print. The story itself is a fascinating history of the relatively brief zeitgeist of bossa nova music, while evergreen with its discussion of totalitarianism and the role of the state in the movements of culture. In the bonus essay in the back of the book, Trueba’s announces his goal for the film was to “resurrect” the vanished Tenório (233), arguing that animation was “the ideal form, the ideal language” for his story; this makes one wonder why he decided to make a comic book adaptation after all.

The main critique of this work is that the comic does not have a cartoonist's touch; the “talking heads” style of documentary that the film pulls off in a novel way through the use of roto-scoped animation does not translate well into comics, except in parts where the interviews feel more like a dialogue (see the dinner scene with Suzana de Moraes, daughter of jazz musician Vinícius de Moraes, on pages 38-41). Every panel is taken directly from the film, without a shred of new material other than some sketches of Tenório in the back along with a handful of stills that were cut. The only change to the imagery was re-framing shots to fit into panels along with the addition of hand-drawn sound effects and emanata. In terms of framing, occasionally characters are zoomed in on to break up the monotony of the tripod interview segments. But, unlike zooming in with a real camera, these images are just blown up, showing the roto-scoped characters in even sparser detail. Compared to the intricate long shots of landscapes, these close-ups felt wildly out of place, making an uneven visual narrative. The shot-reverse-shot procedure for interviews makes for a tedious and formally bland comic as well, so transitions between scenes sometimes would make certain stills from the film into splash pages or two-page spreads to break up the rhythm of the text. However, the choice of spreads felt arbitrary, breaking up the narrative with images that did not scale up sufficiently, which looked cheap next to densely-packed panoramas jammed into tiny panels with no room to breathe. As a student of both comics and animation, I was surprised and disappointed with how jarring this visual mistranslation felt as a reader, but it did serve as a reminder that comics are not just film-lite.

In terms of audience, ideal readers would be fans of the film or fans of bossa nova and Latin jazz generally. Those interested in a similar aesthetic experience but without the jazz might also enjoy the Aya series (Aya of Yop City, Aya: The Secrets Come Out, etc) written by French-Ivorian Marguerite Abouet and drawn by Clément Oubrerie, or Miss Don’t Touch Me by Hubert and Kerascoët. Oubrerie and Kerascoët both utilize a gorgeous color story, while Oubrerie portrays the bustling streets of Yopougon and Abidjan with loving detail. A more politically-charged work to read alongside Player would be Israeli cartoonist Rutu Modan’s Exit Wounds or The Property. While the Dramatis Personae in the back of Player is useful in keeping track of characters, and the special essay provides trivia and insight into the film’s production process from Trueba’s point of view, ultimately, I suggest just watching the film. Maybe next time, I should just buy a Mariscal print off his portfolio website instead to really sink my teeth into his drawings.