As someone who occasionally curates comics exhibitions in Singapore, attending the 2024 Angouleme Comics Festival (after a 10 years hiatus due to work) has been an eye opener and given me ideas on how to curate shows in the future.

Articles from and news about the premier and longest-running academic journal devoted to all aspects of cartooning and comics -- the International Journal of Comic Art (ISSN 1531-6793) published and edited by John Lent.

Thursday, March 7, 2024

Vampires rule at Angouleme 2024

Saturday, March 2, 2024

IJOCA's main website is down - a workaround

let you see a capture of the site from February -

https://web.archive.org/web/20240204060857/http://www.ijoca.net/

Friday, March 1, 2024

Nate Powell interviewed about Fall Through, his punk rock graphic novel (UPDATED)

Interviewed by CT Lim

The March trilogy, written by the late civil rights leader and U.S. Congressman John Lewis and Andrew Aydin, and illustrated and lettered by Nate Powell, was one of the most acclaimed series in recent years. It is the first comics work to ever win the National Book Award and there is even a sequel now called Run. But most readers of that series will not know the artist of the books used to be in a punk band, ran his own punk label, and drew comics about the life.

When I had the opportunity to review his new book, Fall Through and to interview him via email, I knew this is what I wanted to focus on. Reading Fall Through is like reading issues of Maximum Rock 'n' Roll and thinking about 'what is punk?', 'what is authentic?', and 'how does one carry on in your 40s and 50s after a lifetime of listening to rock 'n' roll, subscribing to its ethics and ideals when you have been working a 9 to 5 job for the last 20 years?' You realized there is a cap to what you can achieve in the rat race, in climbing the corporate leader. There are some things you just won't do and don't believe in. You can only be 'good' for so long, then you just got to throw a spanner in the works. Because it makes life more interesting. Some of these dilemmas are discussed in Notes from Underground: Zines and the Politics of Alternative Culture by Stephen Duncombe.

I thank Nate Powell for his illuminating and generous answers to my questions. I learn that his punk characters are connected in his own story universe. I look forward to reading his new books.

How does one go from being a punk rocker to being an award-winning comic artist?

I began my active involvement with both communities simultaneously; In September, 1992, my band Soophie Nun Squad started writing songs as my bandmate and I published our very first comic book, D.O.A. #1. My comics pursuits were initially separate from my more personal fanzine creations, slowly merging as I realized that comics could be used to express whatever I wanted. Soophie Nun Squad’s first tour in 1997 doubled as the first time my comics were sold outside my hometown, and more importantly, read by any audience who didn’t already know me. These creative and social networks in punk and comics are both parallel and interconnected, and I’ve simply continued doing what’s been so meaningful for the past 32 years.

What are the lessons that you have learned from punk rock in general, and those that you have applied to being a comic artist?

Punk can be understood as a lens through which to navigate one’s surroundings and to better understand one’s relationship to the world. It can also be a means of problem-solving, figuring out ways to make things real on one’s own terms, and often with limited resources. It’s a test of faith in strangers and their intentions. It’s a crucial exercise in the value of critical thinking skills.

What we call punk is also a double-edged sword: it’s eternally defined and redefined by young people, and the older one gets, the more important it is to reevaluate those self-imposed values and structures we set in place as teenagers. The most enduring of these values in my middle-aged life are a strong do-it-yourself ethic, the necessity of community engagement and faith, and the unique strengths of comics’ democratized accessibility as an expressive medium.

What I like about Fall Through is that it is not a straight narrative of a band on the run. It attempts to capture what it is to be on tour, the constant gigging, to be skint all the time and you feel you just can't get off the road. It's like reading an issue of Cometbus, more akin to George Hurchalla's Going Underground than Michael Azerrad's Our Band Could be Your Life. The latter is more structured while the former is more shambolic and a bit all over the place.

Or am I reading it all wrong?

That’s definitely a big part of it. On the surface level of the plot, that disorientation and closed perspective is a powerful force when touring with the kind of band-family we see with Diamond Mine. But the tour aspect of the book is really just the scaffolding that holds deeper themes and feelings in relation to each other. A deeply personal creative collaboration like a punk band often carries a dynamic tension between band members’ perceived unity of purpose and the individual visions and motivations of its members. We sometimes lie to each other about these intentions, just as we lie to ourselves.

How much of the magic realism was there when you first outlined the story? Was it something that you had in mind or something that came along the way? (I thought it was a good way to make tangible the lure of the road, to keep on going and going and to put aside reality and the real world)

All of my solo fiction is magical or supernaturally-tinged, and it all takes place as isolated tales within a shared universe, allowing me to explore different aspects of my beloved hometown, its unique culture and people. So for Fall Through, magic was a given possibility during the early problem-solving stage of writing. Diamond Mine first appeared as a band in my 2018 book Come Again, performing in a weird mountain town in 1979. As I was developing these characters and their stories for Fall Through, which takes place in 1994, I embraced the fact that they simply don’t make sense in either era, and realized that this was a central mystery to help unlock the larger story. Finding a way to reconcile this without overexplaining it required reverse-engineering the band’s appearance in 1979, piecing together details which directly revealed the central plot issue, and allowed me to build around that mystery.

Are you still in a band? Will you form another one?

I have been a parent for the last 12 years, and that takes up every second of my life. I’m also geographically separated from the people with whom I’ve been involved in all of my bands—when I say “band-family,” I really mean that. It’s proven to be very difficult to play music outside of that family, but has made any reunions very welcome. From 1992 to 2010 I was in the bands Soophie Nun Squad, Gioteens, Boomfancy, Wait, Divorce Chord, and Universe, all with overlapping membership. In 2023, I reunited with three other members of Soophie Nun Squad to play a tribute set to a beloved hometown punk band, Trusty, doubling as a memorial to their drummer Bircho, who passed away at the beginning of the pandemic.

What music are you listening to these days? What would you recommend? What would be a playlist to accompany the reading of Fall Through?

When I draw, I often listen to ambient electronic and minimalist albums on repeat—a lot of Harold Budd, Brian Eno, OK Ikumi, Oneohtrix Point Never, Philip Glass. I certainly spend a lot of time listening to emotionally vulnerable hardcore of the mid-80s to mid-90s—that’s my home planet. Lately, I’m constantly listening to Cocteau Twins, Prince, Siouxsie & The Banshees, Hugo Largo, and The Cure, as well as stellar new albums by Hammered Hulls and Scream.

I actually made a soundtrack accompaniment to Fall Through, which is here: https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLF5hlx163lp15p6uNFVRtlIcKy3-81i3d

Some friends of mine (old punks) in Singapore are talking about planning for punk lives after 50, 60. Those who are not married or have kids, is there a retirement home for them so they can take care of each other. A punk house but with the old people safety features. This could be a real concern as people expect punks to 'grow up', settle down, have a proper 9 to 5 job, establish their careers. (one became a lecturer in an arts school and doing her PhD now on punk culture in Singapore, mining her own past) But some don't and there is some talk about punk old folks' home.

Are there similar issues in USA?

This is a good example of the importance of reevaluating how we apply these lifelong ideals crystallized as, and by, young people. There is not a serious issue with settling down and growing in different directions as we age. It’s simply what people do, and denying that requires an increasing denial of our relationships with the world—which is precisely how Diana has painted herself into an ideological corner with her own misapplied, self-serving idealism.

Punk is a way of approaching what we do, how we do it, and how to best look out for each other. There is no dichotomy-crisis outside of young adults who don’t yet understand this—and older people who refuse to acknowledge it. Punk is very real, and also a fabricated misnomer.

What's next after Fall Through?

In April, my next nonfiction book will be released. It’s a full comics adaptation of James Loewen’s influential Lies My Teacher Told Me, which is essentially a history book about intergenerational misunderstanding of US history through our history textbooks. The original version of this book was very influential on me as a young adult, and it has only become more significant as the power-hungry, reality-averse far right in the US have pursued organized campaigns to ban books and control information and diverse voices within the American experience. As for what’s on my drawing table right now? I’m finishing pencils on the prequel to Fall Through, which is both a stand-alone character study centered around Diana and the connective tissue fusing Come Again to Fall Through. It’s been a blast to dive so deeply into these characters’ lives and psyches, and will be heartbreaking to reach the end of the journey again.

BY NATE POWELL

Abrams Books, 2024

ISBN: 9781419760822

- (Updated 3/2/24 with introduction)

Thursday, February 29, 2024

Book Review: All-Negro Comics (the 75th Anniversary Edition)

reviewed by Cord

Scott, UMGC

Okinawa

reviewed by Cord

Scott, UMGC

Okinawa

Chris

Robinson, editor. All-Negro Comics

(the 75th Anniversary Edition). ANC75.com/Wizrob.com, 2023. $33.95 (hardcover). ISBN 979-8-218-13590-4. <

https://www.crob.info/all-negro-comics

>

For

many comic books of the Golden Era of the 1940s, the stories and artwork have a

certain lack of quality to modern readers.

The stories seem formulaic at times, the artwork adequate but limited in

originality or detail, and stereotypes are often utilized to simplify the

stories for the readers or just because they are part of the common visual

vernacular. It is not surprising that All-Negro

Comics at first glance might seem of little overall impact. In terms of business success, it was true.

But historically, this could not be further from the truth. This comic, originally produced in 1947,

might not have had a lasting impact for the average (white) comic book reader,

but when analyzed against the history of the era as well as that of the comic

book industry, this Anniversary Edition allows a much fuller picture of

its long-term impact. The purpose of the comic was, as journalist and the original

editor Orrin Evans wrote, to “tell, teach and tribute” a mission this reprint

edition continues. The reprint project, funded on Kickstarter < https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/1084996367/all-negro-comics-75th-anniversary-edition>

raised over $35,000 from 656 people to bring the comic back into print, with

copies given to several school and public libraries.

The

book is structured in three sections.

The first 50 pages are the original All-Negro Comics number

one. The stories as they appeared in the

comic included “Ace Harlem,” a detective (written by Orrin Evans and inked by

John Terrell); “Dew Dillies” written by Cooper about how semi-mythical entities

act and interact; “Ezekiel's Story,” a two-page essay; “Lion Man” by George

Evans where a scientist/hero strives to keep uranium safe for the UN from

unscrupulous villains, “Hep Chicks on Parade”; “Lil Eggie”; and “Sugarfoot and

Snakeoil” by Cravat, in which two travelling men look to gain a meal and a

place to rest.

The

second part of the book consists of brief essays on the impact of the comic on

the African-American community in more recent years. In the first essay, Qiana Whitted noted the

significance of a comic book written, illustrated and meant for an African-American

audience in an era where legal segregation was still the norm. Many of the artists came from the

Philadelphia School of Art and had had interactions with Evans previously. Whitted also noted the history of African

American centered comic strips from “Sonny Boy San” in the Pittsburgh

Courier, and “Bungleton Green” from the Chicago Defender. While newspapers may not have the same significance

in the era of the internet, in the 1940s they were fundamental in providing news

and entertainment centered towards an underserved segregated community across

the country. Unfortunately, Evans’ bold

idea never made it past the first issue.

David Brothers stated in his essay “Hip Hop and Comic books was my

Genesis” that the idea of African-American characters, especially those not

merely as sidekicks or stereotypes, was fundamental in his own creative

path. Shawn Pryor’s essay “Finding My

Path” states that racism still exists in the comic book industry despite the

progress made, albeit now in the form of monetary compensation, and unstated continuing

policy from an earlier era of editors which rarely hired black creators.

The

third section of the book starts on page 66, and features new storylines

created from the original characters.

Ace Harlem now struggles to deal with the issue of “white benefactors”

who see themselves as betters for helping those less fortunate, while attempting

to camouflage their own racism. The new

Lion Man story features issues of stereotypes and propaganda that dominated so

many of the early comics and twists it to work for the character. His faithful sidekick/ward Bubba still remains,

but is not so much a hinderance but a imp working for Lion Man’s

interests. The essay in this later section

is “Nana’s memory quilt” by Samantha Guzman.

The story discusses both the inevitability of death, but also how items

such as quilts can help to preserve not only memories but also family history. This later aspect is one that has traditionally

been overlooked when dealing with cultures with written, as opposed to oral or

pictorial histories. Finally, the last

significant story featuring the Dew Dillies centers on “Platypus and the

Swan.” The moral of the story is that

both animals swim and have significance in the world despite their perceived aesthetic

qualities.

As

with any review of Golden age comics, there are aspects that still stand out

for their inappropriateness. While

Whitted noted that Evans was trying to balance stereotypes with strong

characters who were equals in the comic book world, there was still a

considerable amount of sexism, be it from calling a female character “sugar” or

“honey” to the original Sugarfoot’s object of desire, Ample Mae, and her well-proportioned

and commented-upon figure. The concept

of taking the original comic and creating new stories was interesting. It showed the impact of the original as a

springboard to the present. One of the

areas that could have been expanded would be the history of the creators, and

their backgrounds and other works.

In

all, the book is a starting point for a research area that is significant, but

not well-developed. One could then also at the impact of newspaper artists and

their contributions to beyond comics.

Did any of the artists have connection to Army newspapers such as the Blue

Helmet or the Buffalo, both of which catered to (segregated) Army

units during World War II? Or the black

superhero artists of the 1970s-1980s? This book, as with so many others, offers

a good reference point, but is not the whole story.

Wednesday, February 14, 2024

IJOCA 25:2 Delayed

IJOCA 25:2 Delayed

IJOCA has prided itself for coming out within due seasons, but, unfortunately, that will not be the case with 25:2,

This issue is delayed, because.

1. It is our silver anniversary issue, and to celebrate the occasion, we are including celebratory drawings and statements that have been (and still are) arriving.

2. This issue includes a thorough index of all 25 years' contents, which took large amounts of time compiling, proofing, and putting into final form.

3. The editing of the articles is taking up much time because of grammatical, typographical, and factual errors that needed remedying.

Please accept our apologies and bear with us.

John A. Lent

Friday, January 19, 2024

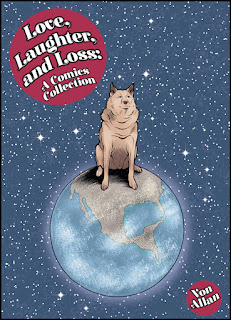

Letting the Everyday Speak its Own Power: The Works of Von Allan - A Review Essay

by David Beard, University of

Minnesota Duluth

by David Beard, University of

Minnesota Duluth

Canadian graphic novelist Von Allan (a pen name) persistently plays

with the tension between the mundane and the enchanted in his work, which is

usually self-published. In Love,

Laughter, and Loss, Allan funnels the enchanted and the emotionally

powerful through stories that emphasize the mundane, sometimes for humorous effect,

sometimes for tragic. In Wolf’s Head,

probably his best work to date, the fanciful elements of a science fiction tale

are masterfully pulled into a grounded, emotionally realistic story about a

child grappling with their mother’s legacy. As Allan has moved into nonfiction

(both in his public writings for the Ottawa

Citizen and in participating in the documentary I Am Still Your Child), he continues to pull us deeper into the

everyday, hoping to find the meaningful, and the tragic, therein.

Allan introduces us to Lauren’s mom with the same techniques. I absolutely adore this first image of her mom (all solid colors and dark, thick lines), in sharp relief against (again) the complex textures of the apartment hallway and doorframe. On first, quick read, it’s possible to miss the oddly shaped musical note coming from her bag.

Wolf’s Head is at its best in the small things – Lauren’s search for meaning after leaving the force, her reunion with her mother. The story of the self-aware machine is the tiny twist that helps bring Von Allan’s gift for bringing the everyday into view. It’s difficult not to read this touching, loving mother-daughter relationship in Wolf’s Head without a sense of Von Allan’s interest in mental illness in families. His 2009 work, the road to god knows, is no longer in print, but the narrative arc (of a mom separated her from her child) resonates.

In Dave’s case, the medication emotionally

“flat-lined” him. He phrased it this way: all of his emotions, not just the sad

ones, were shunted off. Not sad, not filled with loss, but equally missing out

on happiness and joy. There was just nothing at all. As a result, Dave gave up

on the medication. He never did try another.

No hyperbole, no drama – whatever emotion you draw from Foohey’s

story, you draw from the straightforward presentation of Dave’s story.

Von Allan Studio website: https://www.vonallan.com/

“Julien: Dave's Story — and the Agonizing Dilemma of Mental Illness.”

Ottawa Citizen July 4, 2022

Love, Laughter, Loss. Ottawa: V. Allan Studio, 2021.

the road to god knows. Ottawa: V. Allan Studio, 2009.

Wolf’s Head. Ottawa: V. Allan Studio, 2021.

I Am Still Your Child. CatBird Productions 2017

“Childhood Innocence” Does Not Need Rescuing Here : Growing Up Graphic book review

reviewed by Cecilia Garrison,

Growing

Up Graphic: The Comics of Children in Crisis is a refreshing

and honest assessment of the importance of accurately and frankly acknowledging

that childhood innocence is a Western invention. And also, that children, no

matter where they are from or who they are, deserve to see themselves depicted

in comics and can use the graphic narrative medium as a means to develop a

broader and more realistic world view. Alison Halsall, fresh off the success of

her edited volume The LGBTQ+ Comics Studies Reader winning the 2023

Eisner Award for Best Academic/Scholarly Work, writes Growing Up Graphic with

four objectives in mind. First, Halsall aims to explore comics and graphic

narratives as a medium heavily invested in representing the reality of the

social, political, and cultural experiences of childhood and youth. Graphic

narratives, she argues, are a particularly useful means of sharing these

experiences across national and cultural borders, because the “unique

verbal/visual interface” (28) of these narratives seems to translate across the

borders more easily. The second objective is the navigation of comics for young

people throughout, within, and around “discourses of nation, belonging, ableism,

and identity” (3). Young people are shaped by the communities and countries in

which they live, and the politics of those spaces, and they deserve to have a

space in that discourse. Third, she observes and contends with the trend in

children’s publishing to diversify published content, providing young readers

in the Global North with a more intersectional lens through which to see the

world when consuming media. Comics and graphic narratives for children use the

personal and the local to aid young readers in understanding broader

narratives. And finally, she considers the readers themselves as a source of

tension. Halsall meets all her stated objectives with aplomb and a frankness

that makes the book hard to put down.

Halsall’s text refutes the harmful ideas that comics and

graphic novels are somehow lesser and should not be consumed by children or

young people because of supposedly harmful and corrupting influences. This idea

has existed for decades; today’s censorship of LGBTQ and African-American graphic

novels echoes Fredric Wertham’s 1950s crusade against comics. However, Halsall argues that the world in which we all

live requires more and more of

children, particularly in terms of communication and critical thinking skills.

Visual literacy, comprehension, and interpretation are increasingly necessary

aspects of communication. More libraries, schools, and curricula for young

readers find the navigation of graphic texts to be a valuable means by which

students and readers can develop these and other skills, while also developing

a love of literature, art, and reading from a young age. Not only do graphic

narratives provide opportunities for young readers to develop the

aforementioned skills, but the particular graphic narratives Halsall addresses

in Growing Up Graphic (which include such titles as War Brothers by

Sharon E. McKay, Leila Abdelrazaq’s Baddawi, 7 Generations by

David Alexander Robertson, and several of Raina Telgemeier’s graphic novels,

including Guts and Drama) provide young readers with new and

engaging opportunities to learn about human rights discourses, world events,

and ways in which children are and can be active agents in the world around

them, providing the groundwork for those readers to become more empathetic,

compassionate, and culturally aware.

Furthermore,

Halsall questions the Global North belief that childhood and youth are and must

be innocent – that children should be protected from anything that may burden

the innocence of their youth. Childhood, Halsall argues, is a largely Western

concept, and that the Global North conception of childhood as something which

should be stable and protected is in conflict with the experiences of hundreds

of thousands of children both within the context of Western societies and

beyond. This conflict is present throughout all five chapters of Growing Up

Graphic.

In

her first chapter, Halsall explores the use of childhood in war, bringing the

reader through an analysis of Michel Chikwanine’s Child Soldier: When Boys

and Girls Are Used in War, Sharon E. McKay and Daniel Lafrance’s War

Brothers: The Graphic Novel, and Jean-Philippe Stassen’s Deogratias, A

Tale of Rwanda to ask readers to reflect on the ontology of victimhood, the

lives of those – especially children – who are caught up in wars not of their

own making, and the impacts of power, control, and change. She calls upon these

texts to defamiliarize standard historical narratives and the ideas of

childhood, as they instead point out that history is far rifer with personal

and political violence and trauma, and that childhood “transforms in relation

to war, a social and political crisis” (34). The children involved in armed

conflict cannot be seen from the Western perspective of childhood as brimming

over with innocence, they are shown through these narratives to be complex;

neither agents nor at-risk victims, but perhaps both at the same time. They can

be agentic without being responsible, vulnerable without being entirely

victimized, etc.

This

vein of complicated agency continues into the second chapter, with a question

of how graphic narratives about immigration, diaspora, and refugees, such as

Morten Dürr and Lars Horneman’s Zenobia, Shaun Tan’s The Arrival,

Matt Hyunh’s “The Boat,” Reinhard Kleist’s An Olympic Dream: The Story of

Samia Yusuf Omar, Leila Abdelrazaq’s Baddawi, and George Takei’s They

Called Us Enemy, can explore migration ethically, rejecting the instinct

common in Western literature to represent refugees and immigrants as “passive

victims waiting to be ‘saved’” (58), instead exploring them as fully complex individuals

shaped by the circumstances in which they find themselves. This effort

humanizes the refugee crisis and the protagonists of these texts, allowing

young readers to ground themselves in another young person’s lived experiences.

“Here” and “there” become less disparate as young readers read, and they are

able to conceptualize immigrants and refugees as something more than victims

without agency, awaiting saving from the Global North.

The

theme of agency and refusing to see marginalized protagonists as victims in

need of saving continues throughout the text. Chapter 3 of Growing Up

Graphic focuses on Indigenous texts from Canada, exploring the way that

texts such as Katherena Vermette’s A Girl

Called Echo, David Alexander Robertson’s 7 Generations, and Michael Nicoll Yahulanaas’s Red: A Haida Manga explore the healing powers of language and

visual storytelling to explore myth and worldview, and address the generations

of systemic violence and genocide faced by Indigenous communities. While this

chapter addresses and acknowledges injustices, both past and present, the texts

analyzed within seek to empower Indigenous youth, providing a narrative that

emphasizes cultural affirmation, renewal, and hope while responding to a

history of colonial violence. The texts encourage young readers to question

historical narratives, resist the erasure of violence and colonialism, and work

against the continued racial stratification and systematic injustices. Not only

does the use of graphic narrative offer Indigenous writers and readers

catharsis and critical reflection, but it also provides non-Indigenous young

readers with valuable perspective while not viewing Indigenous peoples

non-agentic or their lives and stories as something to be relegated to a

history book.

Chapter

4 takes particular umbrage at the concept of protecting the innocence of

childhood by highlighting the powerful importance of quality representation of

queer identity in texts for young readers, complicating the idea that children

must be separated from any knowledge of sexuality. Halsall argues against both

an ideal of a stable, protected childhood and a stable sexual and gender

identity, acknowledging that both of these concepts are likely to fluctuate,

change, and have different meaning for different people over time. She examines

texts such as Mariko Tamaki’s Laura Dean Keeps Breaking Up with Me, Hubert

and Marie Caillou’s Adrian and the Tree of Secrets, and Ngozi Ukazu’s Check,

Please! to understand how they normalize the queer experience, reorienting

the narrative of queer media away from the trauma and crisis often associated

with queerness to the conflict ubiquitous in young people’s interpersonal

relationships. The context of this chapter within the rest of Growing Up

Graphic is interesting, because the texts Halsall examines here are creating

narratives wherein existing as queer is not, inherently, a crisis. However, the

texts themselves are seen as a crisis, as political and cultural groups

continue to try to protect young people from anything perceived as sexual. Such

groups harken back to “the pervasive myth of the implied Romantic child reader,

whose purity is necessarily incompatible with sexual awareness and experience”

(131) and consider such texts inappropriate for young readers. These texts,

however, are continually and increasingly important for readers, as they seek

to orient themselves in relation to the world around them and develop broader

views on many issues.

All

of the texts encourage perspective taking, empathy, and compassion in their

readers, and the fifth chapter’s emphasis on health crises furthers this

objective, while also often providing information, awareness building, and

consciousness raising about what are often otherwise undiscussed parts of

people’s lives, especially when those in the midst of the health crisis are

young people. Texts such as Raina Telgemeier’s Guts or Smile,

Cece Bell’s El Deafo, and Tory Wollcott’s Mirror Mind: Growing Up

Dyslexic provide the creator and perhaps the reader with some measure of

control over what can often be a situation in which the person affected has

little to no control. Not only does Halsall address the way these texts can

normalize experience of bodily difference, chronic and/or severe illness, or

mental variance, she also speaks to the way that the texts respond to the

silence around many of these conditions, redefine the meaning of health, and affirm

the agency of those who may have such a condition, especially in the face of

families or medical professionals who may attempt to remove such agency or

voice. Halsall returns to the message of refuting the victim paradigm,

emphasizing texts that move away from the protagonist needing rescue from their

condition. Not only do graphic narratives provide the same benefit of

socio-emotional education around disability that they do the other topics

discussed in Growing Up Graphic, but Halsall also points out the ways in

which graphic narratives as a whole can be an accessible form of learning for

those with developmental disorders, learning disabilities, or other conditions

that may impact information acquisition, retention, understanding, and/or

processing (179). These graphic narratives challenge the idea of children as apolitical

and needing protection from troubling topics such as health crises or

disability, instead giving children the language necessary to approach medicine

and their bodies with agency and information.

Halsall

leaves the reader anticipating more – more comics and graphic narratives, more

from comics studies, more from Halsall herself, and, unfortunately but

realistically, more children in crisis. She concludes with an impact statement

about how the COVID crisis has highlighted discrimination in a variety of forms

across the globe and the unequal distribution of safety and power across homes

and nations, and the ways in which graphic narratives are already being used to

address various aspects of the pandemic. Still Halsall asserts, the children

don’t need protecting from the realities of COVID any more than they do from

other world crises, they need understanding, information, an outlet, and

compassion. From an explosion of digitally available comics about the

experiences of people during the course of the ongoing pandemic, to being used

to provide information about mitigating the risks of the virus, Halsall

anticipates that COVID comics will continue to prove all the ways in which

comics provide young readers with a humanizing glimpse into the experiences and

challenges faced by young people all the world over.

.jpg)