reviewed by José Alaniz, University of Washington, Seattle

reviewed by José Alaniz, University of Washington, Seattle

Bald by Tereza Čechová (text) and Štěpánka Jislová (ill.); translated by Martha Kuhlman and Tereza Čechová. University Park, PA: Graphic Mundi, an imprint of Penn State University Press, 2024. 128 pages. $21.95. ISBN: 978-1-63779-080-9. https://www.graphicmundi.org/books/978-1-63779-080-9.html

Regarding the Czech comics domestic

scene, as recently as 2020 scholar Pavel Kořínek could credibly opine: “[A]ny

kind of subjective, personal recollection remains extremely rare. Czech comics

seem — at least on their most superficial level — curiously de-personalized,

de-subjectivized, with genre and fictional works predominant. For some reason,

there have emerged very few overtly personal, autobiographical comics in the

Czech tradition” (“Facets”: 91).

Such statements

are less credible today, thanks to more recent publications such as veteran

artist Lucie Lomová’s Every Day is a New Day: A Comics Diary (Každý

den je nový: komiksový deník, 2022) — a work as personalized, subjectivized

and autobiographical as anyone could want.

In fact, the

landscape was shifting even as Kořínek’s original assessment was seeing print.

That same year Czech publisher Paseka released the groundbreaking graphic

memoir Bez Vlasů (literally “Without Hair”) by writer Tereza Čechová[1]

and artist Štěpánka Jislová.[2]

It dealt in intimate detail with the memoirist’s life after a diagnosis, at 30,

of alopecia, an autoimmune condition that leads to hair loss. No comics work

like it (certainly not in long form) had appeared in the Czech lands before. It

would later win the Czech industry’s highest award, the Muriel Prize, for Best

Comics Work.

2024 saw the

English translation of Bez Vlasů, here rendered as Bald, from

Graphic Mundi Press. It is translated by Čechová and Martha Kuhlman, professor

of Comparative Literature at Bryant University in Providence, RI and one of the

leading US scholars of Czech comics.[3]

It makes sense

that Graphic Mundi, an imprint of Penn State University Press, would take up Čechová

and Jislová’s prize-winning work, given its Graphic Medicine focus. Penn State

is a major US node of the international Graphic Medicine movement, which

centers graphic narrative representations of illness, disability and related medical

themes.[4]

Bald

certainly ventures deep into this territory; the heroine Tereza navigates — at

times painfully — alopecia’s effect on her identity as a woman, love life, work

relationships and even her pocketbook. I found these scenes on the day-to-day economics

of her condition the most illuminating: she expounds on the cost of medication,

therapists, wigs, head coverings of different sorts. We also get fascinating

discussions on the hair of different races and ethnicities, as well as on the culture

and mythology of hair (Samson and Rapunzel are just the tip of the iceberg).

Bald

certainly ventures deep into this territory; the heroine Tereza navigates — at

times painfully — alopecia’s effect on her identity as a woman, love life, work

relationships and even her pocketbook. I found these scenes on the day-to-day economics

of her condition the most illuminating: she expounds on the cost of medication,

therapists, wigs, head coverings of different sorts. We also get fascinating

discussions on the hair of different races and ethnicities, as well as on the culture

and mythology of hair (Samson and Rapunzel are just the tip of the iceberg).

All this is

rendered in Jislová’s clean, almost schematic line that exudes a cartoony

dynamism. The book uses a two-color scheme of black lines with light reds to

produce numerous effects, like the “ghost hair” which Tereza has lost. (In

this, Bald recalls Georgia Webber’s split-identity techniques in her

2018 memoir Dumb: Living Without a Voice.)

The

author’s one-year journey as depicted makes for quite an emotional roller

coaster: despair rubs elbows with enlightened self-acceptance. A storytelling

workshop in Scotland proves cathartic. Tereza, like many people nowadays, seeks

solace on the internet, only to find confusion and – who’da thunk? –

misinformation. A brilliant page design reifies her anxieties and stresses into

a fractured three-tier portrait as our narrator tries desperately to forestall

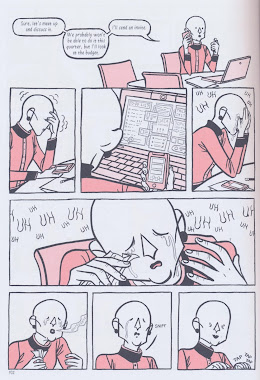

the inevitable with useless pills and creams. Another rather chilling episode

portrays her at her job, “dealing” with her hair loss by trying to ignore it

with overwork. Over eight panels, she melts down in tears before her laptop,

then resumes typing with a smile. Finally, another portrait, a splash, shows

her weeping on an armchair as supportive comments roll in after her first

posting online about her alopecia. This brief catalogue gives a sense, I hope,

of Bald’s dizzying affective spectrum. Overall, it paints a powerful

picture of physical difference and its mental health/social/cultural

ramifications in late capitalism.

The

author’s one-year journey as depicted makes for quite an emotional roller

coaster: despair rubs elbows with enlightened self-acceptance. A storytelling

workshop in Scotland proves cathartic. Tereza, like many people nowadays, seeks

solace on the internet, only to find confusion and – who’da thunk? –

misinformation. A brilliant page design reifies her anxieties and stresses into

a fractured three-tier portrait as our narrator tries desperately to forestall

the inevitable with useless pills and creams. Another rather chilling episode

portrays her at her job, “dealing” with her hair loss by trying to ignore it

with overwork. Over eight panels, she melts down in tears before her laptop,

then resumes typing with a smile. Finally, another portrait, a splash, shows

her weeping on an armchair as supportive comments roll in after her first

posting online about her alopecia. This brief catalogue gives a sense, I hope,

of Bald’s dizzying affective spectrum. Overall, it paints a powerful

picture of physical difference and its mental health/social/cultural

ramifications in late capitalism.

As Čechová told

Czech Radio, “I was really worried that the result would seem depressing,

because the comic does describe something that is very difficult. But it also

brings with it a lot of funny moments. We wanted to show that even if you go

through something like this, the world doesn’t fall apart” (Jančíková, “Cesta”).

Yet even the “funny moments” tend to have their edge. At one point, Tereza’s

boyfriend tells her, “The hair is fine. But not having eyebrows is creepy.”

Given that one of Tereza’s fears is living life alone due to her hair loss,

that comment seems less than reassuring.

Other moments I

found borderline disturbing. Trying to make herself feel better about her

condition at times leads to some dark corners, like this statement, which

sounds lamentably eugenicist: “I often think we had it coming. Humans no longer

need their hair. It’ll disappear in time. Evolution. Maybe I’m a member of a

new … more perfected race. But let me tell you, it’s not easy being one of the

first.” This textbox accompanies another portrait, of a half-naked Tereza

crying in the mirror.

Something else

which some may find rather distancing about Bald: what at times seems

like a willful opacity. By that I mean the text proceeds with great economy,

with an average of only about 20-25 words per page. It’s almost telegraphic.

This puts more of a burden on the art to carry the narrative, which Jislová

does more than capably. However, some choices have the effect of keeping the

reader (this one, anyway) at arm’s length. Jislová’s figures do not have eyeballs,

just black dots for eyes, and a puppet-like angularity to them (Tereza’s nose

looks like a sort of stylized diamond or arrow point). This choice risks

narrowing the expressive latitude of the characters, like watching a drama

acted out with dolls. (Maybe Jiří Trnka dolls? Though a lot of them had

eyeballs.) So that when Tereza has tears streaming down her cheeks it might look

to some readers as simply grotesque, and be less likely to provoke empathy/understanding.

Something else

which some may find rather distancing about Bald: what at times seems

like a willful opacity. By that I mean the text proceeds with great economy,

with an average of only about 20-25 words per page. It’s almost telegraphic.

This puts more of a burden on the art to carry the narrative, which Jislová

does more than capably. However, some choices have the effect of keeping the

reader (this one, anyway) at arm’s length. Jislová’s figures do not have eyeballs,

just black dots for eyes, and a puppet-like angularity to them (Tereza’s nose

looks like a sort of stylized diamond or arrow point). This choice risks

narrowing the expressive latitude of the characters, like watching a drama

acted out with dolls. (Maybe Jiří Trnka dolls? Though a lot of them had

eyeballs.) So that when Tereza has tears streaming down her cheeks it might look

to some readers as simply grotesque, and be less likely to provoke empathy/understanding.

Furthermore, Čechová’s

low word-count writing has a similar coldness and detached matter-of-factness,

even when discussing depression, social anxiety, desire. The author seems to

acknowledge this stance in a scene where she and her boyfriend are having

trouble communicating. “How hard it is for me to talk to anyone about my

feelings,” she says in a caption. Finally, I would have appreciated it if Bald

had interrogated the class conditions underlying Tereza’s experiences; this is

a very middle-class portrait of alopecia, despite the occasional nods to how

people without Tereza’s privileges might fare very differently in contemporary

Czech society.

These quibbles

aside (which in any case might have more to do with my own tastes as a comics

reader), Čechová and Jislová’s graphic memoir deserves its reputation for

taking Czech comics where they had never ventured before – potently so. As Kořínek

himself put it, in a quote highlighted on Paseka’s web page devoted to Bald:

“Frankly authentic, light-hearted storytelling, in the context of Czech comics,

feels a bit like an epiphany.” All this and cartoony anthropomorphic white

blood cells too!

More than

anything else, as a graphic memoir, Bald secures Czech comics’ further

imbrication with global comics culture. Paseka itself leans into this facet on

its web page, claiming the work “continues the rich tradition of

autobiographical comics from around the world.” Transnational comics flows

(analyzed so well by scholars like Daniel Stein and Kate Kelp-Stebbins) make

such a work as Bald all but inevitable, it seems.

Its authors,

both born in the post-communist 1990s, represent a younger generation much more

closely tied to graphic narrative beyond Czechia’s borders, to say nothing of

Central/Eastern Europe’s. Jislová told me she greatly admires Tillie Walden,

Kate Beaton, Alison Bechdel and Ulli Lust, global stalwarts all. This makes Bald

a work that is very self-aware about the non-Czech traditions that it’s tapping

and incorporating. “We felt, as we were working on the book, that this is the

first time we’re doing something like this in the Czech comics scene [on this

scale],” she said (Jislová interview).

More than

anything, the graphic memoir genre gave Čechová and Jislová a framework for a

story that they felt had to be told this way. “I’m a big fan of

autobiographical comics,” said Čechová, “because they can debunk (detabuizovat)

many things and reveal that which we’re not used to talking about. That’s why I

started to think that something could come from my experiences” (Jančíková,

“Cesta”).

The genie is

definitely out of the bottle now. Working on Bald led to Jislová first

hitting on the idea of pursuing her own autographical work. The result was her

own graphic memoir, Srdcovka (2023). The title is a hard-to-translate

slang term that means basically something close to one’s heart and/or that

inspires devotion/obsession. It deals with heartbreak, growing up as part of

the first generation after communism, sexual abuse and artistic coming of age. Heartcore,

the book’s English translation, is due to appear later this year (also from

Graphic Mundi, with Kuhlman again translating).

Apart from the

authors, the US press and translator deserve praise for bringing this work to

an English-speaking readership. We on these shores are chronically,

disgracefully bereft of translations of the world’s many vibrant comics

cultures, especially those with less common languages like Czech. Thank you.

Kuhlman told me that she and Graphic Mundi had decided on Bald (instead of, say, “Hairless”) for the translated title in part because the English word resonated with “bold.” That adjective, though not at all implied in the original Czech, nonetheless applies to this book – in more ways than one.

Bibliography

Jančíková, Šárka. “Cesta

hrdinky. Autobiografický komiks Bez vlasů o zkušenostech s alopecií se

nebojí těžkých témat ani humoru.” Český rozhlas (November 2, 2020). https://vltava.rozhlas.cz/cesta-hrdinky-autobiograficky-komiks-bez-vlasu-o-zkusenostech-s-alopecii-se-8352800.

Kořínek, Pavel. “Facets of Nostalgia: Text-Centric Longing in Comics and Graphic Novels by Pavel Čech.” Comics of the New Europe: Reflections and Intersections. Eds. Martha Kuhlman & José Alaniz. University of Leuven Press, 2020:

Interview with Štěpánka Jislová. Prague. June, 2024.

Paseka web page devoted to Bez

Vlasů. https://www.paseka.cz/produkt/bez-vlasu/

[1] Tereza Čechová (née Drahoňovská) (b. 1990) studied journalism and media sciences at Charles University in Prague. She and Jislová established the Prague branch of Laydeez Do Comics, a British women-led comics organization which advances the work of female comics-makers.

[2] Štěpánka

Jislová (b. 1992) is a graduate of the Ladislav Sutnar Faculty of Design and

Art in Plzeň. She has published in several Czech and international comics collections.

She also contributed to the monumental history comics series The Czechs

(Češi, 2013-2016) and illustrated the graphic biography Milada Horáková (2020),

written by Zdeněk Ležák. Her more recent work includes the superhero satire Supro:

Heroes on Credit (Hrdine na dluh, 2023).

[3] Full

disclosure: Kuhlman is a friend; we co-edited the collection Comics of the

New Europe: Reflections and Intersections (University of Leuven Press,

2020). She provided me with a copy of Bald for review.

[4] Penn

State published my 2019 co-edited study, with Scott T. Smith, Uncanny

Bodies: Superhero Comics and Disability.