“When You Erase Human Beings, It

Starts To Get Weird”:

A Jakub Woynarowski Interview

José

Alaniz

|

Fig. 1. Jakub Woynarowski at the Manggha Museum of Japanese Art and Technology in Kraków. Wawel Castle in the background. Photo by José Alaniz. |

Polish artist, Jakub “Kuba” Woynarowski

(b. 1982) earned a Master’s degree at the Faculty of Graphics at the Academy of

Fine Arts in Kraków in 2007. He also finished his doctorate there in 2017. Today,

Woynarowski directs the Narrative Drawing Studio at the AFA. He also works in

design, installation art, comics, and museum curation, with a strong

theoretical and visual arts focus. His many books include The Story of

Gardens (2010), Corpus Delicti (co-authored with Kuba Mikurda, 2013),

and The Dead Season (Martwy Sezon, 2014). Woynarowski’s accolades

include the 2014 “Paszport” award from the weekly, Polityka, for his work

on the Polish Pavilion at the 14th Venice Biennale of Architecture

and the Grand Prix at the International Festival of Comics and Games in Łódź

(the oldest, largest such event in Central/Eastern Europe) for his comics piece,

“Hikikomori” (2007).

I met Woynarowski at the Ligatura Comics

Festival in Poznań, Poland, in 2010. I have long found his work intriguing for

how it operates at the intersection of comics, fine art, and posthumanism.

While on a trip to Kraków in Summer 2024, I took the opportunity to see “Background,”

an exhibit Woynarowski co-curated at the Manggha Museum of Japanese Art and

Technology (see review elsewhere in this issue). After he kindly gave me a

guided tour, we sat down for an interview.

— José Alaniz

This interview was conducted in Kraków on June 23, 2024. It has been condensed and edited for clarity.

José Alaniz: You do a lot of different things in a lot of different media, but here, I’d like us to speak mostly about your comics-related work. Let’s begin with what you were telling me about your experience at the Academy of Fine Arts, where you teach narrative drawing. You mentioned you had to talk your superiors into letting you do it.

Jakub Woynarowski: It started in 2009, when a friend of mine, a professor at the academy who’s also a great fan of comics, invited me to take part in this initiative. We organized two different comics workshops in 2009 and 2010. We wanted to see how many students would be interested. Would there be a response to this subject? And there was--a huge response. We’re talking hundreds of people that contacted me about it. So, then we worked to convince them to open the studio. They resisted. We had proof that people were interested, so, it wasn’t about lack of students. The resistance came more from the idea that comics were not considered an art form.

JA: Sounds familiar!

JW: Yeah. They thought of it as “just” popular culture, mass culture. Because, you know, these people had no idea about the diversity of comic art. They thought, “How diverse could it be?” So, I showed them a lot of experimental stuff, like Richard McGuire, as well as fine artists who also do comics. I put together an assignment for the students, inspired by Chris Ware, to create their own hypertext comic with a non-linear structure. They did great. Very nice, very cool. They made abstract comics, wordless comics inspired by poetry. You can take something like Ware’s Building Stories (2012) as a model. Building Stories is a kind of hypertext in the sense that it’s made up of many different pieces in different formats, which you can read in any order. You have to piece it together in your mind. So, ultimately, we succeeded in implementing the program. I’ve led it from the time I got my Ph.D., in 2017.

JA: Did you grow up in Kraków?

JW: No, in a smaller city, Stalowa Wola, in Southeastern Poland. About three hours by car from Kraków. I came here for secondary school when I was 15. I’ve lived in Kraków ever since. Many of my friends moved to Warsaw, but I started to work here, and I found a good environment. Warsaw and Kraków are completely different. So, it depends on what your focus is, what you like and what you want to get done, that determines where you want to live. Warsaw is more busy; everything there is very fast.

JA: My understanding has always been that Kraków is a better preserved city, while Warsaw was much more damaged during the war. You can totally see that; it’s a lot more medieval-looking here.

JW: Right. In Kraków, the architecture is completely different, more historical, yeah. It’s a kind of hybrid situation. But you know, Kraków also has another city center far from the historical center, built under socialism.

JA: I was there yesterday! I was in Nowa Huta.[i] I got to see the Beksiński[ii] permanent exhibit there. Pretty grotesque dystopian horror. What do you think of his work?

JW: I like some of his works, especially the early ones. Some consider him a problematic artist because he switched from one field to another. He started as an avant garde artist and moved more into popular culture. Also, many people have other problems with him. I think he was an intriguing figure, because painting was only one of his interests. He was also a fascinating photographer; he created experimental audio art; he was a writer, a video artist documenting the process of creating the paintings. And, his commentaries were very ironic; he was conscious of what he was doing. So, maybe it’s kitschy, but I love it.

JA: Also speaking of Nowa Huta, I was curious what you think of the pissing Lenin.[iii] It reminds me of David Černý.[iv]

|

Fig. 2. “Fountain of the Future”

(a.k.a. Pissing Lenin) by Małgorzata and Bartosz Szydlowski (2014), in the Nowa

Hura district of Kraków. |

JW: That came

about during an international festival ten years ago. Many different artists

were invited to Poland. They, along with Polish artists, created some artistic

interventions in the public space of the city. You could link this type of

irreverent art to movements in the Communist era that were making fun of

official culture. Especially in the 80s, there were groups of artists inspired

by punk and Pop Art.

JW: Yeah. I

liked what he would do on the margins, all this strange stuff made of

spider-web. Organic figures. Or Venom, with this black stuff all over the

place. I used some of these elements in my own comics.

|

Fig. 3. Roy Lichtenstein’s “Cow Going Abstract” (1982). |

|

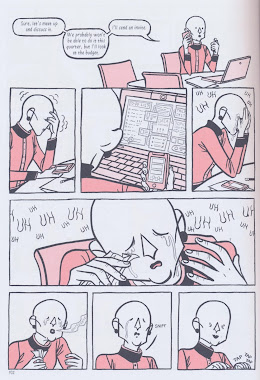

| Fig. 4. Woynarowski’s “Hikikomori” (2009). Note Todd McFarlane influence. |

JA: What was it about these manuals that inspired

you?

JW: I really liked doing technical drawings when I was a child. We did them at school; it was mandatory. My friends hated doing them, but, I really liked it, because of its precision and this infographic structure that I thought was so nice. I started turning these single drawings of objects into sequences of images.

|

Fig. 5. Franz Kafka’s “Accident Prevention Regulations on

the Use of Wood-Planing Machines,” written for the Workers’

Accident Insurance Institute for the Kingdom of Bohemia in Prague, where he

started working in 1908.

|

Fig. 6. Marcel Duchamp’s “Chocolate

Grinder No. 1” (1913), a sort of “bachelor machine.” |

|

Fig. 7. Jan Lenica’s “Labyrinth”

(1963), a classic of Eastern/Central European animation. |

When I was in secondary school, around

the late 90s, beginning of the 2000s, there was a group of Polish fine artists

born in the 70s, who were actively producing for galleries, but, at the same

time, they were making comics. And, probably, they were one of the big

influences for me. For example, Wilhelm Sasnal.[xix]

He’s a quite famous Polish painter now, but when he started his work, he was

working in Grupa Ładnie [Ładnie Group], which means, “the guys who are doing

nice things.” “Ładnie” means nice, but, of course, here, it was ironic. It was

a kind of Polish pop art mixed with 90s punk art zine aesthetics. And, it was

sort of an art comic, like something Raymond Pettibon or Gary Panter might do.

Those are probably the closest analogues.

What was important in their art is that

they were focusing on daily life. It was very different from the mainstream

comics scene in Poland in the 90s, because most of those comics were, you know,

fantasy. Some fantastic alternate worlds, but not our daily life, which looked

boring in comparison. But, I responded to these comics, because they presented

that boring daily life as something very attractive and strange.

|

Fig. 8. Maus (2001-2015)

by Wilhelm Sasnal, with art removed from (the Polish translation of) Spiegelman’s

page. |

Most of them are autobiographical. Sanal

also focused on history, the Holocaust, Communism, all that. He even did a

project inspired by Maus in Bielsko-Biała, a Polish town in which

Spiegelman’s Maus partly takes place, where Artie’s parents are from. On

this one page of the comic, he erased all the characters, leaving only the

speech bubbles. And it’s a very dramatic moment, which really happened in that

town, and it was mounted on the wall of one of the buildings where the action

happened. It’s like a found footage comic project. Also site specific, because

the place is important. He also creates a series of paintings inspired by Maus,

the interiors of the concentration camp without any characters.[xx]

|

Fig. 9. Vol. 2 of Marzena Sowa’s

graphic memoir, Marzi, published in 2006. |

|

Fig. 10. Woynarowski’s The

Dead Season (2014). |

JW: Before, you were

talking about climate change and all these things related to the Anthropocene.

It made me think that my graphic novel, The Dead Season, is also dealing

with that. It’s also about the ecological crisis, as well as my childhood. It

combines different visions of apocalypse, including climate change and nuclear

catastrophe. But, it’s also about a pandemic, a Coronavirus. It was created in

2014, so before the pandemic. You could also relate this theme to a recent

popular trend in Polish visual arts, which are all these motifs related to death

and undead creatures. To the fuzzy line between life and death.

Related to that, and getting back to

superheroes, Tim Burton’s movies about “Batman” were a great inspiration for

me. Especially “Batman Returns” (1992), which was more creepy than the first

film. I was influenced a lot by the character of Scarecrow. I drew Scarecrow a

lot as a child; it was one of the main motifs in my early art.

[i] Funded by the

Soviet Union, the socialist realist suburb of Nowa Huta rose up after World War

II. The Communist authorities saw it as a showcase city, where 100,000 workers

could live the good life thanks to central planning. Today, the district has

residential areas, arts, and cultural centers. It forms quite the contrast to

the familiar “gothic” Kraków that attracts more tourists.

[ii] Zdzisław

Beksiński (1929-2005) was a Polish painter, photographer, and sculptor, a

master of dystopian surrealism. Some took his paintings as expressions of

horror and despair under Communism. In 2016, a permanent exhibit of Beksiński’s

works opened in the Nowa Huta Cultural Center.

[iii] The neon

yellow-green statue, “Fountain of the Future” (a.k.a. Pissing Lenin), by

Małgorzata and Bartosz Szydlowski, was unveiled during Kraków’s 6th Grolsch

ArtBoom Festival in 2014. It was meant as a tongue-in-cheek replacement for a

mammoth and much-hated Communist-era Lenin statue in Nowa Huta’s central

square, which was removed in 1989. After the festival, “Fountain” was moved to

the rooftop terrace of the Utopia Home (Dom Utopii) International Empathy

Center, a multi-use facility in Nowa Huta.

[iv] Visitors and

residents of Prague will often run into the humorous public art works of Czech

artist, David Černý (b. 1967). These include “St. Wenceslas” (2000), showing

the medieval Czech king riding atop a dead, upside-down horse (hanging in the

Lucerna building) and “Babies on the Tower” (2001), mounted on the Žižkov

Television Tower.

[v] Russian

conceptualist art duo, Komar & Melamid, made up of Vitaly Komar (b.1943)

and Alexander Melamid (b. 1945), spearheaded the Sots-Arts movement in the late

Soviet Union.

[vi] “Torment” formed

the first story arc in Todd McFarlane’s mega-hit, Spider-Man (1990).

[vii] Barry

Windsor-Smith’s story arc, “Weapon X” (on Logan/Wolverine of the X-Men),

appeared in Marvel Comics Presents #72-84 (March-September, 1991).

[viii] See, “Accident

Prevention Regulations on the Use of Wood-Planing Machines” in Franz Kafka: The Office Writings. Corngold, S., et

al., eds. Princeton University Press, 2009.

[ix] French writer,

Michel Carrouges, coined the term, “Bachelor Machines,” for the many

hypothetical contraptions and mechanical art pieces which emerged in the wake

of the Industrial Revolution, which, among other things, he took as supreme

examples of Freudian sublimation. He derived the term from Marcel Duchamp’s “The

Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors” (The Large Glass) (La mariée mise à nu

par ses célibataires, même, 1911-25). In a famous 1976 Paris exhibit, Harald

Szeemann brought some of these fictional works into the physical plane. See Chapter

4 of Constance Penley’s The Future of an Illusion: Film, Feminism, and Psychoanalysis (1989).

[x] French artist, Francis

Picabia (1879-1953), was a major figure in the Dada and non-objective painting

movements of the early 20th Century.

[xi] Tadeusz

Baranowski (b. 1945), a pre-eminent Polish comics artist, started publishing

his work in 1975. Among the most famous are A Journey on the Dragon

Diplodocus (Podróż smokiem Diplodokiem, 1986).

[xii] Jan Lenica

(1928-2001), a major Polish cartoonist, graphic artist, and animator, directed

the classic, “Labyrinth” (Labirynt, 1963).

[xiii] Award-winning

animator, Jerzy Kucia (b. 1942), known for “The Return” (Powrót, 1972) and “Parade”

(Parada, 1986), teaches in the Academy of Fine Arts Animated Film Studio in

Krakow.

[xiv] British animation

duo, the Brothers Quay, made up of Stephen and Timothy (both b. 1947), have

shown a lot of Eastern European influence in their award-winning works, e.g., Street

of Crocodiles (1986), based on a short story by Polish author, Bruno

Schulz.

[xv] Surrealist Czech

animator, Jan Švankmajer (b. 1934), influenced generations of artists in his

home region and beyond, with remarkable works, such as “Dimensions of Dialogue”

(Možnosti dialogu, 1983) and “Little Otik“ (Otesánek, 2002).

[xvi] Polish film

auteur, Walerian Borowczyk (1923-2006), produced porn-inflected art house

cinema. He also dabbled in surrealist animation.

[xvii] Jakub Mikurda

& Jakub Woynarowski. Corpus Delicti. Stowarzyszenie Nowe Horyzonty,

2013. See, also, “Animated Bodies: A

Conversation Between Kuba Mikurda and Jakub Woynarowski.” Boro, l’île

d’amour : The Films of Walerian

Borowczyk. Kuc, Kamila, et al., eds. Berghahn Books, 2015.

[xviii] Love Express: The Disappearance of Walerian Borowczyk

(Love Express. Przypadek Waleriana Borowczyka, d. Kuba Mikurda, Poland/Estonia,

2018).

[xix] While primarily

known as a successful Polish painter, Wilhelm Sasnal (b. 1972) has also

produced cartoons for the periodicals Machina and Cross-Section

(Przekroj).

[xx] Maus

(2001-2015). Sasnal mounted the image on the exterior wall of the Gallery BWA

in Bielsko-Biała. He had intended to mount it on a wall of the Museum of

Technology, which was formerly a factory owned by the Spiegelman family.

Permission was denied. The controversial Polish translation of Maus

first appeared in 2001. Some objected to Spiegelman’s depiction of Poles as

pigs, among other things.

[xxi] Marzena Sowa (b.

1979) published the graphic memoir series, Marzi, with art by Sylvain

Savoia, starting in 2005.

[xxii] Szpilki was

published from 1936 to 1994, with some interruptions (e.g., martial law

restrictions in the 80s).

[xxiii] Jan Sawka

(1946-2012) produced anti-government prints, paintings, and cartoons in Poland

and emigrated to the U.S. in the 1970s.

[xxiv] Published in The Believer. No. 52 (March 1, 2008). https://www.thebeliever.net/anna-karina-and-the-american-night/.

________________________

José Alaniz is a professor in the Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures and the Department of Cinema and Media Studies at the University of Washington, Seattle, and has published academic books on Russian/Eastern European comics and other topics.