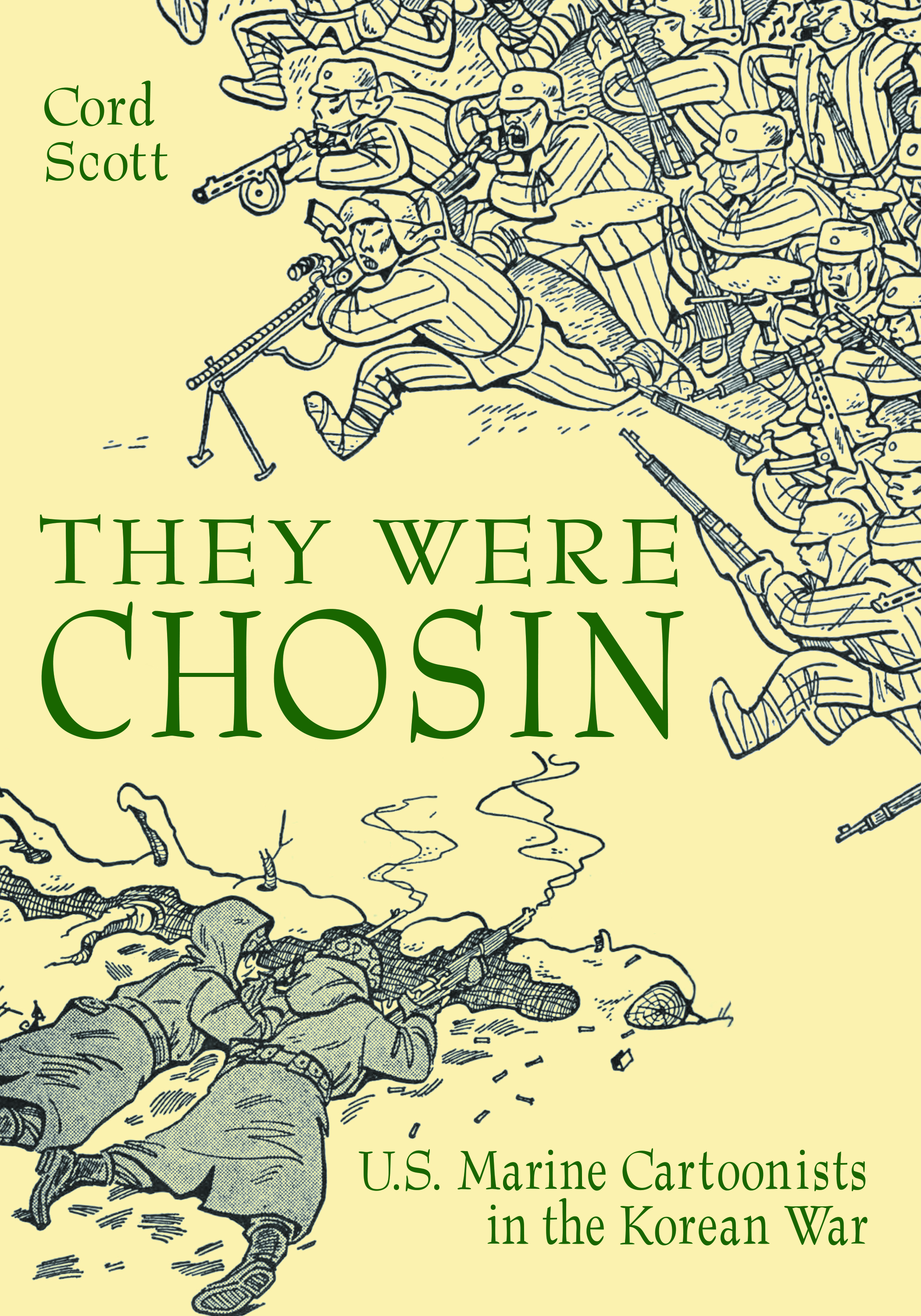

Cord A. Scott. They Were Chosin: U.S. Marine Cartoonists in the Korean War. Quantico, VA: Marine Corps University Press, 2025. 234 pp. Free epub and pdf. ISBN #: 979-8-9878492-0-0. https://www.usmcu.edu/Outreach/Marine-Corps-University-Press/Books-by-topic/MCUP-Titles-A-Z/They-Were-Chosin/

They Were Chosin, like Cord Scott’s previous work, The Mud and the Mirth, serves to highlight the cartoons produced by and about members of the U.S. Marine Corps. Published by the Marine Corps University Press, it blends reprinted material with visual analysis and histories of significant creators, offering insight and depth about the Marine Corps’ wartime publications. This time, Scott turns his attention to the illustrations from the Korean War, focusing in particular on Norval E. “Gene” Packwood’s Leatherhead: The Story of Marine Corps Boot Camp and Leatherhead in Korea.

Available both in print and as a free epub and pdf from the Marine Corps Press, They Were Chosin showcases some of the material produced by, for, and about the Marines during wartime. This, alongside Leonard Rifas’ 2021 book, Korean War Comic Books, and Paul S Hirch’s, Pulp Empire, continues to serve as correctives to tendencies to ignore wartime comics after 1945, especially those of America’s “forgotten war.”

The majority of They Were Chosin concentrates on the art of Packwood, who produced two books about (and for) the Marine Corps in Korea. While Scott also addresses other cartoonists of the period, and comics about the war, these are largely relegated to footnotes. Yet, at the same time, Scott gives the reader little information about Packwood, instead, choosing to devote the vast majority of the book to reprints of his cartoons, particularly those from Leatherhead and Leatherhead in Korea.

The ultimate strength of Scott’s work is in the reproduction of this material. The book contains 134 images, which are printed clearly, and in high fidelity across 234 pages. A mixture of color and black-and-white illustrations, They Were Chosin demonstrates the admirable commitment by the USMCU to improving on The Mud and the Mirth, their first foray into comics scholarship. The cartoons in The Mud and the Mirth were often difficult to parse and read, owing in part to their reduced size and the placement of multiple cartoons and comic strips together, which meant that text in the cartoons was almost unreadable. By contrast, They Were Chosin is printed in an oversized 7x10 paperback format, and the full-page illustrations are much clearer. This adjustment is a marked improvement over the format of the first book.

At the same time, there are still some stylistic kinks to work out. The first is that, as an image-heavy book, chapters include only a minimal amount of analysis, with brief snippets of text intercut with large chunks of reproduced cartoons. Chapter Two (“Norval Packwood and the Creation of Leatherhead”) features only four pages of text to eighty-eight images, with text on pages 15, 16, 74, and 76. Likewise, Chapter Seven (“The Modern Era,” which references British cartoons about the Korean War) is only three pages long, includes two half-page illustrations, and contains barely enough text to fill a single page. This leaves scant room in these chapters for historical contextualization, biographical information about creators, or analysis. Perhaps the best option here would have been for this book to be released with fewer images alongside full reprints of Packwood’s Leatherhead: The Story of Marine Corps Boot Camp and Leatherhead in Korea, allowing Scott room to dig deeper into these cartoons and their meaning. While the press makes clear that this is “not meant to be a definitive visual history of the Korean War,” further exploration and writing about these cartoons within this monograph seems necessary to avoid it being anything more than a brief primer. Scott’s brief history on the course of the war, intended for readers who may be unfamiliar with the broad strokes of the conflict, is an excellent example of his ability to blend military and cultural history and could easily have been expanded on to tell a more complete historical story of the Marine Corps in Korea. This is ultimately an area where The Mud and the Mirth set a standard that They Were Chosin fails to live up to.

Ultimately, the lack of broader analysis holds They Were Chosin back from being an essential history of the Korean War’s military comics, limiting its reach. Instead, it seems to set up future works on the illustrations produced by, about, and for the Marines during the early Cold War. While it will invariably be an important read for anyone interested in the comics of the Korean War, it feels like a missed opportunity to write the definitive account of the Marine Corps’ comics during the period, and tell a larger and more substantive tale.

A version of this review will appear in print in IJOCA 27-2.