by Mike Rhode

Randy Scott has left the building.

Michigan State University Library's Comic Art Collection is without his guidance and leadership for the first time in decades.

Halloween (October 31) was the long-time librarian and curator's last day in the collection he built. Since 1973, for almost 50 years, Scott helped the collections of comic books grow to the largest collection in the world. The collection also has massive amounts of comic strips, topical files, and material related to editorial and animated cartoons.

My friend Randy is heading for a retirement which includes a new sailboat, and the possibility of again reading comic books for fun. I'll miss working with him. For the past 2 decades, I've been scouring library sales and flea markets in an attempt to stump him with material the library didn't have, and which he may not have known existed. I think I did pretty well, and I'll miss our monthly calls about what I've found and gotten ready to mail to Michigan for the use of future researchers (especially giveaways from local comics stores). In the years to come, as more and more published material is digitized, I'm betting the grey literature and Pop Culture Vertical Files of information become more valuable.

17 years ago, Scott wrote about his career for IJOCA 7:2 (Fall-Winter 2005) in "Beginnings and Landmarks: The Comic Art Collection at the Michigan State University Libraries and My Career." Here is his article:*

The "beginning" for me was 1971, when I read the book All in Color for

a Dime (New Rochelle, NY: Arlington House, 1970). In the introduction, Dick

Lupoff and Don Thompson announced that theirs was only the second book

about comic books "that did not strive to condemn and destroy its topic"

(p.14, 1997 ed.). Even then, when I was a college undergraduate and working

in an early comic book shop, this seemed like an incredible insult to the comic

books I had grown up reading and cherishing. "Academia" or society at large,

or whoever was responsible for getting books published, was really out of

touch.

A little context might help. I was then a recovering student radical, having left

college for a while to argue for regime change in the streets, as it were. I learned,

for example, that biting an officer of the law will get his attention,

but that they don't taste good. Also I learned that six months in

jail is no fun. I was hired, fresh out of jail, by the Curious Book Shop

in East Lansing, in June 1971. Ray Walsh, the proprietor, had been a

fellow student worker in the Michigan State University Libraries a

few years before, and his science fiction specialty shop

looked like a good place to hide from the law. The store grew into a

real antiquarian book shop, and I became the comics guy, because that's

what the store needed. It was a kind of boot camp. For two years I

sorted, graded, priced, and sold comic books under the guidance of Walsh.

With Ray, I attended two Triple Fan-Fare conventions in Detroit and ran the

Curious tables. We were in on the beginnings of the network of stores that led

to the direct market for comics. It was a boom time for comics collecting, and

I started reading and collecting comic books myself.

This intense activity was a refuge from serious notions of smashing the

state, but I was still looking for ways to change the world. The evil empire of

comics-rejecting English departments seemed like a good place to start. I

decided to take the situation in hand, get out there and write important books

and, you know, do stuff. In those days that counted as a plan of action. One

of the shop's customers, Professor Russel Nye, had just published his

groundbreaking The Unembarrassed Muse (New York: Dial Press, 1970). He

was going to be my role model, and I started taking English classes. After a

couple of graduate courses in English, it turned out that that literary analysis

was not my metier, but my determination was not really quenched.

In 1973, armed with a Bachelor's degree, I left the minimum wage world

of the comic shop and joined the Michigan State University Libraries. The

research material for The Unembarrassed Muse had already been deposited in

the Libraries, and that included 6,000 comic books for Nye's chapter on comics.

I was still reading and collecting comic books. It occurred to me that a logical

reason for the lack of scholarly work on comic books might be a lack of

available collections of comic books. This seemed like a useful insight at the

time, though, of course, the more central reason for a lack of university

scholarship was that one couldn't expect to get tenure in a university by

writing about comic books. Still, I was sustained by the idea that adequate

collections were required to advance the study of comic books past the

nostalgia stage, and it wasn't a wrong idea. I discovered that the library

valued my bookstore talent for putting things in order, physically and logically,

and decided that doing so for comic books would be my contribution.

It turned out that the Library wasn't just going to let me realign its

priorities single-handedly. I was only a typist, and a lot of typing needed to be

done. Still, I was a good typist and was soon trusted to volunteer to work on

the comic books on my own time. I spent two years of lunch hours working on

the comics collection, helping sort it, organize it, and stamp it with ownership

stamps for security. When it became clear that the overall status of the comics

collection wasn't going to change much through this effort, I went away for a

year to Columbia University for a Master of Science in Library Service. Upon

my return, this Ivy League degree got me a job typing again, though this time

it was as the German-language cataloger. I mastered the tools, cleared away

the German books, and dove into the comics. Students in library school ask

me today how they can get library jobs working with comics. There is no clear

path, but, in general, libraries hire for certain mundane skills and qualifications.

For me it was excellent keyboarding and a good grasp of written German.

The first after-hours task I undertook as a professional was to index all

the stories in all the comic books. I started, in July 1974, typing index cards for

every story. This turned out to be a bigger job than I expected. When I quit

typing cards, in October 1983, there were 74,000 of them. They are in my

basement. During most of this card-typing time, I was also a member of APA-I,

the comics indexers' amateur press association. This communication with

other comics indexers, particularly with Jerry Bails and Gene Reed, was

important in refining my style of indexing. My card index, much of it converted

directly from the card file, is visible today online as story title entries in the

Reading Room Index. Next, I decided that the comics should be cataloged by

the library into the national computer database, OCLC, which came to our

library in 1975. As a librarian I had direct access to the computer system, and

could decide for myself to some degree what to catalog. This was a more

visible and more controversial project. On the one hand the international

presence of our cataloging started to bring positive attention from remote

scholars, but on the other hand the sight of me working so single-mindedly on

comics was galling to more than one library administrator. I hoped that attitude

would change, and it has, though I still can't claim that the library has let me

realign its priorities. A general seepage of respect for comics has been coming

into the academic world over the past three decades, which I hope our collection

has helped to promote, but which has certainly helped elevate the in-house

status of the collection.

In the early 1980s, I made a pilgrimage to San Francisco to see Bill

Blackbeard and the San Francisco Academy of Comic Art. Well, actually, it

was a family visit to Berkeley, but I squeezed in a visit with Mr. Blackbeard.

Seeing the SFACA collection, and hearing Bill's story of the rescuing of all

those newspapers slated for pulping because they were replaced by microfilm,

was an inspiration. It is really possible to make a difference by getting down

and working 20 hours per day on something for years. It doesn't hurt if it's

something nobody else is doing, and that most people think is a little odd.

Sorry for putting it that way, Bill, but you're one of my role models. That the

Blackbeard collection has ended up at The Ohio State University is a joy.

Because of my lifelong interest in languages, from the beginning, I planned

to make this an international collection. I had no idea, in 1971, what the world

of comics beyond our borders might look like, but it seemed exotic and

interesting. Mexican comics have been available off and on in our local

community, and I made a practice of buying as many as possible even before

I came to work at the Library. These little purchases, plus a habit of begging

friends and relatives to bring back comics as souvenirs from their travels,

soon began to add up to a useful collection. The Latin American collection,

with the help of a few solid donations and some purchases in recent years,

now stands at about 5,000 items. A similar dynamic has happened with the

Japanese collection, currently at 4,500 items. These are still very modest

collections, but they are outstanding for a North American library.

|

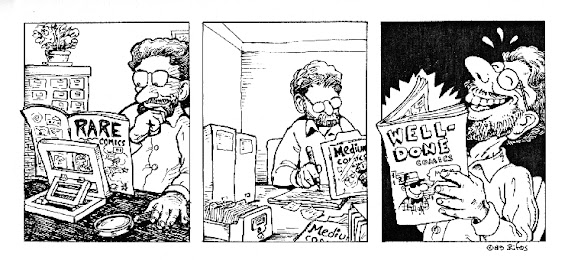

Leonard Rifas' drawing of himself in1989 visiting the MSU Comic Art Collection.

|

The first big breaks for the growth of the Comic Art Collection happened

in the very early 1980s. First came the gift of over 1,000 Golden Age comic

books by a collector named Jim Haynes. He saw my letters in The Buyers

Guide for Comic Fandom and contacted us. Before that, our comic books

were no older than about 1963, but after that, we began to see possibilities for

a more complete collection. The microfilms privately created by Jerry Bails

were our next big step. Jerry Bails is another one of those individuals who

have made an incredible difference just by working 20 hours per day for

decades on the task of preserving comics. The films are in black and white,

and the quality is variable and mostly not so good by today's standards, but

these films are priceless. For the Library, having 200 reels of miscellaneous

Golden Age comics, plus a thousand hard copy Golden Agers, meant that by

the middle of the 1980s, we could claim the beginnings of a credible research

collection for older U.S. comic books. That was a landmark.

Catherine Yronwode, Dean Mullaney, and Eclipse Comics were the next

big event, again in the early 1980s. Even before they met, both Yronwode and

Mullaney had been sending us boxes of stuff, as had several comics fans all

around the country. When Eclipse Comics formed, the MSU Libraries gradually

found itself on the "comp list" not only of Eclipse, but of nearly every other

publisher. Cat just counted the library as one other staff members, and when

multiple copies of an exchange publication from any publisher came in, one of

them went into a box for the library. This went on for several years and began

to include European publishers as well. This was more than substantial; actually,

it was overwhelming. Several year-long cataloging projects were done, though

without additional staff or funding. By the middle of the 1990s, when Eclipse

went out of business, the library's collection of American 1980s and 1990s

comic books was relatively complete and well-organized. The shelves were

full, the Special Collections Division was bursting at the seams, and donations

kept coming in from fans and collectors.

The reader will notice that little mention has been made to this point of

the spending of money on this collection. We did, actually, purchase the

microfilms from Dr. Bails, in several increments supported by one-time funds.

The comics collection had no regular budget for most of this time. By 1995,

however, we had a budget that allowed us to spend several hundred dollars

per month, and that is when Horst Schroder comes into the picture. Dr. Schroder

is a German comics fan and the publisher of the Epix Comics line in Sweden.

He contacted Peter Coogan, a graduate student at Michigan State University

at the time, with an offer to sell his collection. It's a long story, but in the end,

MSU bought the European part of his collection, 11,000 items, and they arrived

in the summer of 1995. Coincidentally, the Library was able to finance the installation

of compact shelving in the Special Collections Division, so that

the boatload of comics from Sweden had space to rest. There followed three

years of furious cataloging, entering all these items into the library data system

OCLC, or WorldCat, as researchers know it today, and into our local on-line

catalog. Not only, it should be noted, did the Library buy these new motorized

shelves at great expense, but the library has consistently supported the

collection with preservation supplies (acid-free enclosures and mylars) and

expensive deacidification treatment for these "free" comic books.

By 1999 the bill for the European comics was almost paid off, and it

seemed like we had reached a state of balance between scope and depth. The

collection had over 150,000 items from every part of the world, and donations

of American comic books were still accumulating rapidly. For now, the American

collection is satisfactory, and I can estimate based on the "hit rate" of what

people ask for, that we have about 60 percent of a complete collection. As we

learn more about "foreign" comics, however, it becomes clear that these

collections are still very modest compared to what is possible. Ohio State

University has taken the lead in collecting Japanese comics, and so, for MSU,

the European and Latin American collections have come into focus. We have

started spending our little bits of money to upgrade these collections, and I

have begun studying and traveling to help do this more intelligently.

As for the general status of the collection, the goal has always been to

use the tools of library tradition that have been established by the American

library community, so that successors to this job will be working in ways for

which there is standard training. I would not expect a librarian who came after

me to be a fanatic about comics, and, in fact, would prefer one who is first

competent in the organization, preservation, and servicing of fragile cultural

materials. Speaking both as a library professional and a fanatic (that delicious

new word otaku comes to mind), I must admit that there is a possibility of

combining these traits. I have roughly one more decade to work on this project

before I retire. If there are any lifelong collectors out there who want to place

collections in state-of-the art conditions in terms of preservation, organization,

and research context, you all should contact me pretty soon. It may seem like

200,000 comics items, which is what we count today, is such a big collection

that other collections would just be duplications. This isn't so. We don't have

any EC comics, for example. We have very few giveaway comic books, and

our runs of war genre comics are very weak. We have practically no Philippine

komiks. In a way, our collections are mostly accumulations, because they

have been acquired almost without money. We are the best in many areas by

default, because there are so few other collections in those areas. I will surely

postpone my retirement if some really interesting collections come in, because

I am still just as determined as I was in 1971.

Randy may or may not be as determined as he was in 1971, or 2005 for that matter, but the field owes him an immeasurable debt which we can never truly repay. Randy's leadership (along with OSU's Lucy Caswell and others) preserved the history of art form that matters to scholars of the field and all readers of IJOCA.

*the second two paragraphs were omitted in editing, and replaced on 11/3/2022.