Exhibits in Angouleme are generally comprehensive, overwhelming, crowded and only in French. Mr. Heng has braved the crowds to provide us with snapshots of the Festival so our readers can get a general impression. Catalogs for the major exhibits are on sale, but often sell out during the show. By Saturday it will be almost impossible to move through these galleries.

Articles from and news about the premier and longest-running academic journal devoted to all aspects of cartooning and comics -- the International Journal of Comic Art (ISSN 1531-6793) published and edited by John Lent.

Friday, January 31, 2020

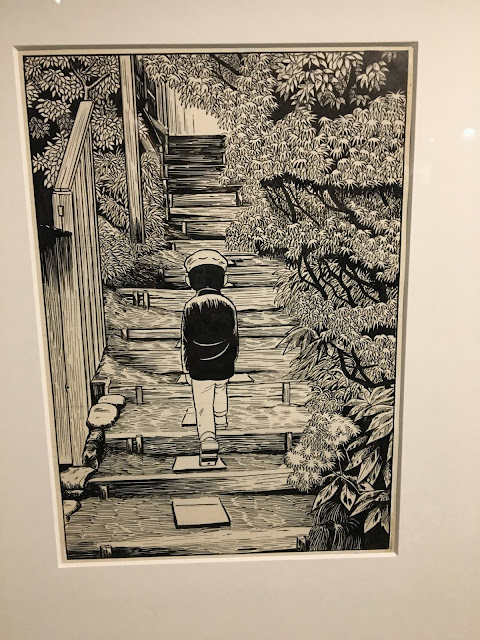

Angouleme 2020 in Photos #1: Yoshiharu Tsuge, 'être sans exister' exhibit

By Gerald Heng

Exhibits in Angouleme are generally comprehensive, overwhelming, crowded and only in French. Mr. Heng has braved the crowds to provide us with snapshots of the Festival so our readers can get a general impression. Catalogs for the major exhibits are on sale, but often sell out during the show. By Saturday it will be almost impossible to move through these galleries.

Exhibits in Angouleme are generally comprehensive, overwhelming, crowded and only in French. Mr. Heng has braved the crowds to provide us with snapshots of the Festival so our readers can get a general impression. Catalogs for the major exhibits are on sale, but often sell out during the show. By Saturday it will be almost impossible to move through these galleries.

Labels:

Angouleme,

exhibit,

France,

manga,

online only,

Yoshiharu Tsuge

Thursday, January 30, 2020

Angoulème 2020 Exhibit Review: Yoshiharu Tsuge, 'être sans exister'

Yoshiharu Tsuge, être sans exister. Stéphane Beaujean, Léopold Dahan and Xavier Guilbert. Angoulème. Musée d’Angoulème. 30 January - 15 March 2020.

The Angoulème International Comics Festival continued its mission to consecrate an important mangaka with a major exhibition devoted to the life and work of Yoshiharu Tsuge. The exhibition was installed in the same space in the musée d’Angoulème that was reserved over the three previous years for similar exhibitions that elevated Kazuo Kamimura, Osamu Tezuka and Taiyo Matsumoto to the wider festival audience (and beyond). Être sans exister follows the template set out by those earlier exhibitions by intertwining biographic information with historical, industrial and cultural contexts to individuate Tsuge’s narrative and aesthetic style.

An

incredible collection of over 270 pages of original artwork, almost all

of it being displayed outside of Japan for the first time, provides the

visual support for the exhibition’s reconsideration of Tsuge’s place

not only within the history of postwar manga, but also his contributions

to the development of comics as an artform.

Close

readings of the displayed pages intelligently highlight how Tsuge

transitioned from his early commercial work (where his debt to Tezuka is

undisputed) toward a more personal individual style that used oneiric

narratives and open-ended endings to express his inner preoccupations

and demons. A highlight of the exhibit in this context is the

presentation of Tsuge’s surreal 1968 tour de force La Vis (translated in English as “Screw Style”), which is presented in its entirety by the original pages of artwork.

first page of "La Vis"

This artistic breakthrough hinted at a personal cost as Tsuge’s work began to incorporate darker, introspective themes that foregrounded the psychological toll that his characters endured within their rigid social environments. These autobiographic undertones informed Tsuge’s later travel narratives, which suggested a retreat from the constrictions that were plaguing the fragility of his personal life and mental health.

It is this very relationship between artistic expression, formal innovation and psychological intimacy that the exhibition illuminates to position Tsuge as a comics artist whose work deserves a thorough reappraisal. A handsome catalogue has been published by the festival that reproduces the entire text and images of the exhibition to serve as a fitting record of this living artist whose body of work reveals the personal hardship endured in a search toward a semblance of inner peace.

Nick Nguyen

All photos taken by Nick Nguyen

A version of this review will appear in print in 22:2, but the exhibit is currently open at Angouleme, France through the weekend.

Labels:

Angouleme,

exhibit review,

Japan,

manga,

Yoshiharu Tsuge

Book Review: Visible Cities, Global Comics: Urban Images and Spatial Form by Benjamin Fraser

Benjamin Fraser. Visible

Cities, Global Comics: Urban Images and Spatial Form. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2019. $30

paperback, $99 hardcover.

Benjamin Fraser. Visible

Cities, Global Comics: Urban Images and Spatial Form. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2019. $30

paperback, $99 hardcover.

In Visible Cities, Global

Comics: Urban Images and Spatial Form Benjamin Fraser takes an “urban

cultural studies approach to the medium of comics” (2019: 3). Braiding comics

theory alongside Marxist spatial thinkers such as Raymond Williams and Henri Lefebvre,

Fraser argues that “comics artists necessarily comment on the way social power

drives the structure of the city, resulting in the exclusion of certain groups

and certain ideas” (2019: 6-7). While Visible

Cities, Global Comics follows an increasing interest in the urban and

spatial aspects of comics, as seen in edited collections such as Jörn Ahrens

and Arno Meteling’s Comics and the City (2010) and Jason Dittmer’s Comic

Book Geographies (2014), it has the distinction of being the first

scholarly monograph on global urban representations in comics. The book theorizes

how cities are represented in comics and how urban geography is implicated in

the very structure of comics as an industrialized art form (Fraser, 2019: 217).

Fraser sees three important

points of connection between cities and comics: subject matter, artistic form,

and method of production. Explaining the importance of what he calls “an urban

contribution to an interdisciplinary phase in comics studies,” he says:

First,

the city becomes a privileged subject of comics. Second, the panel-and-gutter

structure of comic strips, in particular, reflects the way in which art was

impacted by tropes of linearity and rational planning that were themselves

synonymous with the urban form. Third, the mass production of comics showcases

its links with forms of industrialization that are urban in origin. (Fraser, 2019:

3, 7).

Fraser’s three-pronged

analysis is perhaps one of the book’s greatest contributions. He does not

merely analyze the visual representation of cities in comics, how “the city

becomes an iconic expression of modernity in comics” (Fraser, 2019:7). Fraser’s

analysis is both deeply formalist, attending to the geometrizing devices of the

comics page, and deeply materialist, tracing the historical contexts and

political economies under which comics creation, production, and distribution

become intertwined with urban logics. The book’s second significant

contribution is its global and temporal scope. The book comprises comics from

across the globe from the 18th century through the contemporary

moment, and Fraser carefully situates each comic within its unique geographic

and sociohistorical location. While Fraser himself notes that the book

emphasizes works that have already been translated to English, with the

exception of a few Spanish-language comics, its attention to global comics slightly

pushes the needle away from comics studies’ Anglophone emphasis and showcases

the importance of highlighting newly translated and non-English works.

Tracing the intersections of

content, form, and production, Fraser begins each chapter by offering a

theoretical framework for reading comics through a particular node of urban

cultural studies. He then provides a series of examples, examining each comics

artist somewhat chronologically and offering biographical and historical

context as necessary before moving into an analysis of their work. The first

chapter focuses predominantly on early comics, beginning with Hogarth and then

moving into the rise of comics alongside 20th Century print

journalism, that are “decidedly urban in orientation,” comics that represent

city spaces thematically and formally and engage urban readers (Fraser, 2019:

19). Where chapter one evaluates the representation of the city in comics, chapter

two interrogates the affective, interior effects the city has on the lives of

urbanites. It takes a Marxian approach to urban everyday life and evaluates how

comics artists employ human senses to resist the “dehumanizing forces that

pervade the modern city” (Fraser, 2019: 51). Chapter three critiques how urban

planning is used to solidify power and privilege and explores how comics

represent the material structures of the city as oppressive and limiting. Chapter

tour interrogates the relationship between architecture and comics and

evaluates how both construct the tactile, spatial experience of the city. The

fifth and final chapter highlights how discourses about danger, disease, and

death that inform our understanding of the city are fantastically depicted in

comics. Together, these chapters investigate how the structure of the city

reinforces patriarchal and normative social and state powers, the material

impacts urban space has on the lives of urbanites, and how these dynamics get

represented, questioned, and critiqued in comic narratives (Fraser, 2019: 217).

Throughout the book, Fraser

maintains a commitment to emphasizing the material conditions of the city and

comics production. For instance, the second chapter traces how the linear

structure of modern urban planning coincides with the rise of mechanized

industrialization—in short, how “capitalism survived throughout the 20th

Century by producing space in its image” (Fraser, 2019: 52, 54). In this

chapter, Fraser argues that Daishu Ma’s Leaf (2015) uses color and

visual splendor to illustrate the Marxian premise that the human senses, such

as pleasure and curiosity, can resist capitalism’s alienation (Fraser, 2019:

89). Perhaps the book’s most salient example of how comics intertwine with the

material conditions of the industrialized city is Fraser’s analysis of Joost

Swarte’s The Comix Factory (1980) in the fourth chapter. Swarte’s single panel image, which was

designed especially for the cover of RAW #2, illustrates how comics

production is intimately connected to the structure of the city through its

visual density, verticality, and graphic excess (Fraser, 2019: 141-143). Visible Cities, Global Comics bursts with examples of how comics are

imbricated in the development of the city and its investments in

industrialization and global capitalism, yet Fraser avoids straying into

abstract musings about the formal “architecture” of comics that are devoid from

a materialist base. As he makes clear, “It is important to understand

that artistic representation is always tied to the material world in which we

live” (Fraser, 2019: 12). Fraser’s Visible

Cities, Global Comics: Urban Images and Spatial Form is expansive in scope and offers a significant contribution to both

urban cultural studies and comics studies. Ultimately, the work encourages comics

scholars to move beyond mere visual representation in their analysis and to consider

the material conditions under which comics are produced and how processes of

alienation, industrialization, and power manifest themselves in the formal

structures of cities and comics.

Maite Urcaregui

A version of this review will appear

in the 21:2 issue in the fall of 2020.

Maite Urcaregui is a doctoral candidate

in the Department of English at the University of California, Santa Barbara.

Maite’s research investigates how multiethnic American authors participate in and

problematize convenient discourses of citizenship, nation, and identity in

their literature through strategic deployments of visual elements. Her work is

forthcoming in The Routledge Companion to Gender

and Sexuality in Comic Book Studies >Gender and the

Superhero Narrative (University Press of Mississippi, 2018).

Wednesday, January 29, 2020

Introduction: Exhibitions of the 47th Angoulème International Comics Festival

2020 marks the 10th consecutive year that I’ve attended the Festival International de la Bande Dessinée à Angoulème, and each year there has been a progressive intensification by the organizers with respect to the programming. This 47th edition of the festival does not disappoint: with over 14 exhibitions and more than 350 events on the official schedule, it is a daunting task to do justice to the entire scope that takes place over the four densely packed days.

I’ve contributed some exhibition reviews of the Angoulème International Comics Festival for previous issues of IJOCA so this year, Exhibitions and Media Reviews Editor Mike Rhode has generously offered to let me experiment with the IJOCA blog. Over the course of the four and half days that I am present in Angoulème, I will cover as many of the exhibitions that are scattered throughout this small medieval French city as I can, posting photos and my immediate impressions and observations on this blog. This way I hope to capture an in situ record of the exhibitions in their original presentation context, since many of them have a life span that does not extend beyond the festival itself. These blog posts will then serve as the basis for an expanded review that will find a home in a future print edition of IJOCA. So fingers crossed that this experiment will be a successful one, and that I’ll have the strength and perseverance to bypass the crowds (which will apparently include an appearance by the President of the French Republic Emmanuel Macron himself!) to actually be able to cover the exhibitions.

-Nick Nguyen

Thursday, January 9, 2020

Exhibit review: Marie Duval: Laughter in the First Age of Leisure

|

| Promotional image provided by R. Sabin |

The Society of Illustrators’ Museum of

Illustration is currently hosting an exhibit devoted to the works of Victorian

cartoonist, Marie Duval. Duval pursued several careers during her life,

including actress, author and cartoonist, but this exhibit focuses on this last

pursuit, which made Duval one of the early female cartoonists in Europe and an

important figure in the field. Born Isabelle Émilie de Tessier, Duval worked

during the 1860’s to 1880’s using a number of different noms de plume,

including both male and female names.[1]

In part for this reason, her work has not always had the scrutiny and study of

which it may be worthy. This touring exhibit, which was created by Central

Saint Martins and the University of Chester with additional support from the London

Library and the British Library, seeks to introduce her work to a wider

audience.

Featuring slightly more than two dozen

examples of Duval’s cartoons, the exhibit offers a nice overview of her work.

Much of Duval’s art appeared in a publication called Judy or the London Serio-Comic Journal,[2]

and more than half of the pieces in the exhibit are taken from this

publication. The examples of her cartoons for Judy show Duval’s style, which often featured exaggerated features

and expressions on human and animal characters alike. Her works touch on

several topics, mostly related to trends and social commentary and almost

entirely from a humorous point of view. As an example, one of her comics

entitled “Rinkophobia: A Passing Fancy” pokes fun at roller skating and the

injuries it can cause. Though the vast majority of the works are done in black

and white, there are two color works included in the exhibit.

Perhaps of greatest note amongst her works are her Ally Sloper cartoons. These comic strips gained a great deal of popularity and she produced enough to be published in several volumes.[3] The exhibit includes several examples of these works which show the types of subject she covered in the strips and how the style of her art for these strips differed from her other artwork and, to some degree, from one another.

The exhibit is primarily made up of

reproductions, but most are done in a manner that makes the artwork’s place in

the larger publication clear. Unfortunately, the exhibit does not have clear

labels for each of the works, which would be helpful to offer more context and

also to make it easier for researchers to find the items for further research.

In addition, though some of the items are dated, several are not, making it

difficult to place them in the arc of her career without outside information.

However, despite these limitations, the exhibit is a nice introduction to the

work of a Victorian cartoonist who likely deserves greater acclaim than she has

received to date.

The exhibit and the related Marie Duval Archive (http://www.marieduval.org/), which was created by the same group of scholars, were made possible by an Arts and Humanities Research Council UK grant. For those interested in learning more about Duval, the Archive is an invaluable resource, which provides some basic background information about her and provides access to high resolution scanned reproductions of over 1,000 of her pieces ranging from 1869 to 1885 with more to be added in the future.[4] An additional resource is the book Marie Duval, edited by Simon Grennan, Roger Sabin and Julian Waite (Myriad, 2018, £19.99, ISBN 978-0-9955900-9-0). The exhibit was previously displayed at Berlin Illustrative and Guildhall Library.

Carli Spina

(This review was written for the International Journal of Comic Art 22:1, but this version appears on the IJOCA website on January 9 2020, while the exhibit is still open for viewing.)

[1] Simon Grennan, Roger Sabin and Julian Waite.

“About Marie Duval.” The Marie Duval

Archive. http://www.marieduval.org/about-marie-duval.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Simon Grennan, Roger Sabin and Julian Waite.

“Drawings by Year.” The Marie Duval

Archive. http://www.marieduval.org/drawings.

Labels:

Ally Sloper,

England,

Marie Duval,

New York City,

Victorian illustrators,

women

Wednesday, January 8, 2020

Exhibit Review: Comic Art: 120 Years of Panels and Pages

Comic Art: 120 Years of Panels and Pages. Sara W. Duke and Martha H. Kennedy, Prints and Photographs Division and Georgia M. Higley and Megan Halsband, Serial and Government Publications Division. Washington, DC: Library of Congress. September 12, 2019- September 2020. https://www.loc.gov/exhibitions/comic-art/about-this-exhibition/

Since I am friends with all four of the curators of the exhibit, consider this more of an exhibit overview rather than a review. Located in the historic Jefferson Building, the site of many fine exhibitions besides those of comic art, the Swann Gallery’s exhibits are always interesting and this one is no exception. The exhibit showcases highlights of the Library’s collection of comic art, meaning in this exhibit at least comic strips and comic books, including its very latest forays into collecting.

The exhibit is divided rather arbitrarily into five sections – “Early Years: 1890s-1920s,” “Mid-Twentieth Century: 1930s-1960s,” “Late-Twentieth Century and Onward: 1970s-2000s,” “Comic Books and Beyond: 1940s-2000s,” and “Webcomics.” Although the sections are clearly delineated on the website, this is less true for the actual exhibit except for the comic books which are displayed in cases in the middle of the gallery, and the webcomics which are on a screen by the exit door.

Taking the three original art sections first, there are some very good original cartoons on display, beginning in Early Years with the copyright drawing for the Yellow Kid, and originals from Winsor McCay, Frank King’s Gasoline Alley, George Herriman’s Krazy Kat, and some tearsheets from the Geppi Collection. The next section has a fine Batman & Robin page, a lovely Burne Hogarth original of Tarzan, and an early Peanuts original, although the Hulk page by Marie Severin has been shown too many times in recent exhibits. The latest section definitely plays into the interests of the two curators. There are two 9-11 pieces, one from Will Eisner and one from Alex Ross that were collected after that tragedy, a Sunday strip from local cartoonist Richard Thompson’s Cul de Sac, a page from the New Yorker's Chris Ware, items from women cartoonists Trina Robbins, Lynn Johnston and Marguerite Dabaie, and posters and prints from the Small Press Expo collection.

The comic book section is limited by both space and the difficulties in displaying bound printed matter, (as the Post Office classified comics when they were sent through the mail to subscribers). Again reflecting the interests of this sections curators, there are some rare pieces such as the recently-acquired All-Negro Comics no. 1 and DC’s World Best Comics no. 1, along standards such as a Disney issue of Dell’s Four Color Comics, EC’s Weird Fantasy, Lobo (an uninspired Western distinguished only by having an African-American hero), Harvey Pekar’s American Splendor, Mad no. 6, Twisted Sisters no. 1 and an fanzine among others. The Webcomics section just shows strips on a computer screen, made up from some of the electronic comics that the Library has begun collecting digitally including Ryan North’s Dinosaur Comics, Randall Munroe’s XKCD and Kate Beaton’s Hark! A Vagrant. It is nice that the curators are including this new form, but seeing them on a large computer screen in an exhibit gallery does not add anything to the understanding of the strips.

The exhibit will be switched out around February to preserve the paper items. In a small room next to the exhibit, Sara Duke’s selection of Herblock cartoons from fifty years ago is worth looking at, especially since the topics he drew and she selected are still problems and in the news.

Mike Rhode

(This review was written for the International Journal of Comic Art 22:1, but this version appears on both the IJOCA and ComicsDC websites on January 8 2020, while the exhibit is still open for viewing.)

Labels:

comic books,

comic strips,

exhibit,

Library of Congress

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)