By Barbara Postema

Angoulême:

49e Édition Festival Internationale de la Bande Dessinée, France, March 17-20, 2022. https://www.bdangouleme.com/

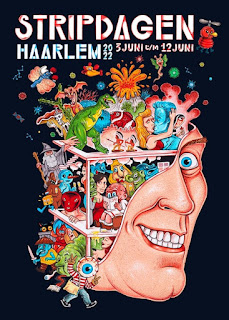

Stripdagen

Haarlem, Netherlands, June 3-12, 2022. https://www.stripdagenhaarlem.nl/

After several years of cancellations due to the COVID-19

pandemic, this year comics festivals are willing to give it a go again, and

exhibitors and attendees are eager to participate. Both of the festivals under discussion here were held in

a beautiful historic city at venues spread across the town center, showcasing

the city as a whole as well as the comics, and giving attendees room to wander

if they needed to escape the crowds.

The Angoulême festival, postponed

from its usual dates, was held in March for this once, where the spring-like

weather made for a nice change from the usual dreary weather conditions in

January. It was the 49th edition, already raising some anticipation for its

50th edition next year, for example with the selection of Julie Doucet for the

Grand Prix. Her selection ensures that the anniversary next year will be

historic in a number of ways—with only the third female Grand Prix winner

presiding, and with Doucet being the first Canadian to take the highest honor.

As usual the festival started with a

preview day for the press (March 16th), where exhibitions could be visited before

they were open to the general public, often with the creators and curators

present to provide commentary on the themes of the exhibits. Press day was much

appreciated this year in order to see exhibitions with fewer crowds around.

Programming for the press and comics professionals continued during the other

days of the festival, including the International Rights Market for negotiating

translations as well as adaptations to film.

However, the bulk of the events are

open to everyone (at the price of a day ticket), and this includes numerous

exhibitions, entry to the tents where publishers and creators are selling their

comics, kids events, and signings. I spent quite some time (and money) in the

tents Le Nouveau Monde and Espace BD Alternative, where small-press and

alternative publishers and cartoonists hocked their wares. These two tents

showed evidence of a few empty tables, signals perhaps that the move to March

meant that some publishers could not attend this year due to schedule clashes,

or perhaps that there were fewer international publishers and guests due to

continuing COVID-19 travel restrictions. This latter possibility was also

supported by the reported lack of Japanese guests and creators present at the

festival, a change from previous years. Other tents throughout the city

included Le Monde des Bulles, for the mainstream French comics publishers, and

Manga City, where manga-related publications could be found. There was also a

tent for the collectors, specializing in original art, special editions and

ephemera.

|

Chris Ware Exhibit

|

But perhaps the most important

aspect of the festival is the exhibitions. Every year there is a big exhibit

dedicated to the previous festival’s Grand Prix winner, who gets to showcase

their work. Chris Ware was elected for the Grand Prix in 2021 and at this

year’s festival he presented a retrospective of his work in the fairly intimate

space of the basement of Espace Franquin. The exhibition included many original

pages, some of which were astounding in their size, while also bearing witness

to the cartoonist’s careful and precise creative process. The show also

included various objects Ware had made, including wooden models made for

various family members to commemorate birthdays and anniversaries, as well as

some fully constructed versions of the paper models he included in the ACME Novelty Library books, though those

may have been assembled by someone else. The exhibit gave a nice sense of the great

care and attention Ware dedicates to his pages, though his creative process as

a whole remained mostly invisible.

|

| Loo Hui Phang exhibition in Espace Franquin |

The festival included two

exhibitions devoted to the writers of comics. One was in the same building as

the Ware exhibition: “Loo Hui Phang, Écrire est un Métier” shed a light on

Phang’s own writing process, but also that of many other people who write for

comics. Her exhibition also created awareness of the working conditions for

writers for comics, who often lack labor protections and are also shut out from

certain other avenues for making money in the comics world, such as selling

original art, even as they contributed to the characters or the story

represented in that art. She drew much needed attention to the precarious

nature of work in comics.

|

| René Goscinny exhibition in Musée d’Angoulême |

The other exhibition focused on writing for comics

put the spotlight on a writing superstar, René Goscinny, who wrote scenarios

for numerous series, of which Asterix

and Lucky Luke are probably the best

known in the English-speaking world. This exhibition, mounted in the Musée

d’Angoulême, provided an overview of Goscinny’s life and career while also

showing his creative process, which included research, coming up with the names

of characters (on of the key elements of the humor in the Asterix series), creating narrative sequences and writing a

synopsis. Eventually a full script including dialogue would go to the artist

(Albert Uderzo in the case of Asterix,

or Morris for Lucky Luke), and the

exhibition included many examples where the script pages were displayed

together with the finished art for the corresponding page of comics, shedding

light on a fascinating aspect of comics creation. Since comics writers tend not

to produce products that work well on museum walls, their contribution to

comics is sometimes easy to lose track of (as Phang’s exhibit also

demonstrated), but the Goscinny exhibition managed to make the highlight on

writing both illuminating and visually interesting.

|

| Shigeru Mizuki exhibition in Musée d’Angoulême |

The Musée d’Angoulême also hosted an

exhibition of the work of mangaka Shigeru Mizuki, on the occasion of his

hundredth birthday. The retrospective included original art from his

illustrations, his war comics and his horror comics, most notably the Kitaro series. The framed original art

was hung in a somewhat maze-like set-up, sometimes making for uncomfortably

close quarters with other viewers, but the large original drawings of Japanese

landscapes and creatures from folklore were stunning and fascinating

nonetheless. The festival included two further exhibits that focused on manga,

which I did not manage to view. I also skipped two exhibitions on comics for

children, since I was not familiar with the works and there was so much to see.

|

| Christophe Blain exhibition in Vaisseau Moebius |

Some of this year’s FIBD highlights

for me were two exhibitions held in the Vaisseau Moebius, “Christophe Blain,

Dessiner le Temps” and “Sous la Plume d’Aude Picault.” Blain is particularly

well known for period comics about pirates and cowboys, the series Isaac le Pirate and Gus.

Many original pages from these works were included in the exhibit, as well as

cover paintings, sketches, and originals from Blain’s many other comics and

from his sketchbooks. His inspiration from and homage to other media,

especially classic cinema, were a particular focus of the exhibition. Aude

Picault’s work was a revelation to me, as I was previously unfamiliar with her

work. She has made humorous slice of life comics about a nurse, as well as

travel diaries, memoir work, and several erotic comics. The exhibition of inked

pages, often from the stage before speech balloons and text were added, showed

off her light and elegant linework, well suited to her breezy narratives that

yet include touches of social commentary. |

Aude Picault exhibition in Vaisseau Moebius

|

The Cité BD, across the river from

the Vaisseau Moebius, is a set of converted 19th-century industrial buildings

which now house the BD museum and archives, as well as a large comics store. It

was buzzing with festival activities and crowded with school children on the

Thursday when I visited. I visited three exhibitions there that were not

specific to the Festival and were scheduled to run past the dates of the

festival, namely, “De Popeye à Persepolis: Bande dessinée et cinéma

d’animation”, “Baudoin: Dessiner la vie” and “La page manquante: Carte blanche à Wajdi

Mouad.” The Popeye to

|

| Wajdi Mouawad exhibition in Cité BD |

Persepolis exhibition was a large-scale survey showing

the cross-pollination between comics and animation over the course of more than

a century, including some attention to technical features of animation as well

as original pages and sketches by the creators involved. The exhibition on

Baudoin showed a retrospective of his entire oeuvre, featuring hundreds of

original pages that showcased the brushwork of his black and white art

beautifully. The exhibition created by Wajdi Mouad was the smallest of the

exhibitions in the Cité BD, taking up a single room only, but it was

conceptually the most immersive, since it was set up as an installation which

was meant to convey some sense of Mouad’s experience reading Tintin album L’Ile Noire in Lebanon, as well as his

experience with war and displacement to France, changing his perceptions of the

album over time. This small room provided a novel approach to comics-related

exhibitions, presenting a reader’s very personal experience with a book. Like the

Angoulême festival, the Stripdagen Haarlem was made up of exhibitions and

events spread across the heart of the city. The bi-annual festival had intended

to celebrate their 15th anniversary in 2020, but had to postpone and was

finally able to observe the festivities two years later,  |

| Small Press Award nominees in the Pop-Up Store |

still using the same

theme, world-building, and poster art by Dieter van de Ougstraete. Haarlem lacks

the year-round comics presence that Angoulême is able to sustain, thanks to

institutions like the Cité BD, so the festivities and exhibitions in Haarlem

were hosted by a range of more traditional museums and galleries. The

headquarters for the 10 days of the festival was a pop-up store which featured

festival merchandise, books by artists involved in the festival, and, an

important new addition to the festival, all the submission to the Small Press

Award, which made its debut at this year’s festival. The works were displayed

behind plastic in a large bookcase, but could be perused with the assistance of

the pop-up store’s staff. |

Rijkswachters X Stripmakers at Kunst Centrum Haarlem

|

While the Stripdagen lasted 10 days,

the main events took place during the two weekends bookending the festival.

Both weekends included lectures and workshops, while the opening long weekend

also featured markets where publishers, creators and antiquarians could be

found selling their wares. Unable to be there during the weekend, I attended

the festival on a weekday and took in six of the 20 or so exhibitions. The

decorated shop windows in the Kleine Houtstraat, around the epicenter of the

festival at the pop-up store, were a nice touch, and the other exhibits I

visited were all in close vicinity to the store. The venerable Teylers Museum,

the oldest museum in the Netherlands, hosted the Joost Swarte exhibition “Ode

aan het boek,” with all the included illustrations, sketches and pages related

to books in some way. There was a lot to see, but the close proximity of the

pages in a single room did not give the work much room to breathe. More of

Swarte’s work was on display in Galerie Kruis-Weg68, but unfortunately the

gallery had limited days.

|

Joost Swarte exhibition in Teylers Museum

|

|

| Marcel Ruijters exhibition at Museum Haarlem |

Some exhibitions nearby included

“Gevangen in Dromen: Wonen, Bouwen, en Beleven bij Marc-Antoine Mathieu,”

“Marcel Ruijters: Terug naar 1913”, “Rijkswachters x Stripmakers” and “Het

Kleinste Museum van Haarlem.” Marc-Antoine Mathieu’s oeuvre is impressive, and

the title, “Imprisoned in dreams” was evocative, but I found the exhibit a

little underwhelming, since while it captured the promised themes, the included

images and pages were photocopies pinned to walls and did not produce much new

insight into the artist’s thought or creative process. However, Mathieu’s work

has previously not been particularly well-known in the Netherlands, so perhaps

the exhibition will bring some deserved broader attention to the French

cartoonist’s work. The exhibition next door, devoted to Marcel Ruijters’

alternate world of 1913 proved more interesting, including original drawings as

well as sketchbook pages. The exhibition paid a lot of attention to the

world-building Ruijters put into his alternate history, so, like the Mathieu

exhibit, the show fit in well

|

| Haarlem’s smallest museum: SFF pocket covers |

with the theme of the Stripdagen. These exhibits

were to be found in the Museum Haarlem and ABC Architectuurcentrum

respectively. Close by, in Kunst Centrum Haarlem, was an exhibition that was

also a fundraiser. Just over 20 Dutch cartoonists had been invited to decorate

a small wooden figurine, made from packing crates used in the Rijksmuseum, to

capture the visual detail, style, or even the atmosphere of their work of

choice from the Rijksmuseum collection. The resulting figurines were on sale.

The most whimsical of the exhibitions I saw was to be found at the same address

as the Rijkswachters. This “smallest museum in Haarlem” took the shape of a

single shop window dressed with science fiction and fantasy pockets from the 1950s

and 1960s, all chosen for their colorful and imaginative covers that evoked the

contents of the novels in the most vivid and lurid ways possible, providing the

first hints at the world-building inside the covers. The books were all taken

from the collection of festival director Tonio van Vugt.

|

| Cor Blok exhibition in Noord-Hollands Archief |

The final exhibition I went to see,

and which I perhaps enjoyed most of the ones I visited at the stripdagen, was

also related to book covers. This exhibition, “De Wereld van Cor Blok,” was set

up in the building of the Noord-Hollands Archief, and showcased the work of a

Dutch artist and art historian who is best remembered for the covers he drew

for the Dutch editions of The Lord of the

Rings. The exhibition included some of his illustrations for Tolkien’s

work, as well as maps and drawings of his own fantasy world Barbarusië, collaged

and painted works that had never been exhibited before, and selections from his

one and only comics work, The Iron

Parachute, which Blok completed when he was 82 years old. This

retrospective had been intended to honor the artist in 2020, but the festival

and the exhibition were postponed due to the pandemic, and sadly Cor Blok died

in 2021 before the exhibition came about. The exhibition was fascinating to see

because it showed work in a great range of styles while also tied together by a

consistent character. In addition, Blok’s work also simultaneously had an old

fashioned quality harking back to the late 50s/early 60s when his Tolkien

illustrations first appeared while also feeling fresh and timeless.

The exhibitions of the Stripdagen were open for the 10 days of the

festival (or longer in some cases, like Swarte’s Ode to the Book). However, the

opening times were a little confusing, since especially the galleries kept

their own hours, mostly being open

during the weekends of the festival, but with more hit and miss times on

weekdays. As a result I found myself in front of a locked door when I tried to

visit “Schaduw over Holland,” a joint exhibit by Guido van Driel and Milan

Hulsing, drawing on their most recent graphic novels. Other exhibitions I had

to miss due to time constraints included “Storm in de Geest,” which featured

the world-building of the Pandarve, a fantasy world created by Don Lawrence and

Martin Lodewijk which can be enjoyed in the series Storm, and also “De

Klaagzang van de Verloren Gewesten,” an epic fantasy series set in a

medieval Celtic kingdom, written by Jean Dufaux and originally drawn by

Grzegorz Rosinski. By all accounts, these exhibitions capture the theme of this

year’s edition of the Stripdagen exceedingly well.

Both festivals offered a number of

attractive publications related to the year’s festival and exhibitions: the

FIBD has three published catalogs, for Goscinny, Mizuki, and Blain, as well as

poster sets. Stripdagen Haarlem offered a catalog for the Joost Swarte

exhibition “Ode to the Book”, a tie-in magazine called Wereldbouwers (world builders), which put a spotlight on the theme

of the festival and the various featured artists, as well as posters and prints

(some of them signed). These were available at the relevant exhibition venues

as well as at the pop-up store.

Barbara Postema is

Lecturer in English for Academic Purposes at Groningen University, a member of

the History in Comics research project, and an honorary research fellow at

Massey University New Zealand. Her book Narrative

Structure in Comics was published in translation in Brazil in 2018. She has

contributed work on narrative theory, wordless comics, and abstract comics to Image and

Narrative, the Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics,

and the International Journal of Comic

Art, as well as collections such as The

Routledge Companion to Comics and Graphic Novels, The Cambridge History of the Graphic Novel, and Abstraction and Comics. Dr. Postema is a

former president of the Canadian Society for the Study of Comics (CSSC/SCEBD),

and a current Member at Large of the Comics Studies Society (CSS). She is

co-editor of Crossing Lines:

Transcultural/Transnational Comics Studies, a book series from Wilfrid

Laurier University Press.

A version of this essay will appear in print in IJOCA.