Reviewed by Cord A. Scott, UMGC-Okinawa

Luke C. Jackson (w), Kelly Jackson (w), and Maya Graham (a). The Brownout Murders. Victoria, Australia: Scribe Publications, 2025. 152 pp. US $24.00. ISBN: 978-1-9649-9213-6. https://scribepublications.com.au/books/the-brownout-murders

World War II is a well-documented event within human history, and has served as the basis for a myriad of books, movies, and other media since it started. While many consumers of these media are often far removed from the events of that time, war takes on a simplistic form of a struggle between forces or the civilians who support that effort. One can easily forget the human elements that often become lost in the bigger picture. Crime is one such aspect. It is within this milieu that Luke Jackson and Kelly Jackson set The Brownout Murders.

Set in Melbourne in early 1942, the book centers on Beatrice, a young woman from a home beset with change: a widowed mother, a flawed father, whose vices and death left a hole in the family structure, a flirtatious sister, another sister, who is an avowed Communist, and the uncertainty of the war in early 1942. The setting of Melbourne is also important as it was where American forces first entered Australia to fight in the Pacific theater The fear among the locals is that the Americans will bring an unsavory atmosphere to the town.

Beatrice’s older sister, Lizzie, becomes infatuated with the American servicemen, who look nice in their fitted uniforms, dance, and conduct themselves with a confidence that is very much the opposite of Australian men. However, this attitude often leads to aggressiveness, which exerts itself in drinking, sexual drives, and unwanted advances. Into this “Yank” invasion, a brutal murder occurs near where Beatrice, Lizzie, and their friends met some Americans.

Beatrice also deals with her own struggles as a young woman. She is trying to do the right things within her family and community. She volunteers as a warden to assist with the government-imposed “brownout”--a lessened use of lighting to prevent sightings by Japanese forces during the war, while also working with the Volunteer Defense Corps, which serves, as with the British Home Guard, as an auxiliary military arm. The purpose of the VDC was gathering intelligence, training others for possible guerilla actions, and preparing static defenses in case of invasion.

As another murder occurs, the city becomes more tense, and eventually, speculation is on the newly-arrived Americans. These interlopers, combined with natural rebelliousness of the girls, especially Lizzie and her friend, Maude, lead to dangerous actions, by sneaking out to a U.S. military-sponsored dance on Camp Pell, near the Melbourne Zoo. After a near sexual assault on Maude, combined with a third murder, the U.S. forces are placed in a police line-up. It is after considerable tension that a soldier is identified, arrested, convicted, and hanged for the murders.

While the characters are fictional, the recollections on which they are based were real. It is noted at the end of the book that Patricia Perry, who was an actual brownout warden in 1942, gave an interview describing the tenor of the era. The U.S. serviceman was real: Eddie Leonski was convicted of the murders and was executed in November 1942, for his crimes. Just before his execution, he noted that he killed the women “for their voices,” which enthralled him. The end of the story also gives updates on the realistic scenarios: one sister moves away, one dies of cancer, and Bea and Arthur marry, have four daughters, and go through the same worries and struggles that were there at the beginning.

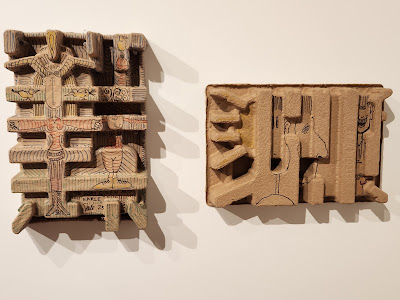

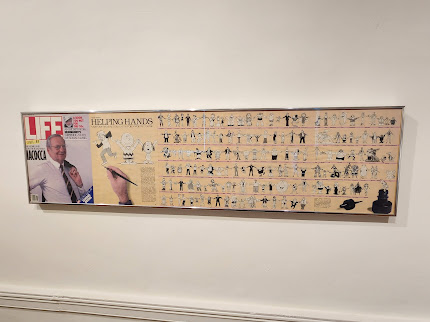

The illustrations are in black and white and take on a tone of a classic suspense film from that era, similar to Fritz Lang’s “M” or Alfred Hitchcock’s “The Lodger.” The illustrations are not graphic in form, but often give clear indication of violence without showing it. This creates a wider appeal for readers of all ages.

The story also touches on a variety of issues that can be easily overlooked within history. There is a dialogue between Authur (who works for the VDC with Beatrice) and her family, in which he is asked why he is not in uniform. He notes that he is considered unfit for service because of his eyesight. This sort of guilt for not serving was a pressure on both the man, and society, throughout the war. It also caused some to commit suicide out of shame. Beatrice’s sisters are also involved in changing mores within society. While Lizzie is more common (the idea of teen rebellion and love), Beatrice’s other sister, June, is a dedicated Communist. In the 1930s and 1940s, Communist involvement was far more active. In 2025, the idea of Communism is not as well understood. It is more often used as an insult without the full context of meaning.

Most importantly, the story arc deals with the issues of sexual assault and crime. An oversimplified view of history allows people to think that crime is much more prevalent now due to the breakdown of societal norms (music, lack of church attendance, sexuality). The story also goes into all too often used “explanations” of assault: the woman is to blame as she gave off indicators. That aspect of the writing was one that was quite effective.

It does take a little while to determine who the characters are, and how they interact, but this is another common aspect of life, as well as media, so it is not a significant issue. In all, it is an interesting, and, for this reviewer, thought-provoking read.

A version of this review will appear in IJOCA 27-1.