a review by Mark McKinney (Miami University, Oxford, Ohio)

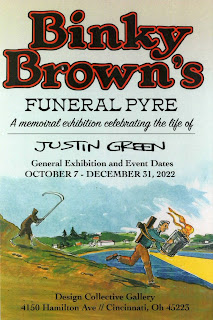

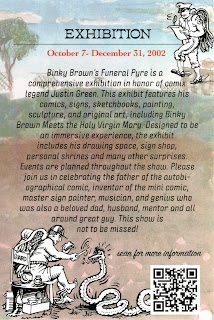

As

the exhibition's title indicates, visiting Justin Green's Funeral Pyre allows

visitors to celebrate and mourn Justin Green. [FIGS 1 + 2] The artist died

in Cincinnati at age 76 of colon cancer on April 23, 2022, according to his

obituaries in several prominent periodicals, including the Chicago Tribune,

The Comics Journal and The New York Times. Justin Green is

best known for his autobiographical work Binky Brown Meets the Holy Virgin

Mary, first published by Last Gasp in 1972, and cited by Art Spiegelman as

having inspired him to write Maus. The exhibition's organizers are Carol

Tyler and Julia Green. Tyler, his wife, is an accomplished cartoonist specializing

in biographical and autobiographical comics, and is therefore uniquely

qualified to represent Justin Green's art and life. So is Julia Green, their

daughter, who is both an artist and owner of the gallery hosting the exhibition.

The exhibition allows the visitor to remember Justin Green in tangible ways,

and to celebrate the art he has left behind, both through the content and

structure of the exhibition, and the stories that Tyler and Julia Green tell

about him and his art. Design Collective Gallery is located in Northside, a neighborhood

northwest of downtown Cincinnati that is known for its openness to the arts and

popular music. For example, just a few doors down from the gallery lies a local

landmark store, Shake It Records, which has a large stock of vinyl disks, a

comics section in the basement, signs painted by Justin Green, and original

artwork by him on the walls, especially full-page comic-strip biographies he

drew for Pulse! magazine, published by Tower Records. The Design

Collective Gallery, with its painted graffiti mural on the outside of its north

wall, and this exhibition, fit seamlessly into the neighborhood. The gallery's

front glass windows are decorated with large black-and-white characters from

comics by Justin Green. [FIG 3] The exhibition opened on October 7, 2022

and runs through December 31 of this year, in Design Collective Gallery (4150

Avenue, Cincinnati, Ohio). It is open from four o'clock in the afternoon to

seven o'clock in the evening on Thursdays, Fridays and Saturdays, or by appointment).

On entering the gallery, visitors are greeted by Tyler or Julia Green, who kindly

give tours of the exhibition. I visited it on Thursday, December 8, 2022, and

was given one.

| | | |

| fig 3 | | |

|

|

fig 4

| fig 5

|

|

The exhibition

is organized into approximately six sections, organically grouped by themes, but

without a strict chronological progression or complete thematic separation

between them. Two large rooms, each of which contains a section of the

exhibition, are separated by a center wall running most of the building's

length, with an open doorway midway that allows passage between the two. The

long left or north room, the first space when one enters the gallery, is titled

"The Underground," after Justin Green's underground comics. [FIG 4]

Julia Green said that the room contained about one sixteenth, at most, of his

underground comics originals, and that the family owns only three pieces of

that work, because her father had sold, traded, or given away almost all of it.

However, thanks to the generosity of current owners of the original art,

several important pieces are part of the exhibition. Moving clockwise around

the room, beginning at the northwest corner of the building, one first sees the

photograph that helped inspire Green's comics collection Sacred and Profane

[FIG 5] (it is also reproduced on the inside front cover of the book).

Taken by Keith Green, the artist's brother (who died in 1995), it shows a sign

in the form of a saw, advertising a store in San Francisco, seemingly laid across

the lower part of a cross that advertises a different, religiously affiliated,

building, as though the tool were sawing iconoclastically through the symbol of

Christ's crucifixion. [FIG 6] The photograph inspired the artist's work

on the comic book, Julia Green told me. Beginning just to the right of the

photo, and stretching across most of the rest of the north wall, a large painting

of a building borrowed from the front cover and page three of Sacred and

Profane artfully frames reproductions of the pages from all five

installments of "We fellow traveleers" [sic] anthologized in the Last

Gasp book, after serialization in Comix Book, a series published by Marvel

and Kitchen Sink Press. [FIG 7] Librarians at the Billy Ireland Cartoon

Library and Museum, at the Ohio State University, generously scanned the

original art, held in their collection, so that high-quality reproductions of

the pages could be displayed here. At the end of the sequence, in the corner,

is original art from the "Rowdy Noody" page on the back cover of Sacred

and Profane, and related originals, including the front cover illustration

of Comix Book no. 5 (cf. the last panel of "We fellow traveleers:

conclusion," part 5).

|

fig 6

|

|

fig 7

|

|

fig 8

|

|

fig 9

|

The right-hand

side of the back wall features a large reproduction of the famous frontispiece

drawing of the naked, chained and suspended narrator of Binky Brown Meets

the Holy Virgin Mary. [FIG 8] Visitors are invited to write down a

title from a bibliography that lists Justin Green's comics and post it in the remaining

blank wall space, so that a wall full of Green's titles appears to emerge from

the pen of his tortured self-portrait as Binky Brown. Against the back half of

the room's south wall are a display case and a long, hung frame containing

sketches, letters and notebooks that document Green's art and his relationship

to it. [FIG 9] Among them is a letter in his beautiful calligraphy that he

wrote in1975 to

|

fig 10

|

Albert L. Morse, the man who had purchased all the original

art from Binky Brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary (1972) for twelve

dollars per page, amounting to just over five hundred dollars for the forty-two

pages. [FIG 10] In his letter, Green bitterly expresses his belief that

he had been exploited by Morse through the sale, and should receive further

compensation from the buyer for his artwork.[1] The

artist suggests that personal problems, including the state of his mental

health, were factors leading to him accept such a small amount of money for his

autobiography. Julia Green explained to me that her father had sold the art to

Morse in order to be able to pay his rent. Together, these artifacts document Justin

Green's artistic creativity, his struggle to bring his comics-related projects

to fruition, and his conflicted relationship to the sign-painting that he began

in San Francisco, before moving to Cincinnati in 1997 and continuing to work in

that profession. The latter was both a source of autonomy, because it enabled

him to pay his bills, and of frustration, insofar as it prevented him from

working fulltime on other creative projects, such as his comics.[2]

|

fig 11

|

|

fig 12

|

|

fig 13

|

On the

front half of the same wall hang several pieces of original art by Green: a

page from the "Projunior" series, a casket sculpture, "Zen

time" (two single-page stories, including the one from the inside back

cover of Sacred and Profane), "The graduate" (one page), two Philip

Morris tobacco advertising parodies, and two versions of a Colonel Sanders

parody page published on the inside back cover of Green's Show + Tell Comics.

[FIG 11] Julia Green intentionally positioned the Colonel Sanders parody

pages near the front of the gallery so that when one stands inside the building

looking out through the front window, the Kentucky Fried Chicken restaurant and

its Colonel Sanders sign located just across the street are visible simultaneously

with Green's parodic drawings of the advertising icon. [FIG 12] Although

the drawings, which show a blood-stained Colonel Sanders slaughtering chickens

with an axe, might seem to suggest otherwise, Julia Green said that her father

was not a vegetarian. She also said that he had smoked cigarettes even though

his parodies refer to the deadly effects that smoking can have. The casket

sculpture appears to symbolize part of Justin Green's

|

fig 14

|

attempt to exorcise the

weight that his Binky Brown series ended up representing for him.[3] [FIG

13] Tyler and Julia Green opened the casket to show me what they had put

inside. The material includes a photograph of the casket at their home in

California, before he shipped it to Ron Turner at Last Gasp comics. At the inside

top of the casket, they placed a pen-and-ink drawing by Green of a naked woman

crouched atop two bound books, reaching out to touch a human skull. [FIG 14]

Tyler told me that the woman could represent her or Julia Green reaching out to

touch the dead artist, and kneeling on top of his art work. Below the drawing

is a two-page letter by Tyler to her husband, dated March 27, 2020, and asking

him for some of the basic documentation helpful to loved ones after a person's

death: preferences for distributing personal possessions, passwords for bank

accounts, and so on. An uncompleted, official-looking form for writing down

one's "Last Will and Testament" is attached just below. Right under

that is perhaps the artist's last drawing, done in red pencil on a yellow legal

pad: a smiling face – of a ghost? – and an arrow facing downward, as though the

answer to Tyler's request for Green's last wishes might be found below.

However, she told me that her husband left no will or final directives. Instead

of a last will and testament, he left a final joke.

|

fig 15

|

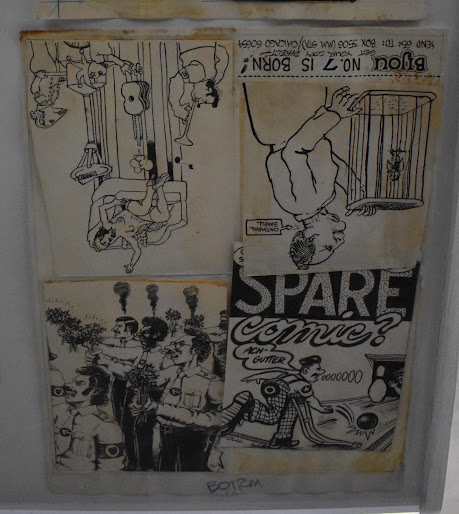

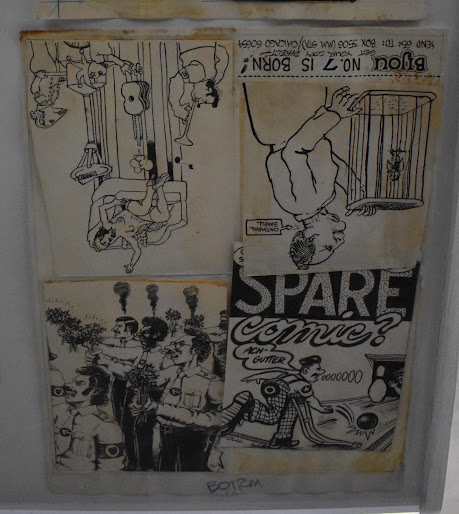

Justin

Green's contribution to the early history of minicomics is featured through

original art in the display case standing in the center of the room. [FIG 15]

In his homage to the late artist, comics historian Patrick Rosenkranz states

that "Justin Green's Spare Comic… initiated the mini-comic genre, along

with 'Jud' Green's Underground Cartooning Course."[4]

Artwork for both of those minicomics is included here. [FIG 16] Julia

Green explained to me that her father would take his minicomics art to a

Kinko's store to reproduce it on photocopy machines. Another minicomic in the

exhibition recounts the birth of Julia Green through the narrative of a stork

character flying to various addresses where her parents had lived, before

finally finding them in the San Francisco General Hospital and passing out on

the floor, after having delivered the baby to her happy parents, shown together

with her in a photo.

|

fig 16

|

|

fig 17

|

The other

large exhibition space is titled "Binky." [FIG 17] A copy of

the first edition of Binky Brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary hangs on the

left wall, followed by a double row of reproductions of its forty-two pages,

lined up in sequence, and of its back cover. [FIG 18] Two installations

and a display stand in the room feature a variety of objects recalling Green's

life and art. They include calligraphic ink pens, a can of used house paint, a

statuette of the Virgin Mary, a Catholic prayer card, and badminton birdies. At

the center of one installation a cloth sew-on patch with the word

"Noyatin," Binky Brown's incantatory word for diminishing the anguish

of his obsessive compulsions, sits atop a large book of Catholic catechism, as

though the patch were there to ward off the Catholic taboos and rituals that

haunted Binky Brown, and his creator. [FIG 19] The back halves of both

left and right walls feature mounted pages with quotations from letters to

Justin Green and from statements about him and his work, made by famous people

ranging from Kim Deitch, Matt Groening, Aline Kominsky-Crumb and Art Spiegelman,

to Federico Fellini, Tom Wolfe and Kurt Vonnegut. Several are excerpted from

the Justin Green memorial organized by John Kelly on the blog of The Comics

Journal.[5]

Tyler and Julia Green also included excerpts from their own published

statements about the artist. This room too contains original art, including

"Binky Brown in Toronto," and, notably, "The 1949 Slinky

Slur," featuring Binky Brown as a boy. The latter story, drawn in 1988,

evokes boyhood rituals of obsessive-compulsive disorder, and critiques bullying

and racist cruelty. The episode might have been taken from the artist's own

life, Julia Green said. |

fig 18

|

|

fig 19

|

|

fig 20

|

Just behind

the long room with "The Underground" section are several small exhibition

spaces. They are set up in a way that recalls living history museums, often

associated with urban or rural working classes, or else living spaces of the

rich that are preserved in fine art museums. These are, in fact, shrines,

carefully and lovingly reconstructed by Tyler and Julia Green, just as is, of

course, the entire exhibition. One of them, titled "Inner Sanctum," reconstitutes

the artist's living space in his final months, but also evokes his entire life.

[FIG 20] It includes Green's plaid shirts arranged on a wall, around one

of several mandelas that he painted close to the end of his life to try to cope

with his illness and his mortality. [FIG 21] On the floor lie his

paint-stained clogs. His guitar is propped up against an armchair. [FIG 22]

Tyler told me that she had placed the urn with Green's ashes on the chair for a

memorial ceremony. During the event, family members brought and laid on it,

next to the urn, personal objects with special meaning for the artist and his

life, such as a drawing he made as boy that symbolized his lifelong desire to

follow his own path, which was opposite from that of others. A printed page

with the ceremony's order of events rests on a filing cabinet. Above the

armchair hangs a self-portrait that Green painted while in high school. His

books and personal photos sit on a bookcase and shelves. On a wooden stand lies

a hot plate on which he heated up substances contained in labeled bottles and

cans, concoctions with which he tried to cure himself of the cancer that

finally killed him, as Tyler explained to me.[6] [FIG

23]

|

fig 21

|

|

fig 22

|

|

fig 23

|

|

fig 24

|

Outside the

"Inner Sanctum," in a hallway leading toward the gallery's back room,

is a display case with samples of Green's calligraphic work, made for a friend.

In other display cases and attached to the wall are dozens of pieces of

original artwork by Green, for a myriad of projects, ranging from Binky Brown

stories to his Pulse! magazine work, and projects for cartoons and

comics. [FIGS 24, 25] One, a cover illustration for a projected but

never published collection of drawings, is titled "Notes before closing

time, Justin Green, Cincinnati, 2009." On it, the grim reaper's reflection

appears in a mirror, startling the artist, who is sitting at the counter of a

bar or a diner. [FIG 26] Tyler told me that he was always thinking about

death. Green's sign-painting work is also featured prominently in this area.

Artifacts include a sign he made to advertise his sign-painting business, and sketches

for signs he made for others. The last sign he painted, for the bathroom in

Julia Green's gallery, is at the end of the hall, around the corner.

|

fig 25

|

|

fig 26

|

|

fig 27

|

At the

very back of the gallery, in a large workshop or storage area, lies another

installation. [FIGS 27, 28] It reconstructs a scene that Justin Green

painted: a pastiche of The Art of Painting (or The Allegory of

Painting; circa 1866–8). The latter is a self-reflexive representation of

the art of painting – a self-portrait of the artist in the process of painting

a woman's portrait – by Johannes Vermeer van Delft.[7]

Green made his version, depicting "a small sign shop somewhere between the

Vietnam Era… and 1986," to illustrate the front cover of the October 2001

issue of Signs of the Times, a national sign-painter's monthly magazine based

in Cincinnati, to which he contributed a comic strip for years. [FIG 29]

Through his own self-reflexive image, Green asserts that sign painting and

cartooning are both arts, just as was the work of the Dutch old master. Tyler

and Julia Green both described Justin Green's masterful sign painting skills for

me. His former partner from his sign painting business in California helped create

the installation for the gallery, including by printing the large backdrop

behind it. A poster version of Green's page is available for sale from the

gallery. Tyler told me that her husband had asked her to have copies printed as

presents for the caregivers at the hospice where he spent his final days. A

copy of the poster is attached to an easel set in front of the built

installation, so that one may view together, in a meta-representational mise-en-abîme,

both the poster and the (rest of the) installation, which reproduces the scene

that Green depicted in his illustration.

|

fig 28

|

|

fig 29

|

|

fig 30

|

|

fig 31

|

The remaining

installation is titled "The Studio." Situated across the hallway from

"Inner Sanctum," it is itself another self-reflexive artistic work,

and also again contains one. The installation recreates Justin Green's

cartooning workspace, which Tyler and Julia Green took from home and reassembled

in the gallery. [FIG 30] It is a three-dimensional mise-en-abîme that

incorporates a two-dimensional one: original art drawn by Justin Green and referring,

like "Notes before closing time," to his impending death. On his own

wooden easel, below his desk magnifying glass, its light still on, sits a

half-finished illustration, as though he had just stepped away from his work. [FIG

31] As Julia Green pointed out to me, the image is exceptional in terms of

her father's usual creative process, because instead of being wholly at one

stage – say, the pencil rough, or the page then being inked, or colored – it

combines various stages. The illustration's title and image suggest that this

was entirely intentional, and that the artist meant it to be his final artistic

statement. The title is "The last will and testament of Binky Brown, by

Justin Green." Just as does the installation in which it is set, the image

represents Green's drawing studio, with his easel and chair, pens and inks,

paintbrushes and paints. The lower part of the image, still in the pencil rough

stage, depicts the artist seated at his desk, with a mostly empty thought

balloon above his head. He is turning around, because he is being called away right

in the middle of his work. "Let's go, pops!" says a thin, skeletal

figure with a scarf around its neck, standing behind the artist. This is

clearly death summoning Justin Green before he has completed his final project,

perhaps an anthology of his comics, something he had imagined doing but was

never able to complete. We might also view the illustration as a reflection of

the artist's relation to the entire exhibition itself, which – Tyler and Julia

Green have said – he had hoped to see through to completion before his death.

|

fig 32

|

According

to Julia Green, it was her father who titled the exhibition "Binky Brown's

Funeral Pyre."[8]

This meta-artistic statement must be yet another self-aware irony of Justin

Green, to which those he left behind have given form. If a funeral pyre

involves heaping personal effects in a pile and lighting them to feed a fire

that cremates the deceased, here, instead of being piled up and burned, those

effects are exhumed and laid out carefully in sequences. They are relics of the

dead artist, carefully and lovingly arranged so that the living may both mourn

and celebrate him. In fact, Tyler told me that she is currently making a book

about mourning. While I visited the exhibition, listening first to Julia Green

and then to Tyler tell me about the artist's life and work, family friends came

in, viewed the exhibition, and chatted with them. Recordings of Justin Green playing

the blues on his guitar provided background music in one of the rooms. To visit

the exhibition, and to listen to his wife and daughter speak about him, is be

able to participate, empathetically, in a kind of ritual, both sacred and secular,

in something like a wake for the dead artist, someone who made tremendous artistic

accomplishments, despite suffering enormous pain throughout his life, because

of his anxiety and obsessive-compulsive disorder. The exhibition teaches us

much about Justin Green's life and art, but we will soon be able to learn even

more. Carol Tyler and Julia Green are planning publications of Justin Green's Binky

Brown series and other comics, sketches and notes, correspondence, and no doubt

much more. [FIG 32] A book biography of the artist by John Kelly is in

the works, as is Married to Comics, a documentary film by John Kinhart about

Carol Tyler and Justin Green, with a release planned in the near future.

The

author took all the photographs that illustrate this review. The art and

installations in the illustrations are all © the Estate of Justin Green. Any

republication of the photographs requires prior authorization from the author

and from the executors of the Estate of Justin Green.