by Warren Bernard

It was clear to US Army leaders

after the blitzkrieg of 1939-1940, where German tanks overran first Poland and then

most of Western Europe in a matter of weeks, that World War II would be

conducted with mechanized warfare to a far greater degree than previous wars.

The numbers of vehicles (tanks, half-tracks, cargo trucks, troop transports,

etc.) would dwarf those built during the World War I. Mobility of troops and

supplies in the war would be paramount, and to that end by 1945 the United

States alone produced over 2.3 million trucks, 640,000 jeeps and 88,000 tanks,

plus tens of thousands of other vehicles.[i]

The Army also controlled the air

force (known then as the Army Air Force), which would not become a separate

branch of the armed services until 1947. Planes, of which the United States

produced 297,000 by the war’s end[ii],

added more stress to maintenance duties around the world in that their engines,

landing gear, bombs, bomb bays, machine guns and other parts / systems would

need regular servicing and a high degree of mechanical skill.

Working against the Army’s needs at

this time was the education level of the typical draftee. In 1940 only 25% of

males over the age of 25 had a high school degree, with high school graduation

numbers just over 50%.[iii]

There was an overall literacy issue in the armed forces because of these

societal deficiencies. New methods needed to be implemented to train not only front-line

soldiers how to care for their equipment, but also the mechanics and other

support troops spread around the world to service planes and mechanized units.

Into this

educational void was thrust William Erwin Eisner (1917-2005). One of the

pioneers of comics, his creation The Spirit, that ran as a comic book

newspaper supplement from 1940-1952, is considered one of the great hero

characters of The Golden Age of Comics (1938- ca.1956). Eisner's use of splash

pages, innovative panel layouts and adult-aimed stories influenced many comic

books artists in subsequent generations. He is also considered either a father

or godfather to the form of the graphic novel, as both an advocate and creator

in that genre, although historically he did not invent the graphic novel

concept.

Eisner

received his draft notice in December 1941, soon after the United States

declared war after the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor. At that time, he was

running a comics production shop that published The Spirit, along with

providing Quality Comics and other publishers with complete comic book stories.[iv]

He was able to defer his enlistment to take care of setting up his business to

run in his absence until he was inducted May 1942.[v]

Eisner’s basic training was at Fort Dix, New Jersey, after which he was

posted to the Aberdeen Proving Grounds in Maryland. It was there that Eisner

came up with the idea to use comics to help train army troops, creating the

character of Joe Dope to exemplify what one should not do to their equipment.

This idea was embraced by his commanding officer, who then transferred him to

the Holabird Ordnance Center in Baltimore.

On

September 7, 1942, the Adjutant General of the Army, James Ulio sent out an

order that effective that month, Joe Dope posters were being distributed to all

“posts, camps and stations” around the world. The backs of some of the posters

have the original order, along with instructions on where to hang

the posters. Below the hanging instructions, Eisner drew a cartoon

emphasizing the proper placement of the poster.

Per Ulio’s orders, the first three

posters were issued every two weeks starting in September 1942, and that

posters were to be distributed weekly after that. It is clear from the research

that this rate of poster publication was never fulfilled, as to date only 52 of

these posters have been identified after research from the National Archives

(NARA), Library of Congress (LoC), private collections, and auction sites. The

posters covered a wide range of equipment, including machine guns, trucks,

tanks, mortars, and planes, among others. They also gently prodded supply

depots to fill out the correct forms and not over order or hoard spare parts.

Fifteen of the posters were specifically made for the Army Air Force, with

seven other posters made for the Pacific Theater. Though it is known that there

were 20,000 of the first posters printed, additional research is needed to see

if any documentation exists for the actual print run totals. It is not known at

this point whether Eisner chose the poster topics or they were assigned to him.

While at Holabird, Eisner joined the

staff of Army Motors magazine that

was published there for distribution to all army bases around the world for

mechanics, soldiers, and support staff. Army

Motors began its publication history in May 1940 as an 8 ½” x 11”

text-only, black and white mimeographed publication. By the time Eisner came on

board in mid-1942, it was still the same size, but now it was staple-bound with

a spot-colored cover. The interior used photographs and line drawings to

communicate different aspects of maintaining equipment. A wide range of topics

were covered in Army Motors, from

maintenance issues with tanks, to how to prepare trucks for use in cold weather

and how to lubricate a jeep, among thousands of topics covered during its

5-year run.

The November 1942 issue of Army Motors introduced Eisner’s Joe Dope

to the Army:

Joe Dope is the doggondest fool in the Army!!!!

A new character with a desperate destiny designed to call

attention to habitual failures in maintenance of all Army equipment. Humor

without bitterness but stinging with its truthfulness. Joe Dope posters will

drive home a point quickly…. And with little or no pain!

The posters

of Joe Dope were successful enough to spawn a two-page comic strip by Eisner

that began in the April 1944 issue of

Army Motors, continuing until the magazine ceased publication in September

1945. Eisner would resurrect Joe Dope during the Korean War in 1951, when he

left his creation, The Spirit, behind

to become a government contractor. He used Joe Dope as the centerpiece in his

new undertaking, PS: The Preventive

Maintenance Monthly, for the U.S. Army.[vi]

Covering the same topics of equipment maintenance, PS magazine was an updated and expanded version of Army Motors, down to the use of the

digest format Eisner had introduced for Army

Motors in the summer of 1944. Eisner remained with PS for twenty years until 1971, at which point he returned to the

comics field as a teacher and the creator of new works that would renew his

stature as one of the greats in the world of comics.

This attempt to create a catalogue

raisonné listing all of Eisner’s Army posters was conducted over a period of

years, and the following information was captured: Artificial title using 1st line

of rhyme; year; Eisner's rank; Eisner's organization (as signed on poster); audience;

LoC / NARA holdings; Government Printing Office # / other ID; LoC received date;

notes. The information is presented in two ways - as a caption to an image of the poster, and as a table at the end of the article.

A rock to Joe Dope is a trifle 1942 Pvt. Aberdeen Pvg. Gds. Both (LoC and NARA) 478618

At maneuvers Joe Dope took a tank 1942 Pvt. Both 481419

In helping assemble a mortar 1942 Pvt. Both 481418

Joe Dope camouflaged his Garand 1942 Pvt. Aberdeen Pvg. Gds. Europe Both 478615

Joe Dope has a vague premonition 1942 Cpl. Both 498371

Joe Dope has a way that's unique 1942 Pvt. Both 481417 2/15/1943

Joe dope has the habit, we fear, 1942 W/O LoC None 1/13/1943

Joe Dope is a guy you can't teach 1942 Pvt. Ord. Tng. Division Both 481420 2/26/1943

No obstacle that he may meet 1942 Pvt. Aberdeen Pvg. Gds. Both 478619

The book says to run a car right 1942 Cpl. Europe Both 498372 2/18/1943

The Sheik thinks it terribly strange 1942 Cpl. Ordnance Dept North Africa Both 498733 2/2/1943

The tank crew is sore as a boil 1942 Pvt. Both 478620

When the Stukas begin to attack 1942 W/O Ordnance Both 553727

A maxim Joe Dope just pooh poohs 1943 W/O Both 10/11/1943

Aloft in the thick of the fight 1943 W/O AAF Both 562295 1/19/1944

At fixing things I'm a bear! 1943 W/O Ordnance Both None 9/1/1943

Behold Joe Dope hitting his stride 1943 W/O AAF Both 553727

I'm tired of taking the rap 1943 W/O Ordnance AAF Both 10/11/1943

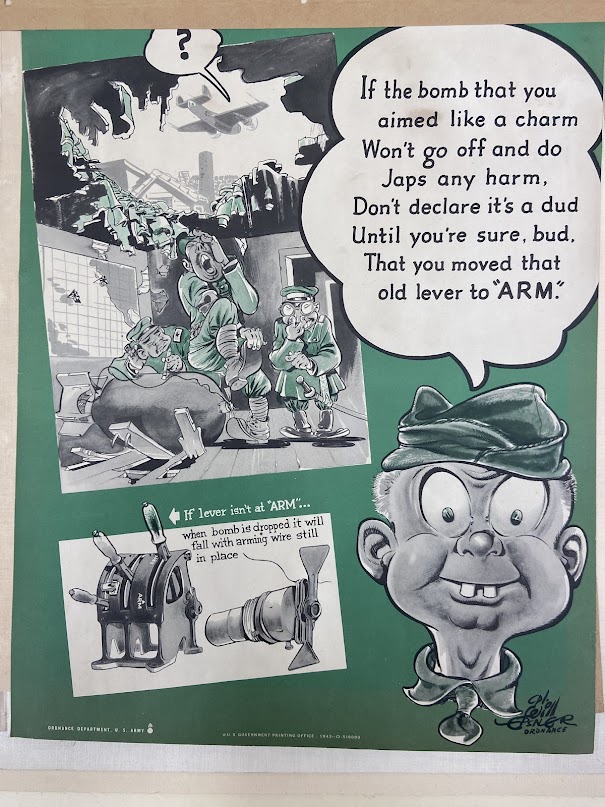

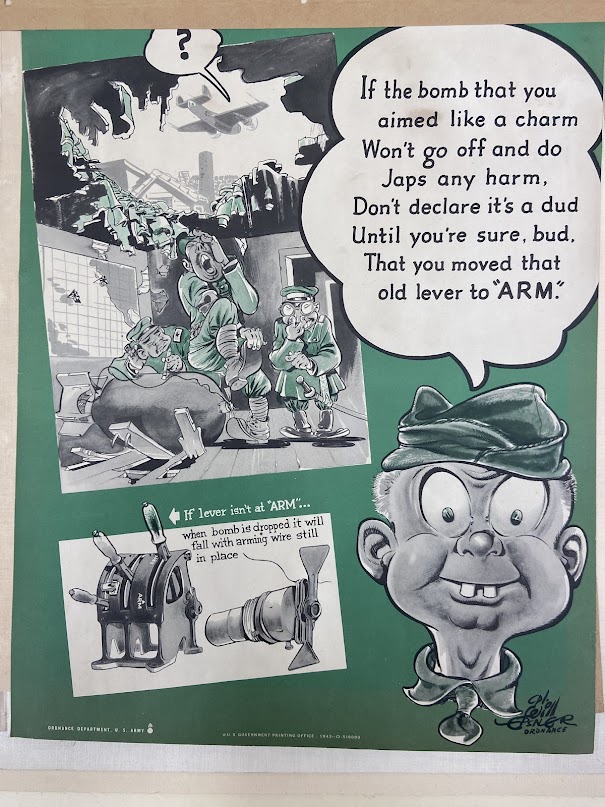

If the bomb that you aimed like a charm 1943 Cpl. Ordnance AAF, Pacific LoC 518000

Joe Dope is a regular ace 1943 W/O Ordnance Both None 10/11/1943

Joe Dope says "Should I get KP... 1943 W/O Ordnance AAF LoC PMU Holabird A-6 8/26/1943

Joe Dope says, "Why bother to clean... 1943 CWO Ordnance NARA 565905

Joe Dope should get thrown in the can 1943 W/O Ordnance AAF, Pacific Both 518000

Joe Dope thinks it funny to play 1943 W/O Ordnance AAF, Pacific BotH 518000 4/24/1943

Misled by publicity stuff 1943 W/O Ordnance NARA 553727

No friends, this is not the location 1943 None Ordnance LoC 7/13/1943

The poet says "What's in a name?" 1943 Warrant Officer NARA 562294 Verso has letter from Adjutant General and illiustration by Eisner as to how to hang them

These pilots will "gently" explain 1943 W/O AAF Both 518000

To prove he's game as the flyers 1943 Cpl. Ordnance Both 512339

While draining the oil one day 1943 Unsigned Both 512339 5/8/1943

"Who's (sic) 'borrowed' the damn arming wire 1943 W/O Ordnance AAF LoC 552727

With an air of complete unconcern 1943 CWO Ordnance Both 565904

Don't hoard spare parts 1944 CWO Both 577520 (non-limerick)

Don't wash vehicles in... 1944 CWO Pacific Both 595006 8/25/1944 (non-limerick)

Joe Dope isn't bug-house or crazy 1944 [Ordnance] Both 62235 Maybe not Eisner? No signature, does not look like his art

Joe Dope takes good care that his hide 1944 Unsigned AAF, Pacific Both 569901

Joe Dope, friends, has done it again 1944 CWO Pacific Both 569902

Shock absorbers left to get dry 1944 Unsigned Ordnance Dept. Both 622350 2/21/1945

The Tower of Pisa would shy 1944 CWO Ordnance NARA 606762 War Department Safety Council

To Joe Dope ring-round-rosie is fun 1944 Unsigned Ordnance Both 62235 1/24/1945

By fireball pilots like Joe 1945 CWO Ordnance AAF, Pacific LoC 684706 8/6/1945

No more good than the bag at the left 1945 Unsigned LoC 631775 3/30/1945

Oh, one cannot really decree 1945 Both 631775 3/30/1945

The guns on this new '-38 1945 CWO AAF NARA 631774

This rather acute situation 1945 Cpl Aberdeen Pvg. Gds. LoC 631775 3/30/1945

The reason for Joe Dope's new entangle 1945 CWO For Air Ordnance AAF, Pacific NARA 631774

To the pilot that's giving him sass 1945 For Air Ordnance AAF NARA 631774

Headspace to Joe Dope was a riddle, None W/O Europe Both PMU Holabird

Joe Dope cleaned his rifle, oh yes - None W/O Ordnance Both P.M.V - H.O.D (Holabird Ordnance Depot)

Joe Dope takes a constant vacation None W/O Ordnance Pacific Both None Co-signed with H.C. Minor. Possibly trimmed.

On high over enemy soil None Warrant Off. AAF NARA

The caissons go rolling along None Unsigned Preventive Maintenance Department NARA

The "T-Slot" you carelessly clean None NARA 514706 from https://picryl.com/media/the-t-slot-you-carelessly-clean-will-pit-and-soon-form-a-space-seam-ruptured-62ad2f

The "T-Slot" you carelessly clean

Will pit and soon form a space-seam.

Ruptured cartridge at best

Will result, and the rest

Joe Dope best describes what we mean.

To view the spreadsheet below, right click on it, and select "This Frame" and then "Open Frame in New Tab."

Warren Bernard is an independent

scholar and the director of the Small Press Expo (SPX).

A version of this will be published in IJOCA 27-1. Updated 6/17/2025 at 11 PM with the poster The T-Slot you carelessly clean, and modifying the title to Catalogue Raisonne, as Wikipedia says it's never Anglicized.

[iv]

In the early days of superhero

comics, a comics “shop” was a separately-run company composed of comics artists

and writers that would produce stories and create new superheroes for larger

publishers. Some shops distributed their own works, as Eisner did with The Spirit, but the majority of their

work was used and distributed by the large publishers. This outsourcing reduced

the amount of staff, coordination and overhead required to produce a publisher’s

stable of comic books.

[v]

Michael Schumacher, Will Eisner - A Dreamer’s Life In Comics.

New York: Bloomsbury, 2010. p. 82.