|

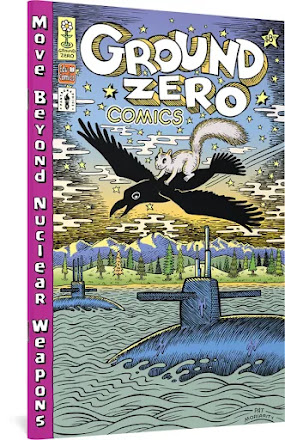

| art by Pat Moriarty |

Leonard Rifas, et.al. Ground Zero Comics: Move Beyond Nuclear Weapons. Seattle: Fantagraphics, 2024. https://www.fantagraphics.com/products/ground-zero-comics-move-beyond-nuclear-weapons

Leonard

Rifas is comics’ most enduring anti-nuclear activist, a tireless advocate for nuclear

disarmament and non-proliferation. For over fifty years Rifas has been producing

educational comics on the dangers of atomic weapons and nuclear power, as well

as an array of other causes (such as food production, energy policy,

motherhood, and corporate crime). Ground Zero Comics sees Rifas return

to anti-nuclear comic books, with his new one serving as both a history of the

anti-nuclear movement and a call to action. Arguing that we are in a new

nuclear arms race, Rifas calls on ordinary people to challenge US policy through

protest and activism. As Rifas puts it, “If we’re going to make it through the crises

… a lot of things will have to change. If we have no voice,

we’re not going to survive.” (32) Ground Zero Comics, a continuation of Rifas’

commitment to independently-produced educational comics, combines traditional

cartoons and sequential comic strips with maps, graphs, charts, and scientific

diagrams. Rifas combines his alternative comix sensibilities with the

publishing power of Fantagraphics to create a slick and professional product.

While

Rifas is the driving force behind Ground Zero Comics, he divides

artistic duties with three other interior artists: David Lasky, Max Clotfelter,

and Kelly Froh. Each is responsible for one of the comic’s four sections, with colors

overall by Lasky. The first section introduces the central narrative, as a crow

and a squirrel teach an unnamed protagonist about nuclear weapons. These pages feature

Lasky’s illustrations over street maps and satellite imagery, covering the

history of nuclear weapons in Washington state. Rifas, who resides in Seattle,

concentrates much of his attention on the Pacific Northwest and its nuclear

industry and anti-nuclear movement. Because of this, Ground Zero Comics

can, at times, feel geographically isolated. The Space Needle, the Columbia

Center, and the University of Washington function to illustrate scale, but

provide a narrow point of reference for non-Washingtonians (or, indeed,

non-Americans).

In

the second part, Clotfelter covers the science behind, and destructive consequences

of, nuclear weapons. His loose art style is the most reminiscent of the 1970s

comix tradition that Rifas emerged from, and his illustrations of burned,

irradiated, and mangled bomb-victims carries a commensurate sense of horror.

One illustration on page 9, blending his style with that of Barefoot Gen’s

Keiji Nakazawa, is particularly effective. Here Lasky leans into vibrant greens

and pinks for a psychedelic style that accentuates the uneasiness of

Clotfelter’s art.

Rifas

provides art for the third section of Ground Zero Comics. This, along

with the final section illustrated by Froh, feature the most traditional form

of illustrated comic strip, with fewer infographics and maps. In Froh’s section

the protagonist’s grandfather tells her about his personal history of

anti-nuclear activism. This comes across as the most personal to Rifas. I was

left wondering how much of the grandfather’s account was autobiographical, with

a call to action motivated by the knowledge that “if dying old anti-bomb

activists are not replaced by young activists, the anti-bomb movement dies with

them.” (30) Ground Zero Comics argues that demonstration and protest

have been successful in the past and can be again: “Much of the credit for

stopping the drift towards nuclear war belongs to the millions of

ordinary people around the world who joined or supported movements to demand peace

and nuclear disarmament.” (29)

The

choice to utilize multiple artists can lead to a jarring and incongruous

mixture of text and art. It’s most successful in the sections illustrated by

Clotfelter and Rifas, where the fusion of cartoons, satellite imagery and

google maps, enhance the text. Unfortunately, the text of the final section fits

uncomfortably alongside Frohs’ art, which is missing the same data-led imagery

of earlier sections. The visualizations of scientific and geographic data in

earlier sections enhance the illustrations, and this final section suffers for their

absence. Lasky’s coloring lacks the same depth here, as talking heads opine

against flat colored background panels.

It

should also be noted that not all of the graphs and charts included are

successful. A graph showing the potential impact of nuclear war shows

population growth since the year zero (17). While it adequately shows that a nuclear

war would see a massive drop in global population, there is no way for this

graph to demonstrate that while hundreds of millions might die in the war, the

majority of the population loss would come in the following years (seemingly

recognizing this the comic adds in the fact that the “number of people who

would starve to death after two years: over five billion”). A shorter time span,

showing only the world population today and deaths over the years after an

atomic war would help to demonstrate this.

Ground

Zero Comics is clearly designed to be used in a

classroom setting, and some of these issues could be mitigated by discussion.

This is, ultimately, where Ground Zero Comics shines. Throughout, Rifas

provides activities for readers, from drawing “a picture, image, cartoon,

illustration, or graphic that represents “nuclear weapons”” (7) to

opportunities for readers to think about their own stance on whether the US

should dismantle her atomic arsenal, the scale of American military spending,

and the utility of protest against nuclear policy (21). Each section could be isolated

and given to high school or university students (although the text seemingly

assumes an older audience, as one activity includes calculating how much of the

readers taxes go to nuclear weapons).

Perhaps

the most telling evaluation of Ground Zero Comics then is not about the

comic itself, but how it can be used. If the audience is unclear, and the

materials relevance outside Washington is more limited, it does provide an

obvious and replicable model for educators to adapt. Rifas’ infographics and

activities provide excellent starting points for discussion or teaching, even

if student don’t end up reading the entire comic.

To

supplement this, Rifas and the Ground Zero Center for Nonviolent Action also

provide a substantial online resource pack, containing “a hundred pages of

solid documentation, lesson plans, further thoughts, and fun facts,” available

at https://www.gzcenter.org/comic_book_sources.

This is ultimately best considered (in conjunction with the online resources)

as an academic aid for anyone looking to teach on the history and morality of

the bomb. In this respect, Ground Zero Comics is an invaluable

introduction that comprehensively and thoughtfully discusses the arguments around

nuclear weapons.