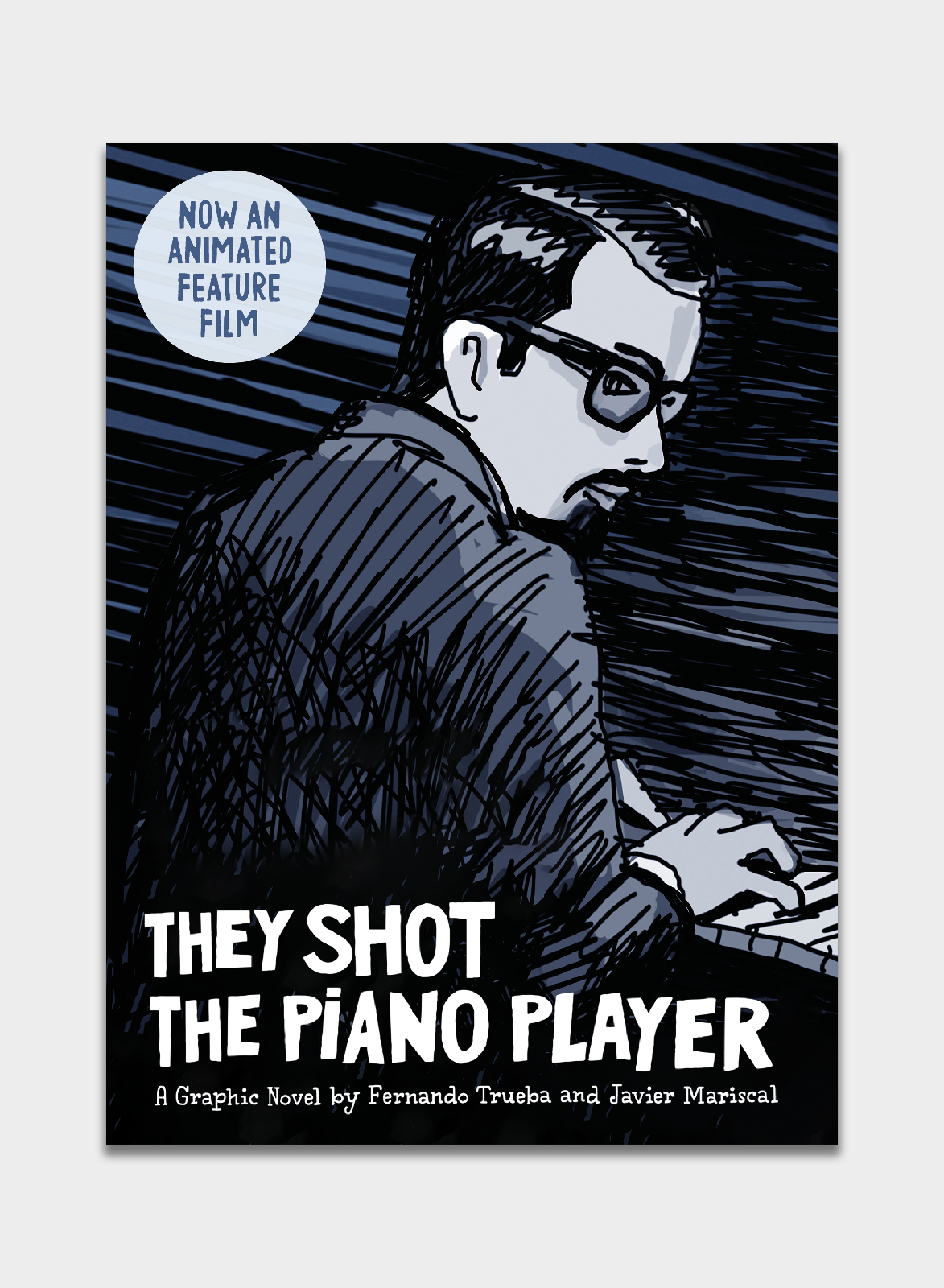

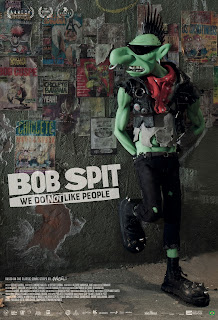

Bob Spit – We Do Not Like People, Cesar

Cabral. Coala Filmes, 2021.

Bob Spit – We Do Not Like People, Cesar

Cabral. Coala Filmes, 2021.

Reviewed by Pedro Moura

Bob Spit is an hour-and-half

stop-motion animation/feature documentary film directed by Cesar Cabral about

Brazilian cartoonist extraordinaire Angeli. The film was awarded Best Feature

at the Contrechamp section in the international animation festival of Annecy in

2021, a section which is “dedicated to,” in the words of Variety's Jamie

Lang, “emerging talent from around the world and

films that lie outside the mainstream.”

As the title reveals, the focus of attention is

Bob Spit (originally “Bob Cuspe”), one of Angeli's most known characters from

the 1980s. But it also threads the needle through the artist's oeuvre, his

creative block, his aging, and a fair degree of nostalgia. This is a

non-fiction project mixed with fiction, in which we'll slide through various

degrees of remove from a purportedly “real” - stop-motion animation,

documentary angles, the diegetic world of the character, historical

contextualizations, fantasy, and so on.

Without wanting to rehash the discussion about

the feasibility and pertinence of talking about “animated documentaries,”

something that has been discussed by people far more informed than me, I

believe that Bob Spit will nevertheless become a very good example of

such an expanding field. Foremost, for being an exploration of interpretative

frameworks larger and more profound that a supposedly “objective” or

“journalistic” approach. We literally delve into Angeli's psyche, but in

an oblique manner, so instead of having clear-cut decisive conclusions, we are

rather invited to keep on thinking about the issues for ourselves.

The film follows two major storylines. On the

one hand, we have an interview set in Angeli's apartment, where he clearly

answers an interlocutor sitting off camera, discussing his work, career and

life, showing archival material, and sometimes accessing third parties that

talk about him. Angeli finds himself in a bind, and refuses to be stuck to

older glories. So he resorts to recycling a strategy and decides to kill off

Bob Spit, as he did before with other characters.

On the other hand, we follow what seems to be a

fictive roadtrip adventure. The titular character, Bob Spit, embarks on a

journey, crossing a desert-like, post-apocalyptic landscape, in his quest to

meet his creator, Angeli. After learning of the cartoonist's plan to kill him –

through the “prophecies” of tattered pages of the comics he stars in – Bob vows

to take vengeance on his own creator.

We must always bear in mind that when we’re

speaking of this whole interview setting, we are referring to a construction.

After all, everything is depicted through three-dimensional puppets and

backgrounds. The artificiality of the interview is made “natural” by making

visible the presence of the filming crew, not only through dialogue but also

through metatextual techniques such as video framing, timestamps, and other

materiality traces. But if animated documentaries allow us to go well beyond

indexicality, some of the less conventional techniques followed by Cabral bring

about other issues, that keep us off balance and therefore alert at all times.

For instance, there are momentary “glitches”

that allow us to see the actual photographic footage of the interviews Cabral

and his crew did with Angeli, which can be seen as the supposed scaffolding of

the final animated plane. So the film never leaves us in a continuously

comfortable state of watching what unfolds. We are permanently jarred back and

forth in these dimensions. According to Annabelle Honess Roe, “the use of

animation as a representational strategy broadens the potential of documentary

by expanding the range of what can be shown and told” (Animated Documentary).

And what is shown and told in Bob Spit goes well beyond the Brazilian

cartoonist's take on his own work.

Somewhat like the Quay Brother's Street of

Crocodiles, it's as if we have access here to multiple levels of reality

and existence – Angeli's “normal life” and Bob Spit's imaginary adventure

storyworld –, but we do not have a precise map of how one level relates

ontologically to the other. It would be easy to say that the latter is an

extension of Angeli's “imagination” or “stories,” but it gets more complicated

than that, in a crooked Lynchian logic sort of way. Nevertheless, there is a

certain coherence and fluidity to this patchwork, as the director dovetails the

artist's life, thoughts and art into a continuous unfolding thread. Mostly,

this stems from the overall framing of Angeli's voice taking precedence over the

whole narrative. At one point, someone asks Angeli if they can ask him a

question. Angeli simply answers, “No.” Not because there are no questions to be

asked or no answers to be given, but because we are always already within the

discourse that makes up the whole text.

Notwithstanding, the projects allows for a

number of shifting points of view. Apart from Angeli's speech, we go into the

fictive underworld of Bob Spit, even if his adventure is mostly framed by the

Kowalski twins. But, as mentioned above, we also have access to Angeli's wife

Carol, fellow cartoonist Laerte (yet another giant from the 1980s, still

extremely active today and admired by Angeli) and the ex-editor/taxi driver,

which has a few words of choice about the author. Later on, other characters

appear, bringing other types of “glitches” into the mix.

Arnaldo Angeli Filho was born in São Paulo in

1956, and belongs to a generation of self-taught artists who were heavily

influenced by the preceding golden age of Brazilian illustrators, comics

artists and cartoonists, upholding thus a genuine national tradition, even if

mixing it with the most diverse sources of foreign material. In Angeli's case,

the influence of Robert Crumb is unmistakable, specifically his ability to come

up incessantly fully formed characters, many of which would become recurrent.

From the hippie duo Wood & Stock to the sexual deviant Rê Bordosa and, of

course, the anti-social yet shrewd commentator Bob Cuspe.

Most, if not all of these characters were born

in the daily strips he created in the early 1980s in the pages of the Folha

de S. Paulo, in which he had been working as a very politicized and

combative editorial cartoonist since 1973. Around that same era, his interest

for comics proper lead him to several editorial projects, thanks to a

collection put out by the publishing house Circo, called Chiclete com Banana

(“Gum with Banana;” really, I'm not kidding, it's not “of”). Its success was so

great that the publishers decided to give Angeli a regular magazine. This also

heralded an outstanding number of influential titles presenting a powerhouse

new generation of cartoonists, including Laerte and Glauco, with whom Angeli

would form an informal trio for years to come.

Chiclete com Banana would

feature then a plethora of characters, including the “pervert” variant of the

two-kid team trope Skrotinhos to con man/spiritual leader Rhalah Rikhota, both

of whom appear in this very same film. But many, many others would be penned by

Angeli, all of them hilarious stock characters very much related to the

cultural specificities of the city of São Paulo (arguably the cultural capital

of Brazil, or at least so “Paulistanos” like to believe).

This is not the first time Angeli is involved

with filmmaking. In 2006 Otto Guerra adapted another character-driven strip into

Wood & Stock: Sex, Oregano and Rock'n Roll. Cesar Cabral

directed first a short based on Rê Bordosa in 2008, and in 2017 launched a

television series called Angeli the Killer, in which he adapted many of

the cartoonist's stories, brought his characters to life and conducted (and

animated in stop-motion) interviews. To a certain extent, Bob Spit, the

movie, is an extension of that project. But it is also a simplification, as it

attempts to create a more or less linear and organized structuring of its themes,

instead of the more loose, hectic and even frantic pace of the tv series.

Bob Spit brings a visual dynamic that

was not extant in the original material: color, three-dimensionality and a

certain lightness to it all. We should bear in mind that Angeli's original work

was made out of heavy, “scratchy”, “dirty” hatchwork, very typical of a certain

underground aesthetics. Coloring, and subdued, murky one at that, would come

later. But Cabral's own capability for character design and construction, their

dynamic movements, the framing and camera work makes up for a technically solid

piece of work. Cabral’s use of an incredible variety of sounds sources,

including “classic” Brazilian punk rock anthems of the 80s, creates nonetheless

a seamless surface that eases the many transitions between planes and subjects.

To watch a stop-motion character drawing on paper is an amazing experience,

even if for the briefest of moments.

To be precise, while the main two storylines are

depicted through stop animation techniques, there are other interpolated

techniques, used as brief transition bumpers (but which sometimes are also used

to convey further contextual information). In some of these, the animations

made out of the strip's art – basically quickly superimposing several of the

strips' panels, but judiciously choosing similar positions of the character— is

superb. And these scenes are particularly good precisely because they do not

aim to disguise their origins or bring up the idea that “animated cartoons” are

better than the original drawn cartoons, but because they leave visually

present the variegated materiality of the original newsprint, including within

their transition effects.

While Angeli's more recent work is slightly more

introspective, sometimes with the cartoonist drawing himself, and engaging,

quite often with zen-like adages, his 1980s and 1990s work, from which this

movie stems, was quite virulent, frank and adversarial. In a word, punk. But

what is at stake in Bob Spit is not simply an adaptation of those

stories. Angeli appears in his present age, preferring to stay home, listening

to records, working alone and uninterrupted. And Bob Spit himself is not his

old self, living in the busy streets of São Paulo. He looks slightly tired,

living off the flesh of maimed mutant Elton Johns, unable to spit (his

trademark move, and hence his name). The possibility of killing his creator is

the only little spark of joy that seems achievable, and even that does not

change his demeanor. To put it simply, neither creator nor created character

are the personalities that they once were, and that most people remember. There

may be a hint of nostalgia in making this documentary, but both Angeli and Bob

Spit himself suffer no fools gladly and are willing to disabuse people of their

expectations.

Another potentiality of the animated documentary

underlined by Roe is its capacity to what she calls “pointing inwards,” i.e.,

the possibility of employing non-mimetic strategies that go beyond issues of verisimilitude

and evocative planes that open up to more complex, less directly accessible

emotional or inner mental states of the portraitee. In this case, many of the

silences, hesitations and half-explored emotions by Angeli gain a body of their

own in the imagetic translations. While

the film is not dealing with repressed memories or clear-cut traumas, as is the

case of the world-famous case of Ari Folman's 2008 Waltz With Bashir, Bob

Spit sometimes hints at the idea that the “road trip level” of Angeli's

characters may correspond to a “sub-level” of Angeli's psyche. Angeli speaks

(in the film, but also famously elsewhere) of his problems with alcohol, drugs

and sexual behavior. After all, the Kowalskis, the Elton Johns and Bob Spit

inhabit sewers, underground bunkers and tunnels beneath derelict urban

landscapes (even though it’s filled with Easter Eggs, such as the curvy hill of

Mara Tara’s thighs). They cross dilapidated and abandoned streets and roads,

and when finally Bob emerges into Angeli's world, he seems to comes from below

a sofa in which Angeli was sleeping. Were we watching that which Angeli was

dreaming? They seem to touch each other briefly, but Angeli awakes. But soon

enough, while on the elevator, a scene plays out a wonderfully staged crossing

of worlds, as Angeli and Bob Spit finally meet each other. Characters rebelling

against their creators is not necessarily new (Fleischer's Out of the

Inkwell dates back to 1918), and neither is the clash of the different

ontological worlds of creator and created (e.g. Grant Morrison's Animal Man,

or even the 2006 Marc Forster's Stranger than Fiction), but there is

something strangely satisfactory in watching an old familiar character

conquering a different degree of autonomy in relation to both his author and

audience, confirming his contrarian, punkish ethos.

For the people who are knowledgeable

about Angeli's work and these characters, the film offers an opportunity to

re-engage with, and re-interpret it all with hindsight. Is Bob's punkish verve,

the smash-it-all, kicking-against-the-pricks, spit-on attitude still an answer

to society's problems? To apathy? To the sure destruction of the world? To the

idiocy that surrounds us? Now that we are older, that our backs hurt, and that

we don't want to get around much anymore, we may think we don't have the same

energy, sure. But deep inside, just as Angeli in the end leans over his window,

above the anonymous streets below, and spits, we think to ourselves, as

Bob Spit would have said, “Fuck,

yeah!

A version of this review will appear in print in IJOCA 23:2.

~~~~~~~~

Since this material will be unfamiliar to many of our readers, the following is from the movie's press release and a preview is on YouTube :

BOB

SPIT - WE DO NOT LIKE PEOPLE is a stop-motion animation that mixes

documentary, comedy and road-movie. It tells the story of Bob Spit, an

old punk trying to escape from a post-apocalyptic desert that is

actually, a purgatory inside the mind of his creator, Angeli, a

cartoonist going through a creative crisis.The story is freely inspired

by the life and work of one of the most celebrated Brazilian cartoonists

of all times, Angeli, who became famous in the 70s by releasing

political cartoons in the midst of Brazil’s military dictatorship. In

the 80s, he migrated to daily strips, showing an acid sense of humor to

represent Brazil’s society, day-to-day life and customs. Angeli had

editorial success with his monthly magazine “Chiclete com Banana,” which

sold over 120 thousand copies per edition. During his time, the

cartoonist has created some of his most famous characters: the bohemian

diva Rê Bordosa, the hippie pair Wood & Stock, and the punk Bob

Spit.

DIRECTOR’S BIOGRAPHY

Cesar Cabral has a degree

in Cinema through the Arts and Communication School - São Paulo

University (ECA-USP). He began his career as a stop-motion animator in

1998 and co-founded the animation company Coala Filmes in 2000. He

directed the stop-motion short films The Re Bordosa Dossier (2008),

which won more than 70 awards in Brazilian and international film

festivals, and Storm (2010) selected to many prestigious film festivals

all around the world, such as Annecy, Hiroshima, Havana and Sundance.

Cesar created and directed 2 seasons of the young adult stopmotion

animated series Angeli The Killer, selected to 2018 Annecy Film Festival

and broadcasted at Canal Brasil. Bob Spit - We Do Not Like People was

awarded best feature at Contrechamp section in Annecy 2021.

With the voices of Milhem Cortaz, Paulo Miklos, Grace Gianoukas, André Abujamra, Laerte, Hugo Passolo, Angeli.

MILHEM CORTAZ does Bob Spit’s original voice. One of Brazil’s most

exciting actors, he has played parts in films such as “Elite Squad”,

“Elite Squad 2”, “Carandiru” and the DGA nominated "A Wolf at the Door." He has also voiced the character in the series “Angeli The Killer”

PAULO MIKLOS does the characters’ original voice for THE KOWALSKI

BROTHERS, who live in the desert gathering pages of the “Chiclete com

Banana” Magazine. When they meet Bob Spit, they encourage him to find

Angeli. A gifted actor and musician, he played in seminal Brazilian

rock band “Titãs” and had striking parts in films and TV Series such as

“O Invasor”, “Estômago” and “É Proibido Fumar”, “Sessão de Terapia” e

“Os Normais.”

ANDRÉ ABUJAMRA does the characters’ original voice of RHALAH RHIKOTA, a

charlatan guru who had his fame and followers in the 80s. He is the

mentor of the Kowalski brothers. A musician, comedian and actor,

Abujamra has a long story in Brazil’s pop rock scene. He was the

composer of “Carandiru”, and has parts in films and tv shows such as

“Estômago” and “A Grande Família”.

GRACE GIANOUKAS is Rê Bordosa’s original voice. RÊ is a junkie diva

who was the most famous of Angeli’s characters. The cartoonist killed

her in the 80s, and since then she is a lingering presence in his life.

An actress, director, screenwriter and producer, she had several roles

in theatre, TV and cinema. She is currently starring in the TV Globo

soap opera “Orgulho e Paixão”.