reviewed by Philip Smith

Horror Comics and Religion: Essays Framing the Monstrous and the Divine, edited by Brandon R. Grafius and John W. Morehead, McFarland and Company, 2025. 275 pages. $49.95. https://mcfarlandbooks.com/product/horror-comics-and-religion/

Horror Comics and Religion is divided into four sections: ‘The Classics,’ ‘To Hell and Back,’ ‘Beyond Marvel and DC,’ and ‘Breaking the Frames.’ The section divisions seem somewhat arbitrary; the section titled 'Beyond Marvel and DC', for example, does not include the chapter on Monstress (2015-), which is published by Image. The section 'Breaking the Frames' could, in the sense of challenging norms, reasonably house any of the chapters in the volume.

The introductory chapter lays out the terrain primarily in formal terms; horror leverages our emotions through implication; comics use a different language from film because the creator cannot control the speed at which a consumer accesses an image; and comics cannot directly replicate the glimpse of a source of horror as we find in film. In the first chapter, Wetmore argues that EC's horror comics include forms of ironic justice which parallel Christian morality, but meted out by reanimated corpses rather than a Christian God. The forms of punishment are, inevitably, violent, such that the reader is invited to revel in body horror even as justice is done. The second chapter concerns the problem of representing the holy, monstrosity, and the rhetoric of religious justice through the superhero the Spectre. The character, Dean argues, 'is an American answer to criminal evil that is less interested in origins or grand schemes as it is in punishment for moral transgressions being met with the individual creativity of an avenging, nigh-omnipotent angel-cop' (50). The third chapter uses Walter Benjamin's Capitalism and Religion (1921) as a lens to examine From Hell (1989). The argument is persuasive, but Greenaway tends to assume a degree of familiarity with the primary text, making the argument hard to follow at times. McGuire and Possami's chapter, concerns the depiction of exorcisms in comics. Chireau draws upon a range of (in many cases previously unexplored) texts and links mid-twentieth century comics to coeval media. The chapter persuasively demonstrate that the depiction of Voodoo in Golden Age horror comics embodied contemporary anti-Black racism.

In the second section, Holdsworth uses a framework of Biblical and Christian writings concerning parent-child relationships to argue that Gaiman's depiction of (fallen) angels in The Sandman (1999-2015) series suggests a Creator who is 'too powerful to be a healthy human father and too fallible to be a divine one' (121). Gaiman's Lucifer, she asserts, is 'a twisted Peter Pan figure - an eternally abused child with no way to grow up' (122). In the seventh chapter, Foster uses a Christian reading of René Girard's mimetic theory to interpret Ghost Rider: The War for Heaven (2019). FitzGerald approaches Monstress through Eduardo Viveros de Castro's concept of 'multinatiralism'; an understanding of animality as connected to and in dialogue with humanity, Taussig's concept of 'subjecthood', Kristeva's abject theory, and some Foucault. The ultimate conclusion is that Monstress blurs distinctions between self/other, human/animal, and mortal/divine, although the path to this conclusion is, at times, hard to follow and would have benefitted from more signposting. (The four pages of footnotes which follow further suggest that the argument needed tightening).

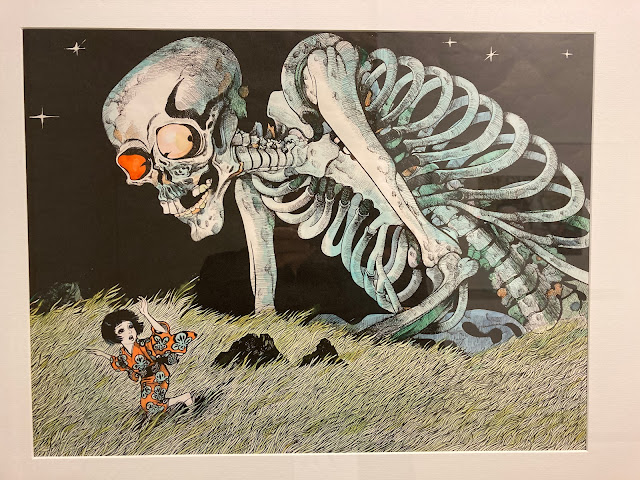

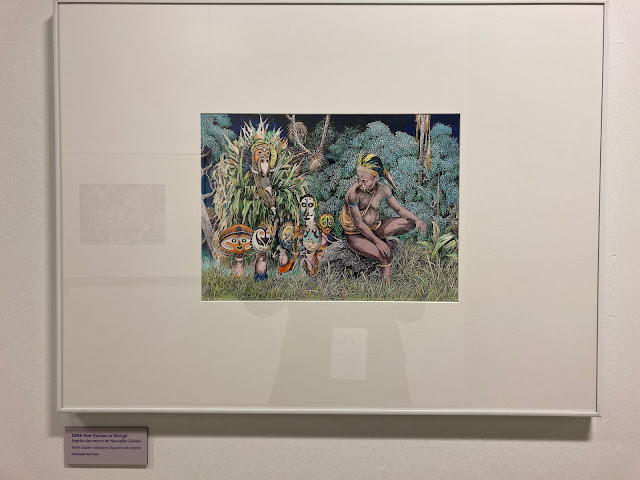

In the third section, Akagi analyses the blurring of distinctions between life and death in the manga series Another (2009), which he contrasts with passages from Revelations. Cowan argues that Junji Ito's horror manga express a logic which aligns with a religious world-view. Mukhopadhyay's essay on the (mis)representation of tantrik in popular culture is a useful introduction to the actual practice of tantra and the ways in which popular portrayals represent a misunderstanding. The discussion of City of Sorrows (2014-2018) as a counter to such discourse, comes a little late in the chapter but is nonetheless illuminating.

In the final section, Cooper analyses Angle's The Devil is a Handsome Man (2018-2019) in terms of the abject, in particular body horror related to the eyes. Meletiadis writes on Jeff Lemire's Gideon Falls (2018-2020) through the idea of the ineffable as expressed through Manichaeism, Gnosticism, and Lovecraftian cosmic horror (although he asserts of the chapter 'there is no overall argument here' (233)). Anderson reads the Biblical references in Emily Carroll's His Face All Red and My Friend Janna (2014), arguing that Carroll destabilizes Christian imagery (Cain and Abel, the Resurrection and so on) and spiritualism as an uncanny warning against upsetting the conventional order.

Overall, I found the book to vary in quality; Chireau's chapter on Voodoo ('a horror conceived by whiteness' (90)) is specific in its scope and well-argued. Anderson’s chapter is similarly illuminating. Other chapters are weaker; FitzGerald's chapter on Monstress and Meletiadis' chapter on Gideon Falls are needlessly fawning of their subjects employing phrasing such as 'quintessentially, irresistibly, deliciously uncanny' (143) and 'a virtuoso performance' (231). Such overblown praise, I would argue, adds little information, gives up any pretense of scholarly objectivity, and asserts overtly what might otherwise be suggested through the argument. McGuire and Possami's chapter seeks out trends in the depiction of exorcisms in comics, seeks to find a consistent message between works from a diverse range of sociocultural contexts and genres (horror, superhero, science fiction, the 1970s, the early twenty-first century, America, France, and Japan). The conclusion that 'in the comic book narratives, the supernatural exorcism is more often successful if conducted by a [sic] exorcist with individual charismatic power' (83) risks collapsing the differences between these linguistically, culturally, and historically discrete works.

The volume largely cleaves to the orthodoxy that horror comics are inherently subversive (e.g. 'EC comics subversively critiqued middle-class morality' (20)). At points, however, authors show some tendency to challenge this idea; Wetmore notes that justice in EC comics is generally retributive; a violent reinforcement, rather than critique of, mid-twentieth-century white American Christian morality. Elsewhere in the volume, Chireau argues that while EC and those who followed offered 'subversive treatments of religious bigotry and racial prejudice' (98) they nonetheless depicted 'the threat of religious contagion [...] and the impacts of racial transgression on ethnically compromised white Americans' (99).

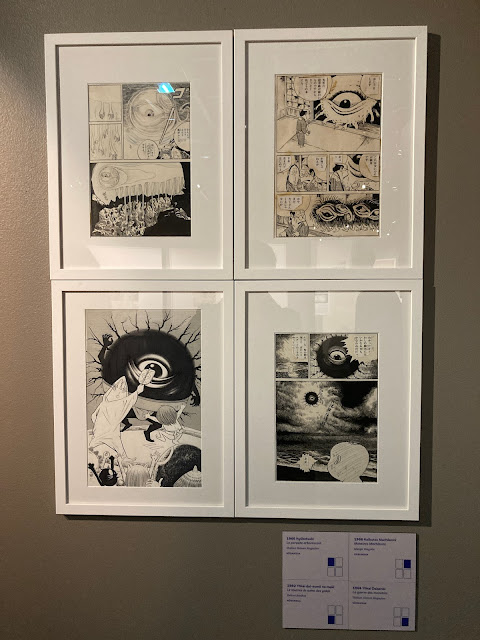

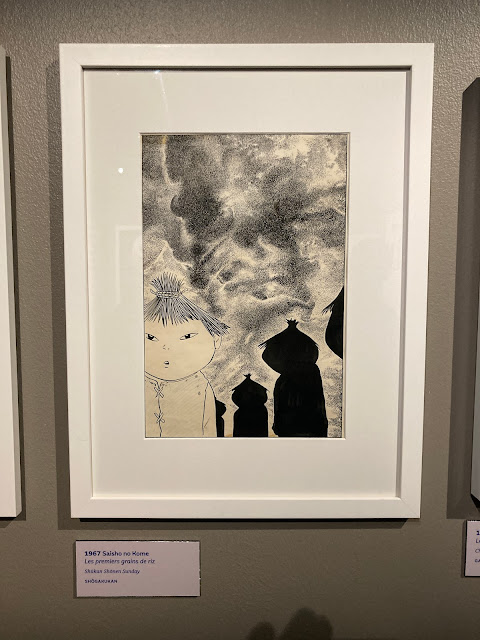

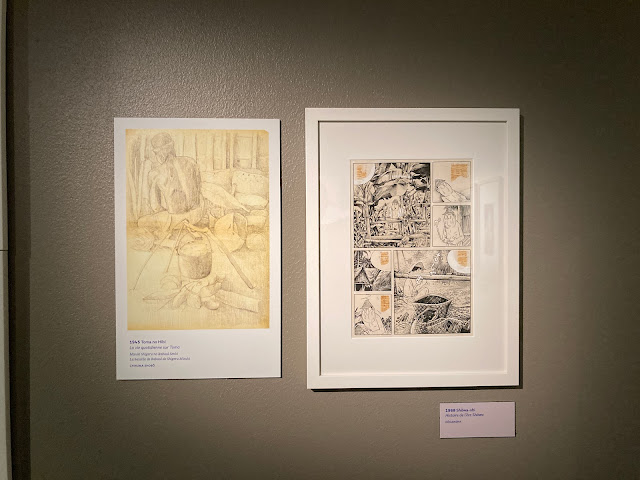

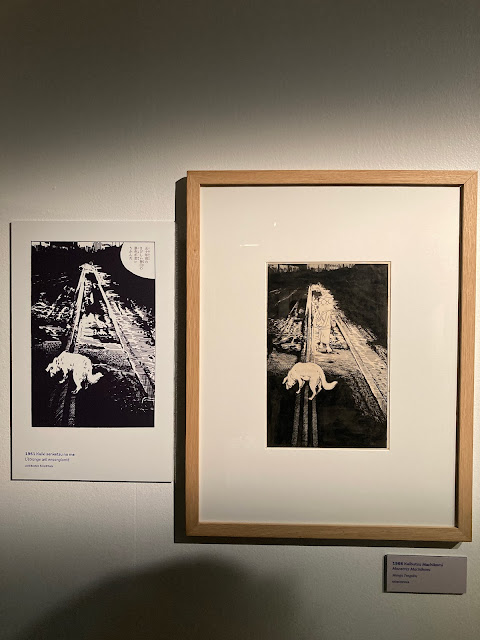

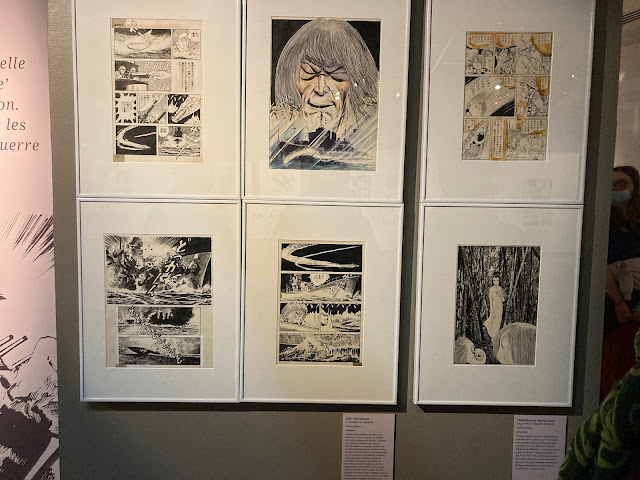

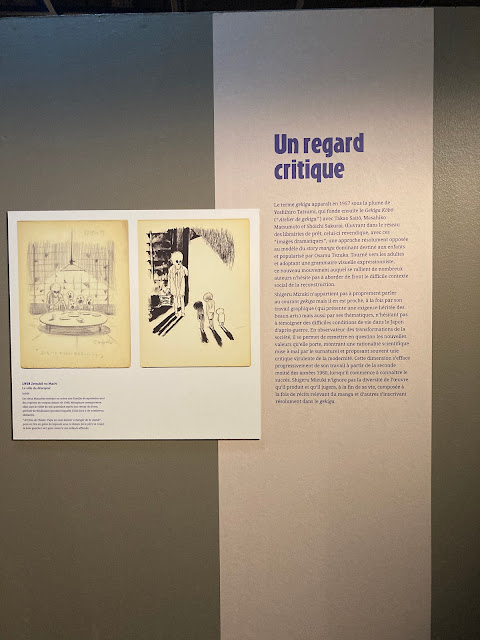

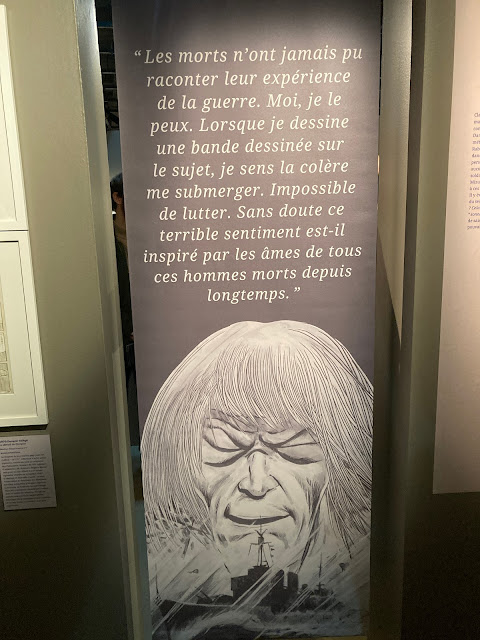

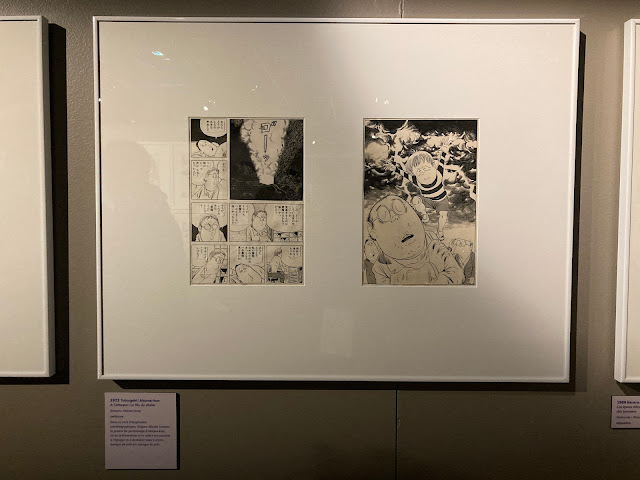

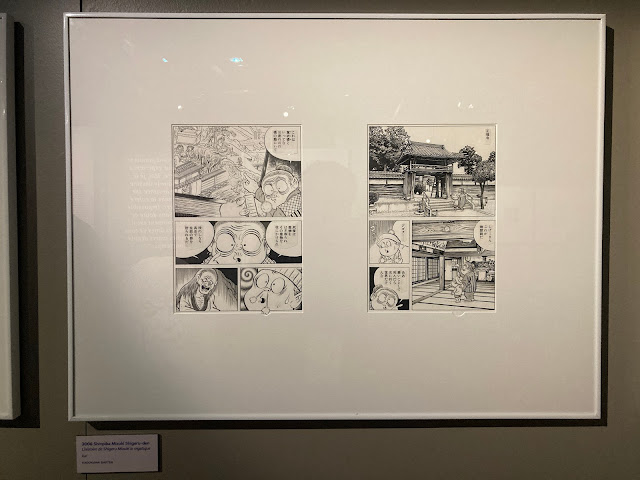

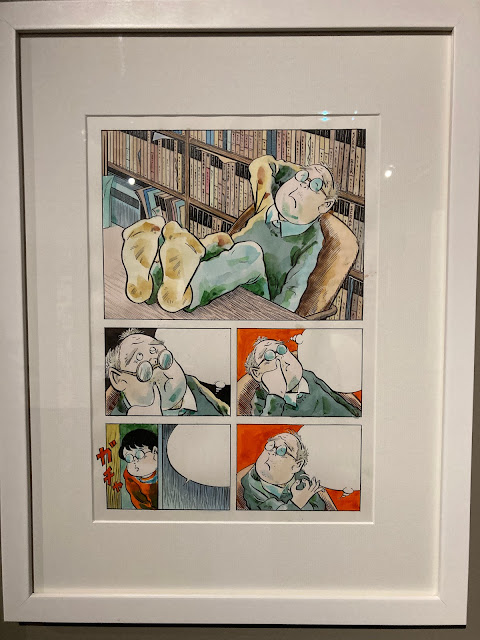

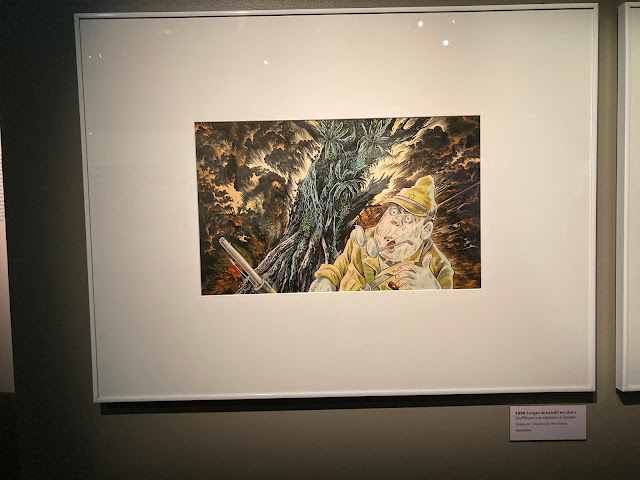

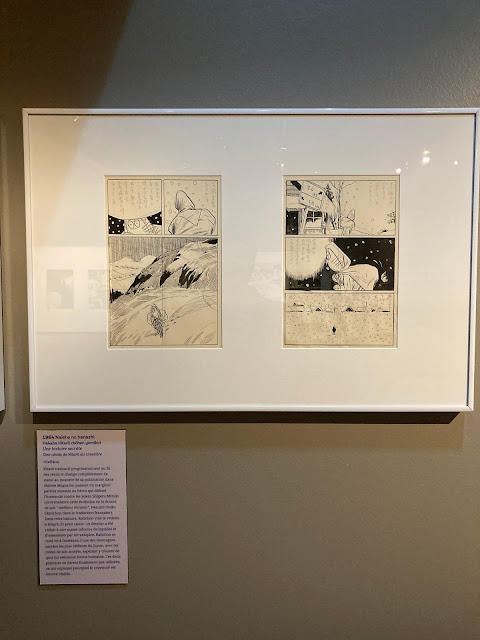

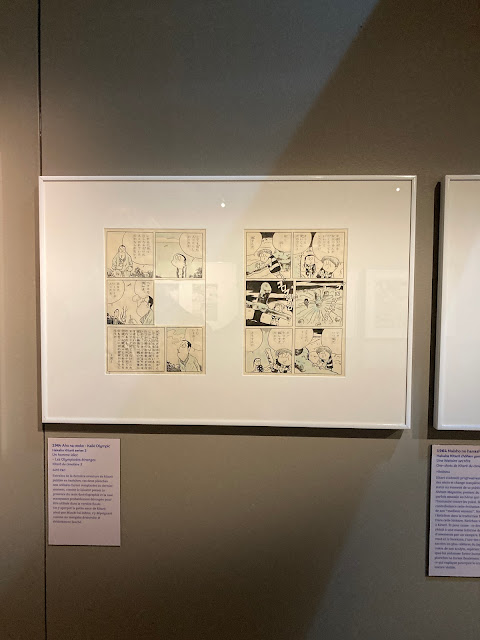

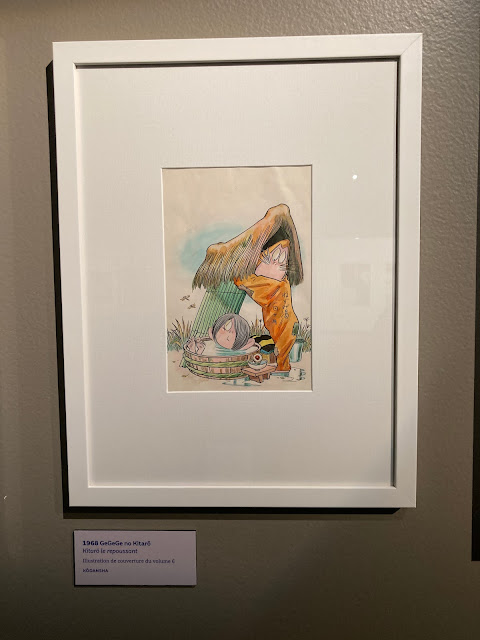

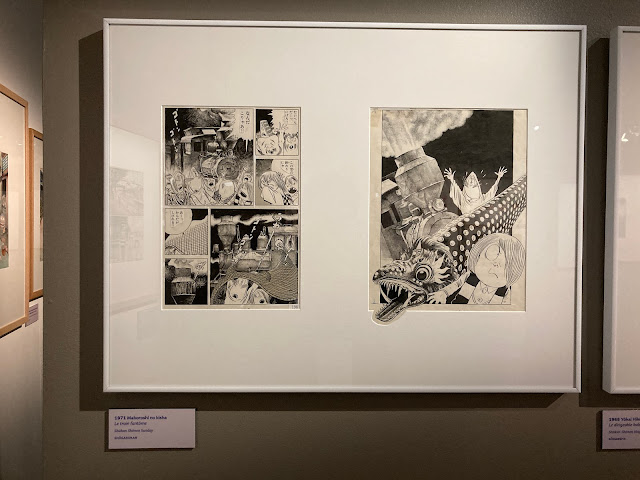

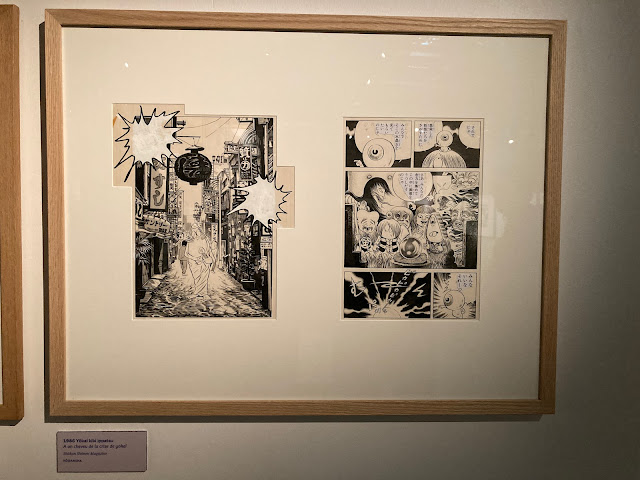

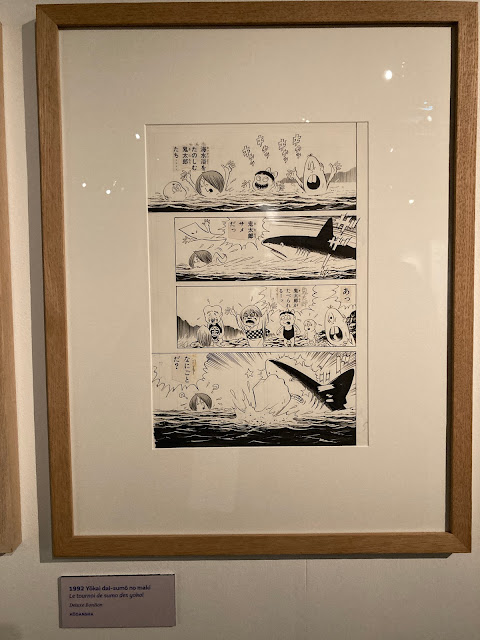

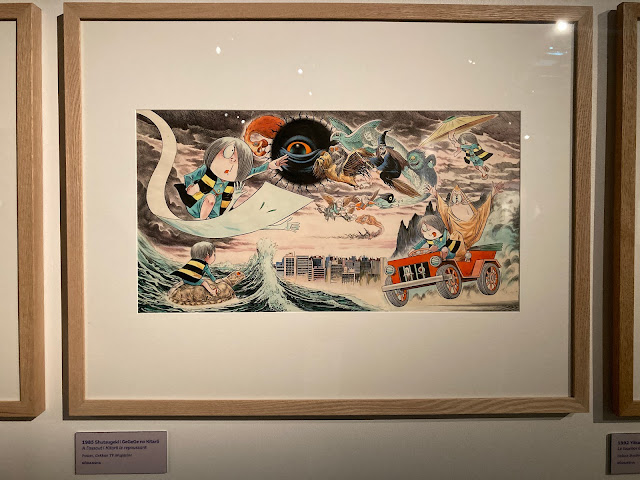

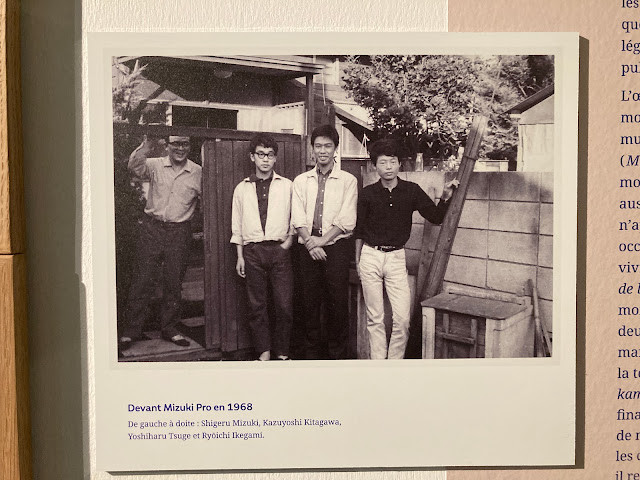

The greatest weakness of the volume is the apparent lack of editorial polish manifest in typographical errors such as 'Of course, the is true...' (48), 'people have since that time have become...' (80), and 'non-vegetarian food, especially fish and meet' (206). There are also several difficult to parse sentences such as 'These techniques, while extending to the presentation of several characters, appear most extensively in the portrayal of Misaki and Sakakibara and may be considered according to these two characters to illustrate.' (162). These errors do not wholly invalidate the often insightful and original arguments, but they are distracting and suggest too light an editorial hand. They also weaken the authority of the volume; the lack of care which gives rise to typographical issues may suggest similar weaknesses in scholarship. Indeed, Cowan's assertion that Junji Ito's works are 'less well-known in the West' (177) jarred with my own experience in Angoulême in 2023, when I witnessed hundreds of Western comics fans queueing in the cold for hours so they could see Ito at work.

Philip Smith is the author of Reading Art Spiegelman (Routledge 2015), Shakespeare in Singapore (Routledge 2020), and co-author of Printing Terror: American Horror Comics as Cold War Commentary and Critique (Manchester UP, 2021). He has served as co-director of the Shakespeare Behind Bars program at The Correctional Facility at Fox Hill, Nassau, Bahamas, fight choreographer for the Shakespeare in Paradise festival, and an executive board member for the Comics Studies Society. He is Chair of Liberal Arts and Professor of English at Savannah College of Art and Design. He is editor in chief of Literature Compass.