|

|

Articles from and news about the premier and longest-running academic journal devoted to all aspects of cartooning and comics -- the International Journal of Comic Art (ISSN 1531-6793) published and edited by John Lent.

|

|

| ||

fig 1

|

a review by Mark McKinney (Miami University, Oxford, Ohio)

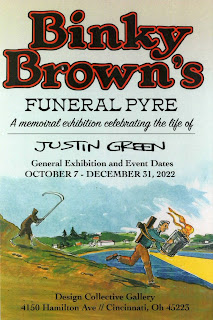

As the exhibition's title indicates, visiting Justin Green's Funeral Pyre allows visitors to celebrate and mourn Justin Green. [FIGS 1 + 2] The artist died in Cincinnati at age 76 of colon cancer on April 23, 2022, according to his obituaries in several prominent periodicals, including the Chicago Tribune, The Comics Journal and The New York Times. Justin Green is best known for his autobiographical work Binky Brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary, first published by Last Gasp in 1972, and cited by Art Spiegelman as having inspired him to write Maus. The exhibition's organizers are Carol Tyler and Julia Green. Tyler, his wife, is an accomplished cartoonist specializing in biographical and autobiographical comics, and is therefore uniquely qualified to represent Justin Green's art and life. So is Julia Green, their daughter, who is both an artist and owner of the gallery hosting the exhibition. The exhibition allows the visitor to remember Justin Green in tangible ways, and to celebrate the art he has left behind, both through the content and structure of the exhibition, and the stories that Tyler and Julia Green tell about him and his art. Design Collective Gallery is located in Northside, a neighborhood northwest of downtown Cincinnati that is known for its openness to the arts and popular music. For example, just a few doors down from the gallery lies a local landmark store, Shake It Records, which has a large stock of vinyl disks, a comics section in the basement, signs painted by Justin Green, and original artwork by him on the walls, especially full-page comic-strip biographies he drew for Pulse! magazine, published by Tower Records. The Design Collective Gallery, with its painted graffiti mural on the outside of its north wall, and this exhibition, fit seamlessly into the neighborhood. The gallery's front glass windows are decorated with large black-and-white characters from comics by Justin Green. [FIG 3] The exhibition opened on October 7, 2022 and runs through December 31 of this year, in Design Collective Gallery (4150 Avenue, Cincinnati, Ohio). It is open from four o'clock in the afternoon to seven o'clock in the evening on Thursdays, Fridays and Saturdays, or by appointment). On entering the gallery, visitors are greeted by Tyler or Julia Green, who kindly give tours of the exhibition. I visited it on Thursday, December 8, 2022, and was given one.

| |||

| fig 3 | |

| ||

fig 4

|

The exhibition is organized into approximately six sections, organically grouped by themes, but without a strict chronological progression or complete thematic separation between them. Two large rooms, each of which contains a section of the exhibition, are separated by a center wall running most of the building's length, with an open doorway midway that allows passage between the two. The long left or north room, the first space when one enters the gallery, is titled "The Underground," after Justin Green's underground comics. [FIG 4] Julia Green said that the room contained about one sixteenth, at most, of his underground comics originals, and that the family owns only three pieces of that work, because her father had sold, traded, or given away almost all of it. However, thanks to the generosity of current owners of the original art, several important pieces are part of the exhibition. Moving clockwise around the room, beginning at the northwest corner of the building, one first sees the photograph that helped inspire Green's comics collection Sacred and Profane [FIG 5] (it is also reproduced on the inside front cover of the book). Taken by Keith Green, the artist's brother (who died in 1995), it shows a sign in the form of a saw, advertising a store in San Francisco, seemingly laid across the lower part of a cross that advertises a different, religiously affiliated, building, as though the tool were sawing iconoclastically through the symbol of Christ's crucifixion. [FIG 6] The photograph inspired the artist's work on the comic book, Julia Green told me. Beginning just to the right of the photo, and stretching across most of the rest of the north wall, a large painting of a building borrowed from the front cover and page three of Sacred and Profane artfully frames reproductions of the pages from all five installments of "We fellow traveleers" [sic] anthologized in the Last Gasp book, after serialization in Comix Book, a series published by Marvel and Kitchen Sink Press. [FIG 7] Librarians at the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library and Museum, at the Ohio State University, generously scanned the original art, held in their collection, so that high-quality reproductions of the pages could be displayed here. At the end of the sequence, in the corner, is original art from the "Rowdy Noody" page on the back cover of Sacred and Profane, and related originals, including the front cover illustration of Comix Book no. 5 (cf. the last panel of "We fellow traveleers: conclusion," part 5).

|

| fig 6 |

|

| fig 7 |

|

| fig 8 |

|

| fig 9 |

The right-hand side of the back wall features a large reproduction of the famous frontispiece drawing of the naked, chained and suspended narrator of Binky Brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary. [FIG 8] Visitors are invited to write down a title from a bibliography that lists Justin Green's comics and post it in the remaining blank wall space, so that a wall full of Green's titles appears to emerge from the pen of his tortured self-portrait as Binky Brown. Against the back half of the room's south wall are a display case and a long, hung frame containing sketches, letters and notebooks that document Green's art and his relationship to it. [FIG 9] Among them is a letter in his beautiful calligraphy that he wrote in1975 to

|

| fig 10 |

Albert L. Morse, the man who had purchased all the original art from Binky Brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary (1972) for twelve dollars per page, amounting to just over five hundred dollars for the forty-two pages. [FIG 10] In his letter, Green bitterly expresses his belief that he had been exploited by Morse through the sale, and should receive further compensation from the buyer for his artwork.[1] The artist suggests that personal problems, including the state of his mental health, were factors leading to him accept such a small amount of money for his autobiography. Julia Green explained to me that her father had sold the art to Morse in order to be able to pay his rent. Together, these artifacts document Justin Green's artistic creativity, his struggle to bring his comics-related projects to fruition, and his conflicted relationship to the sign-painting that he began in San Francisco, before moving to Cincinnati in 1997 and continuing to work in that profession. The latter was both a source of autonomy, because it enabled him to pay his bills, and of frustration, insofar as it prevented him from working fulltime on other creative projects, such as his comics.[2]

|

| fig 11 |

|

| fig 12 |

|

| fig 13 |

On the front half of the same wall hang several pieces of original art by Green: a page from the "Projunior" series, a casket sculpture, "Zen time" (two single-page stories, including the one from the inside back cover of Sacred and Profane), "The graduate" (one page), two Philip Morris tobacco advertising parodies, and two versions of a Colonel Sanders parody page published on the inside back cover of Green's Show + Tell Comics. [FIG 11] Julia Green intentionally positioned the Colonel Sanders parody pages near the front of the gallery so that when one stands inside the building looking out through the front window, the Kentucky Fried Chicken restaurant and its Colonel Sanders sign located just across the street are visible simultaneously with Green's parodic drawings of the advertising icon. [FIG 12] Although the drawings, which show a blood-stained Colonel Sanders slaughtering chickens with an axe, might seem to suggest otherwise, Julia Green said that her father was not a vegetarian. She also said that he had smoked cigarettes even though his parodies refer to the deadly effects that smoking can have. The casket sculpture appears to symbolize part of Justin Green's

|

| fig 14 |

attempt to exorcise the weight that his Binky Brown series ended up representing for him.[3] [FIG 13] Tyler and Julia Green opened the casket to show me what they had put inside. The material includes a photograph of the casket at their home in California, before he shipped it to Ron Turner at Last Gasp comics. At the inside top of the casket, they placed a pen-and-ink drawing by Green of a naked woman crouched atop two bound books, reaching out to touch a human skull. [FIG 14] Tyler told me that the woman could represent her or Julia Green reaching out to touch the dead artist, and kneeling on top of his art work. Below the drawing is a two-page letter by Tyler to her husband, dated March 27, 2020, and asking him for some of the basic documentation helpful to loved ones after a person's death: preferences for distributing personal possessions, passwords for bank accounts, and so on. An uncompleted, official-looking form for writing down one's "Last Will and Testament" is attached just below. Right under that is perhaps the artist's last drawing, done in red pencil on a yellow legal pad: a smiling face – of a ghost? – and an arrow facing downward, as though the answer to Tyler's request for Green's last wishes might be found below. However, she told me that her husband left no will or final directives. Instead of a last will and testament, he left a final joke.

|

| fig 15 |

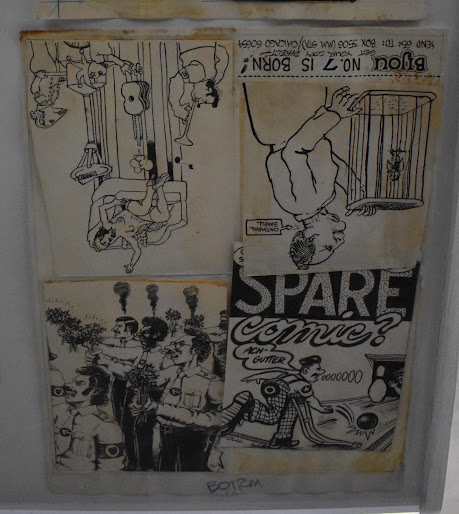

Justin Green's contribution to the early history of minicomics is featured through original art in the display case standing in the center of the room. [FIG 15] In his homage to the late artist, comics historian Patrick Rosenkranz states that "Justin Green's Spare Comic… initiated the mini-comic genre, along with 'Jud' Green's Underground Cartooning Course."[4] Artwork for both of those minicomics is included here. [FIG 16] Julia Green explained to me that her father would take his minicomics art to a Kinko's store to reproduce it on photocopy machines. Another minicomic in the exhibition recounts the birth of Julia Green through the narrative of a stork character flying to various addresses where her parents had lived, before finally finding them in the San Francisco General Hospital and passing out on the floor, after having delivered the baby to her happy parents, shown together with her in a photo.

|

| fig 16 |

|

| fig 17 |

|

| fig 18 |

|

| fig 19 |

|

| fig 20 |

Just behind the long room with "The Underground" section are several small exhibition spaces. They are set up in a way that recalls living history museums, often associated with urban or rural working classes, or else living spaces of the rich that are preserved in fine art museums. These are, in fact, shrines, carefully and lovingly reconstructed by Tyler and Julia Green, just as is, of course, the entire exhibition. One of them, titled "Inner Sanctum," reconstitutes the artist's living space in his final months, but also evokes his entire life. [FIG 20] It includes Green's plaid shirts arranged on a wall, around one of several mandelas that he painted close to the end of his life to try to cope with his illness and his mortality. [FIG 21] On the floor lie his paint-stained clogs. His guitar is propped up against an armchair. [FIG 22] Tyler told me that she had placed the urn with Green's ashes on the chair for a memorial ceremony. During the event, family members brought and laid on it, next to the urn, personal objects with special meaning for the artist and his life, such as a drawing he made as boy that symbolized his lifelong desire to follow his own path, which was opposite from that of others. A printed page with the ceremony's order of events rests on a filing cabinet. Above the armchair hangs a self-portrait that Green painted while in high school. His books and personal photos sit on a bookcase and shelves. On a wooden stand lies a hot plate on which he heated up substances contained in labeled bottles and cans, concoctions with which he tried to cure himself of the cancer that finally killed him, as Tyler explained to me.[6] [FIG 23]

|

| fig 21 |

|

| fig 22 |

|

| fig 23 |

|

| fig 24 |

Outside the "Inner Sanctum," in a hallway leading toward the gallery's back room, is a display case with samples of Green's calligraphic work, made for a friend. In other display cases and attached to the wall are dozens of pieces of original artwork by Green, for a myriad of projects, ranging from Binky Brown stories to his Pulse! magazine work, and projects for cartoons and comics. [FIGS 24, 25] One, a cover illustration for a projected but never published collection of drawings, is titled "Notes before closing time, Justin Green, Cincinnati, 2009." On it, the grim reaper's reflection appears in a mirror, startling the artist, who is sitting at the counter of a bar or a diner. [FIG 26] Tyler told me that he was always thinking about death. Green's sign-painting work is also featured prominently in this area. Artifacts include a sign he made to advertise his sign-painting business, and sketches for signs he made for others. The last sign he painted, for the bathroom in Julia Green's gallery, is at the end of the hall, around the corner.

|

| fig 25 |

|

| fig 26 |

|

| fig 27 |

At the very back of the gallery, in a large workshop or storage area, lies another installation. [FIGS 27, 28] It reconstructs a scene that Justin Green painted: a pastiche of The Art of Painting (or The Allegory of Painting; circa 1866–8). The latter is a self-reflexive representation of the art of painting – a self-portrait of the artist in the process of painting a woman's portrait – by Johannes Vermeer van Delft.[7] Green made his version, depicting "a small sign shop somewhere between the Vietnam Era… and 1986," to illustrate the front cover of the October 2001 issue of Signs of the Times, a national sign-painter's monthly magazine based in Cincinnati, to which he contributed a comic strip for years. [FIG 29] Through his own self-reflexive image, Green asserts that sign painting and cartooning are both arts, just as was the work of the Dutch old master. Tyler and Julia Green both described Justin Green's masterful sign painting skills for me. His former partner from his sign painting business in California helped create the installation for the gallery, including by printing the large backdrop behind it. A poster version of Green's page is available for sale from the gallery. Tyler told me that her husband had asked her to have copies printed as presents for the caregivers at the hospice where he spent his final days. A copy of the poster is attached to an easel set in front of the built installation, so that one may view together, in a meta-representational mise-en-abîme, both the poster and the (rest of the) installation, which reproduces the scene that Green depicted in his illustration.

|

| fig 28 |

|

| fig 29 |

|

| fig 30 |

|

| fig 31 |

The remaining installation is titled "The Studio." Situated across the hallway from "Inner Sanctum," it is itself another self-reflexive artistic work, and also again contains one. The installation recreates Justin Green's cartooning workspace, which Tyler and Julia Green took from home and reassembled in the gallery. [FIG 30] It is a three-dimensional mise-en-abîme that incorporates a two-dimensional one: original art drawn by Justin Green and referring, like "Notes before closing time," to his impending death. On his own wooden easel, below his desk magnifying glass, its light still on, sits a half-finished illustration, as though he had just stepped away from his work. [FIG 31] As Julia Green pointed out to me, the image is exceptional in terms of her father's usual creative process, because instead of being wholly at one stage – say, the pencil rough, or the page then being inked, or colored – it combines various stages. The illustration's title and image suggest that this was entirely intentional, and that the artist meant it to be his final artistic statement. The title is "The last will and testament of Binky Brown, by Justin Green." Just as does the installation in which it is set, the image represents Green's drawing studio, with his easel and chair, pens and inks, paintbrushes and paints. The lower part of the image, still in the pencil rough stage, depicts the artist seated at his desk, with a mostly empty thought balloon above his head. He is turning around, because he is being called away right in the middle of his work. "Let's go, pops!" says a thin, skeletal figure with a scarf around its neck, standing behind the artist. This is clearly death summoning Justin Green before he has completed his final project, perhaps an anthology of his comics, something he had imagined doing but was never able to complete. We might also view the illustration as a reflection of the artist's relation to the entire exhibition itself, which – Tyler and Julia Green have said – he had hoped to see through to completion before his death.

|

| fig 32 |

According to Julia Green, it was her father who titled the exhibition "Binky Brown's Funeral Pyre."[8] This meta-artistic statement must be yet another self-aware irony of Justin Green, to which those he left behind have given form. If a funeral pyre involves heaping personal effects in a pile and lighting them to feed a fire that cremates the deceased, here, instead of being piled up and burned, those effects are exhumed and laid out carefully in sequences. They are relics of the dead artist, carefully and lovingly arranged so that the living may both mourn and celebrate him. In fact, Tyler told me that she is currently making a book about mourning. While I visited the exhibition, listening first to Julia Green and then to Tyler tell me about the artist's life and work, family friends came in, viewed the exhibition, and chatted with them. Recordings of Justin Green playing the blues on his guitar provided background music in one of the rooms. To visit the exhibition, and to listen to his wife and daughter speak about him, is be able to participate, empathetically, in a kind of ritual, both sacred and secular, in something like a wake for the dead artist, someone who made tremendous artistic accomplishments, despite suffering enormous pain throughout his life, because of his anxiety and obsessive-compulsive disorder. The exhibition teaches us much about Justin Green's life and art, but we will soon be able to learn even more. Carol Tyler and Julia Green are planning publications of Justin Green's Binky Brown series and other comics, sketches and notes, correspondence, and no doubt much more. [FIG 32] A book biography of the artist by John Kelly is in the works, as is Married to Comics, a documentary film by John Kinhart about Carol Tyler and Justin Green, with a release planned in the near future.

The author took all the photographs that illustrate this review. The art and installations in the illustrations are all © the Estate of Justin Green. Any republication of the photographs requires prior authorization from the author and from the executors of the Estate of Justin Green.

References

Green, Justin. 1976. Sacred and Profane. Berkeley: Last Gasp.

Green, Justin. 2009 [first edition 1972]. Binky Brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary. San Francisco: McSweeney's Books.

[1] In his acknowledgments at the end of the McSweeney's edition of his book, Justin Green wrote: "In addition to those lauded in the afterword, the late Albert Morse should be thanked for squirreling away in his garage the original Binky art, which he bought for a song back in '73. That disavowal ironically preserved the art intact. His surviving mate and caregiver Christine Valenza kindly authorized the use of the original work for this publication, without asking for a lousy dime."

[2] See also the conclusion of "Sweet void of youth with Binky Brown," in Sacred and Profane.

[3] An online tribute to Justin Green explains the coffin's history and meaning: "In 2005, Green sent this small, handmade coffin to Last Gasp’s Ron Turner. To Turner, it indicated that Green had some future literary plans to kill off—bury and finally shed off—his most famous creation, much in the same way Robert Crumb killed off Fritz the Cat with an ice pick," in John Kelly, "Remembering Justin Green," The Comics Journal, 8 June 2022, https://www.tcj.com/remembering-justin-green/; accessed 10 December 2022.

[4] Patrick Rosenkranz, "Justin Green, 1945–2022," The Comics Journal, 30 April 2022, https://www.tcj.com/justin-green-1945-2022/; accessed 10 December 2022.

[5]

Kelly, "Remembering Justin Green." The Comics Journal,

8 June 2022, https://www.tcj.com/

[6] See also Tyler's statements quoted in the following articles: Rosenkranz, "Justin Green, 1945–2022"; and Christopher Borrelli, "Justin Green, a pioneer whose Highland Park childhood led to a new confessional kind of comic, dies at 76," Chicago Tribune, 29 April 2022, https://www.chicagotribune.com/entertainment/ct-ent-justin-green-comics-obituary-20220429-fq2nxm67r5ewtdnu7nvt7ceyui-story.html; accessed 10 December 2022.

[7] In the collection of the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna; https://www.khm.at/en/objectdb/detail/2574/; accessed 10 December 2022.

[8] In Kelly, "Remembering Justin Green."

Reviewed by Viola Burlew

Sean O’Connell. With Great Power: How Spider-Man Conquered Hollywood During the Golden Age of Comic Book Blockbusters. Essex, Connecticut: Applause Theater and Cinema Books, 2022. http://applausebooks.com/books/9781493066193

There is perhaps no more iconic character in the Marvel universe than Spider-Man. Over the course of sixty years, various creative teams have depicted the web-slinger as an “everyday” superhero, from the first of his kind to his present-day status as a figurehead of the type. To examine the impact the character has had on superhero culture requires examining the intricacies of multiple versions of the character in print and digital media alike.

Sean O’Connell’s With Great Power… achieves this feat and more. O’Connell’s work follows the growth of Spider-Man from a comic book fill-in feature to the big screen’s friendly neighborhood, billion-dollar-generating hero.

Decade by decade, he analyzes how different adaptations of Spider-Man have shaped both the character and the superhero film industry itself. He works his way from the 1960s to the 1990s in the book’s earliest chapters, demonstrating how repeated production failures adapting Spider-Man indicated a general apathy towards the comic book film genre. These early attempts to create an on-screen hero lacked a recognizable comic book feel, an element O’Connell argues is necessary to have a successful, and faithful, adaptation, in part due to technological limitations. Financial and licensing issues played their own part in delaying Spider-Man's appearance on the big screen, as O'Connell further details in his discussion of James Cameron's unproduced Spider-Man film of the 1990s. As a result, it is not until the 2000s that a Spider-Man appears with any kind of memorability on the big screen.

It is from this moment forward, with the development of Sam Rami’s Spider-Man films, that O’Connell can truly delve into the complexities surrounding the on-screen character and subsequent adaptations. O’Connell’s close analyses of Tobey Maguire, Andrew Garfield, and Tom Holland’s depictions of the character, coupled with detailed accounts of Sony and Marvel’s bargaining over Spider-Man’s rights and marketability, reveal just how crucial Spider-Man was to the creation of the now-popular superhero universes. Strikingly, O’Connell does not pit these films against one another in his analysis. Instead, he traces their progression up to the present day, arguing that each Spider-Man product is a worthy successor to that which came before it. Though he clearly outlines certain missteps, his arc of Spider-Man media points to a consistent rise in quality, with each new film meaning something different to its creators and, crucially, its audience.

While the book is a chronological approach to Spider-Man’s development, O’Connell also offers readers a brief history of the superhero film market itself. He argues that Spider-Man has long been at the center of the genre’s development, with production companies seeing Spider-Man as the character that would launch a great wave of superhero films and sequels. In building these stories around a single character, O’Connell demonstrates that Spider-Man not only “conquered” the blockbuster golden age, but that the genre grew out of and around him.

With Great Power clearly demonstrates O’Connell’s passion for Spider-Man’s character and history. One of the text’s great strengths is O’Connell’s ability to tell these stories with a touch of personal flair—not a bias that privileges one adaptation over the other, but a fondness that seems to stem from genuine care for the character’s legacy. His interest in Spider-Man as a fan could be expanded upon; an occasional weakness of the text is the cursory nature of fan community responses, which undercuts O’Connell’s discussion of Spider-Man reboots and recasting. But this absence is largely secondary in examining the overall depth of O’Connell’s work and his apparent affection for Spider-Man.

This affection is precisely what makes for the most powerful portions of the text. O’Connell shares not only his own personal identification with Spider-Man, but others’ identification as well. He references Rami’s personal connections to Spider-Man, Garfield’s great love of the character, and Holland’s attachment to the role. These moments, in which creative teams find themselves reflecting on their personal relationship with the character, provide the evidence for O’Connell’s richest claim: that “Spider-Man belongs to everyone, and he belongs to no one.” (129) As much as Spider-Man legitimately belongs to the corporations who have battled over him, O’Connell emphasizes that Spider-Man also “belongs” to those that see themselves as embodying some element of his character. Their attachment to him gives them stake in his narratives, in the pieces of themselves they see reflected into him. When these are the individuals creating Spider-Man narratives, this fondness of him is what O’Connell sees as part of each adaptation’s success. While corporations create the need for constant creation and remakes, Spider-Man is at his best when he, even for a moment, “belongs” to someone who cares about his history and his legacy.

This guiding ideology shapes With Great Power into a character study predominantly about the power of connection and personal truth in adaptation. These emotional moments of recognition, shared among Spider-Man’s many makers, are what make the character truly great. O’Connell reflects on this in his final discussions of the most recent Spider-Man adaptations, Into the Spider-Verse and No Way Home. These final films emphasize the hero’s place among a vast multiverse, where many Spider-people, and Spider-creators, can find themselves reflected in the character’s story. O’Connell concludes his analysis here, with two overarching takeaways: Spider-Man’s history is fascinating, and his legacy is powerful.

Overall, O’Connell weaves an intricate web through the superhero movie genre with Spider-Man constantly at its center. With Great Power deftly demonstrates not just the power of the superhero film, or the power of a classic character, but the potential for greatness still to come from a character that wields as much power in our universe as he does in his own.

reviewed by Martha Kennedy

Chris Ware. Julien June Misserey and Benoît Peeters. Paris: Bibliothèque publique d’information, June 8-October 10, 2022. www.bpi.fr/exposition-chris-ware-bpi/

An outstanding exhibition

that featured the work of Chris Ware ran June 8 – October 10, 2022, at the Bibliothèque publique d’information (Bpi) at the Centre Pompidou in Paris. It was developed in

partnership with the Angoulême

International Comics Festival, which honored him with the Grand Lifetime

Achievement Award in June of 2021. The exhibition, developed in close

collaboration with Ware, celebrated his prodigious talent and inventiveness in

comics, an area in which he has pushed expressive and formal boundaries. Prior

to this major international honor during his nearly 40-year career, Ware had

already received many other prestigious awards including: several Ignatz,

Harvey, and Eisner awards, the Guardian First Book Award, an American Book

Award, the Prize for the best album at the Angoulême Festival and Critic’s Prize, and Grand Prize of the

city of Angoulême.

I had the pleasure of

viewing this impressive retrospective in person this past summer. The show gave

a window into Ware’s prolific, multi-faceted work for which he has won great

international acclaim. The exhibition was for anyone interested in his work

including those highly versed in it as well as those beginning to discover it.

The overarching arrangement was

chronological with the following sections: issues of the Acme Novelty Library;

three groups that largely feature selected drawings and color enlargements for

each of Ware’s graphic novels; and Comics & Co., an area that presents examples

of the artist’s work for magazines, posters, and short animated films. Exhibit

texts were in French but included some portions in English in smaller type.

French editions of Jimmy Corrigan the Smartest Kid on Earth, Building

Stories, and Rusty Brown, attached to stands, were easily browsed

and helped anchor each group of items related to each graphic novel.

On entering the Bpi, it was

easy to find the exhibition. Just inside the entry were large cases containing numerous

issues of The Acme Novelty Library, the ongoing series that Ware began

in the 1990s. The differing sizes, formats, and stylistically-changing cover

designs hinted at the contents within and several examples were opened to

display some of the highly varied comics stories (unsigned and purporting to be

by multiple creators), cutouts with instructions for assembly, and articles

addressed to readers. Some issues presented versions or portions of comics that

eventually became parts of Ware’s graphic novels including Jimmy Corrigan

the Smartest Kid on Earth.

The section devoted to Jimmy

Corrigan (2001) included drawings and enlargements that primarily highlight

the feelings and musings of Corrigan, the middle-aged, highly introverted

protagonist and his eventual meeting with the father long absent from his life.

The work is semi-autobiographical in that Ware draws upon his own experience of

meeting his own absent father while he was working on his novel. In one drawing

Ware shares Jimmy imagining what his father looks like by depicting multiple

images of older men’s bald heads shown sequentially in a grid. In an online

tour, curators Misserey and Peeters commented that making such use of the page

at this time was highly innovative formally. They also mentioned Ware’s

interest in evoking nostalgia tinged with sadness and detailed rendering of such

architectural settings as the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair, for example. Such interest

continued into his work that followed.

The section on Building

Stories underscored the unconventional nature of this graphic novel that

consists of fourteen separate printed works cased in a box that tell stories

about people living in one building. An

exhibit case containing multiple notebooks relating to the graphic novel gave a

glimpse into Ware’s creative process. As noted in the exhibit brochure, the stories

of people in the building gradually build a portrait of one resident, a woman florist

and aspiring artist with one leg. One of the most striking original drawings in

this section featured a life-size rendering of the artist’s daughter based on

her actual size at the time he drew it. This presented formal challenges in

balancing the large form with smaller visual units, a challenge that he handled

with impressive skill in composing the double page spread. Misserey and Peeters

observed that the drawings and color enlargements in this section demonstrate that

Ware had moved beyond a semi-autobiographical milieu to create a world that

reflects increasing engagement with others.

Some of the most compelling

pieces in the section on Rusty Brown portray the character Joanne Cole,

a Black teacher at the school attended by Rusty. To this reader, she is also

one of the most interesting and sympathetic characters in the novel. The

drawings on view included key scenes in her professional and personal history:

we see her seeking to connect with her students, her strong engagement with

playing the banjo (an interest shared with Ware), her careful interactions with

white colleagues (much of which require repression and self-containment),

qualities so well captured in Ware’s depictions. His imagery conveys a

broadening of his relationships with others in the world. I agree with Misserey

and Peeters who pointed to a growing sense of empathy and compassion toward

others that is seen in this work.

Midway through the show, a

video of Ware being interviewed in his home and studio provided an engaging interlude.

A clip that showed him at work using his straight edges and fine tipped pens conveys

some of the intense focus required to achieve the precision, care, and thoughtful

deliberation so evident in his work.

The section Comics & Co.

presented examples of such additional work as a beautifully drawn cover for The

Ragtime Ephemeralist, covers for The New Yorker, architectural

drawings, and short video animations. Ware’s designs for The New Yorker,

in particular, stand out not only as visually arresting but also as full of

nuanced, thoughtful perspectives on the state of American society that reference

the impacts of heightened socio-political divisions, the pandemic, threats of

mass shootings at schools, and more. His architectural drawings also reminded

me of how he uses this well-honed skill in rendering Midwestern architecture in

Omaha and Chicago, in particular, to evoke a sense of place that contributes to

narrative atmosphere and immediacy in his graphic novels.

Further evidence of Ware’s

multi-faceted interests and talent could be seen in several cases that

displayed small wooden objects--figures and toys that he fashioned by hand. While

some of these playful objects portrayed characters in his comics, others in a

case near the end of the show were made for family events such as birthdays. Including

such objects underscored the importance of family as well as work in his life.

When interviewed in

conjunction with this exhibition, Ware agreed that he identifies as a “full

‘book artist.’” As he draws, writes, and designs his books, he tries to keep in

mind the ways in which a human being is like a book in that it has a spine, is

“bigger on the inside that the outside,” and can convey the truth about itself

(or not.) He also said that a book is “also the only art which pretty much

anyone can afford and own.” While the original drawings in the exhibition are

one-of-a-kind, Ware also says that they represent “simply one step” in his

creative process: “the finished, printed object is the art itself.” This emphasis

on the book made the Bpi seem the perfect venue for this artist’s superb retrospective.

No matter what aspect of Ware’s work you find most compelling or admirable or challenging,

this exhibition shed light on your understanding of his art, him as an artist,

and a human being.

....although we'll take donations as well. Paypal him at john.lent@temple.edu A Cry for Financi...