by Hélène Tison

Leela Corman is a painter, educator, and graphic novel

creator, working in the realm of diaspora Ashkenazi culture and

third-generation restorative work. Her books include Unterzakhn

(Schocken/Pantheon, 2012), which was nominated for the Eisner, the L.A.

Times Book Award, and Le Prix Artemisia, and won the ROMICS Prize for Best

Anglo-American Comic and the MoCCA Award of Excellence; the short comics

collections You Are Not A Guest (Field Mouse

Press, 2023) and We All Wish For Deadly Force (Retrofit/Big Planet,

2016).

Her graphic novel Victory

Parade, a story about WWII, women's wrestling, and the astral plane

over Buchenwald, will be published by Schocken/Pantheon in April 2024. Her

short comics have appeared in The Believer Magazine, Tablet Magazine,

Nautilus, and The Nib. She is a founding instructor at Sequential

Artists Workshop, and an instructor at Rhode Island School of Design. She is a

Yaddo Fellow, a MacDowell Fellow, and the recipient of the Xeric Grant, the

Sustainable Arts Foundation Grant, the Helix Fellowship, and the Koyama

Provides Grant.

Her contact information is:

http://www.leelacorman.com (currently down as of 12/30/2023)

Bluesky: @leelacorman.bsky.social

Instagram: @leelacorman

This videoconference interview with Leela Corman took

place on Nov. 28, 2023. It has been edited for clarity. All artwork is copyright by Leela Corman.

Portrait of the Artist

Hélène Tison: Thank

you so much for your books, and also for agreeing to this interview. So today

we'll talk about your new book Victory Parade [April 2024; reviewed

here: http://ijoca.blogspot.com/2023/12/the-look-of-ghost-with-ashes-in-her.html],

but maybe also about your other work, if that's ok with you. I was really happy

to see that you were able to republish some of the work from We All Wish For

Deadly Force, which you were a bit frustrated with I think.

Leela Corman: Yeah,

it didn't print well for a variety of reasons. So it was really important to me

to reprint at least my favorite work from that.

HT: The

first question I wanted to ask is about your art, because your work and your

style I think are rather unique and beautiful, very poetic, very painterly. And

it probably takes you a very long time to make, so can you tell me a little bit

about how you work, your technique, your tools, et cetera?

LC: It

does take a really long time to make a project like Victory Parade. I

will say it also took a long time to make Unterzakhn, which was just in

ink, in part because the writing aspect of my long form work is really

important. And I spend a lot of time, especially with the longer books, really…

First of all, I do a ton of research and that takes a lot of time and there are

a lot of stages to the research and there's a lot of stages to the note-taking

that goes along with that, before there's even anything written down, that

becomes the story.

|

| “Wilderness” in You Are Not A Guest, 71 |

Then it takes a long time to thumbnail the story,

which is where the actual writing of the story itself happens. The dialogue and

the action happens while I'm drawing. I don't write a script in advance because

I can't think without the pictures, the characters don't come to life, they

don't even exist until I start thumbnailing, sketching.

And then when I started painting my comics in

watercolor, it instantly made my work better and it completely changed my

career. It also meant that the work took a lot longer and in a lot of ways I

think that that was something I was searching for. I'm not sure I really knew I

was looking for that exactly, but I always had this feeling that my work wasn't

getting to the depth that I wanted it to, and I had been trained… Uh, well, if

you really want to go back, I thought I was going to be a painter, and then I

got kind of heartbroken by a very cruel teacher, my first painting instructor

actually who just wanted to make sure I didn't become a painter, basically. And

she almost succeeded; and I learned from her how not to teach, but it took me

20 years to come back to a place where I could pick up a paintbrush again. And

in the intervening years, I became an illustrator, which felt a bit like a

diminished path for me because it was not where my heart really lay as an

artist. But I had a lot of fun doing it. What it meant, and this brings it back

to your question, what it meant was that I had to train myself to work very

quickly. So I started working with line a lot and flat color, digital color -- the

line was always hand inked, but everything else was digital to try to get

things out quickly. You know when you're an illustrator, everything is very

fast turnaround and I developed a style that was sort of easy to do that in,

but I got really tired of it after a while and when I hit that turning point in

2015, when I started watercolor-painting my comics, that took me out of that

completely. The pages in Victory Parade are definitely the most labor-intensive

work that I've ever done.

HT: What

format do you originally work in? I imagine your page initially is bigger than

the book format, right?

LC: Yeah,

a little bit. I initially had wanted to print it at the size that the art was

painted, 11 by 14 inches; the printing is not that much smaller, only a couple

of inches. With Unterzakhn, the pages were gigantic, they were 19 by 24

inches, because I wanted to make something that felt like gesture drawing. With

Victory Parade, I was really working like a miniaturist, with a tiny

little brush. Now I'm starting to make large paintings again. There's one

behind me almost as tall as me; I’m not very tall, but I'm taller than a book. [laughs]

HT: What

tools do you use? Do you do everything manually, or do you use a light box, a

computer?

LC: You

know, I never used a light box. I'm not sure why I never tried it and maybe

it's just never really been necessary for me, but no, I do everything manually

until the scanning and production. The lettering is digital, but it's a font of

my own hand-lettering. I hand-lettered Unterzakhn and I will never do

that again. I'm just not good at lettering and I don't enjoy it, so it's nice

to have that part be digital, but everything else is by hand because that's how

I think.

HT: You

talked about switching to color after Unterzakhn which was in black and

white, was that because you had more time to devote to the to the art?

LC: No,

it was aesthetic. I've always loved working with watercolor, and I didn't like

doing it as an illustrator. It's funny, I have opposite points of view for

color with illustration and with comics. I will say also I no longer take

illustration commissions -- unless they're really special, like a musician that

I'm friends with wants me to do a poster for them or something. But when I was

still doing illustration, once in a while I would try to do it in watercolor

and I didn't enjoy that. It just didn't feel sharp to me.

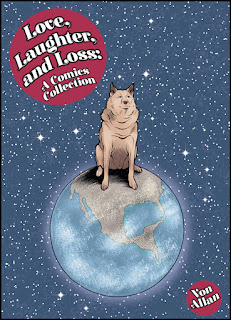

|

| You Are Not A Guest, cover © Leela Corman 2023 |

The opposite is true with comics. I can't stand

coloring comics digitally. It makes me crazy. It doesn't feel like art to me.

I'm not saying it's not art for other people, but for me I need to be working

with chaos, the controlled chaos of paint. So, I always really loved working

with watercolor, but I didn't do it for a long time between my adolescence and

adulthood, and for some reason I just put it aside. And then one day I just

experimentally started playing around with it in in a sequential way and it was

kind of a shock like -- what is this, what is happening here? And so I decided

to do a piece that was really like the turning point in my career, which was

the one about PTSD that I did for a science magazine called Nautilus. [“The

Wound That Never Heals” reprinted in You Are Not A Guest] I thought,

well, what would happen if I did that in watercolor? and it completely changed

my life.

I guess it's funny, I've never thought of this before,

but this is a really obvious comparison: The Wizard of Oz, where the

world goes from black and white to color [laughs]. And no, I don't have more

time; having said that, the last seven years or so I had a perfectly fine

amount of time. I have no time now, which is good because I'm done with the

book, I can take a break.

HT: In

your non-fiction, (You Are Not A Guest, We All Wish for Deadly Force)

there is a lot of accompanying text, a sort of narrative voice, contrary to

your fiction, Unterzakhn and Victory Parade, which are told

through images and dialogue exclusively. Why is that?

LC: Good

question. You know, it's not a thing I planned, but when I work in short

nonfiction, my voice is in there just by the nature of the piece. It's more

like a graphic essay, and when I'm working in fiction, I'm not interested in an

omniscient narrator. I want things to unfold -- I was going to say in a

cinematic way, but there's certainly plenty of cinema storytelling that has a

narrator in it. And now I'm racking my brain to think are there any films that

influenced me that have an omniscient narrator?

The reason I'm mentioning film is because film and

episodic storytelling is the closest thing to what I do and it's the kind of

storytelling I've learned the most from, that comes into my own work. I think

about film all the time. And when I think about the films and the filmmakers

that are the biggest influences on me, they mostly don't use omniscient

narrators. It's almost entirely dialogue- and image-driven and action-driven,

although there are some exceptions -- Wings of Desire, if you remember

that film, sometimes there's some narration and it’s a little bit oblique

because it's not really a person narrating it. It's this kind of exterior,

higher being observing. It's a poetic kind of narration. It's not like a noir

film, where the narration is somebody reminiscing about their life or

something. That would be an interesting experiment, to make fiction that has

that. What would happen if I did that?

HT: That

would make it very different; I was thinking, for instance of Fun Home

that is completely dialogic, with narrating voice and dialogue.

LC: Well,

that's a work of memoir, which lends itself to that in comics very well. Now

I'm trying to remember I don't have Maus right in front of me… That's a

testimony that's being illustrated, in a lot of places, the places where there

is the narration of the father's voice, but then there are places where they're

interacting, and that's entirely dialogue-driven. I find that very interesting

too.

But in terms of fiction, Jaime Hernandez sometimes

brings in an omniscient narrator. Well, it's not an omniscient narrator. It's a

character talking about their life. But he's Jaime Hernandez -- he's God, you

know. Whatever he does, it's like up there somewhere.

HT: Language

is obviously really important in your work. Can you talk a little bit about

that? Did you grow up in a surrounding that was multilingual for instance?

LC: I

did, I grew up in Manhattan in the 80s, and so my neighborhood was

multilingual. There were a lot of Spanish-speaking and Haitian Creole-speaking

people, and then my family spoke Yiddish and Polish and English. They almost

never spoke Polish. They would argue in Polish if they didn't want my mother or

my aunt to understand them. If they were trying to keep something really

between them, I never really understood Yiddish beyond the very basic -- like

endearments: how are you doing? What are you doing? I love you. Eat something.

Why aren't you eating? You know a lot of stuff about food, curses; but I grew

up around a lot of Yinglish, which is a really specific way of speaking English

with a Yiddish syntax and accent. The generations that are familiar with that

are probably my age and older. And I worry that that feeling, that that

particular slang is going to be lost, you know? It’s a voice.

It also is a voice that people are very familiar with,

at least in the United States, through comedy, and comedic writing like Mel

Brooks, a lot of his work is in Yinglish. But again, this is a generational

thing. And I feel like, if you didn't grow up with family members who talked

like that, you don't know what it is and I've seen people try to write it who

don't come from my particular ethnic background and they don't get it right. You

have to have grown up with it -- like this is just how we had to communicate in

my family with my grandparents who spoke five or six languages. But English was

the last one, and the one that they spoke the least fluently.

I love Yinglish. I love it so much. There’s a great,

old, old episode of the New Yorker fiction podcast, where Nathan

Englander reads the Isaac Bashevis Singer story Disguised. It's so great

and he talks a little bit, in the little interview with him either before or

after he reads the story, he talks about how he had gone to yeshiva as a kid

and how long it took him to stop using that kind of syntax in his own writing. And

I thought listening to that why? Why would you give it up? But I get it. You

know, like you're not going to write an academic paper in it, but… and vy not?

Vy you don’t? [laughs]

HT: Going

back to drawing, how important in your experience is the haptic or the sensual

nature of drawing and painting? In particular, when you're representing

characters, whether in fiction or in nonfiction, how important is the process

of spending time on drawing, redrawing, creating human figures, in your

practice?

|

| Victory Parade 29 |

LC: It's

the most important thing. It's absolutely the most important thing. I love that

you use the word haptic. I'm going to have to steal that and start using it

myself, because I almost feel like I have to defend the practice as a teacher,

trying to explain to students: Well, I'm not against you making comics

digitally. I think they're beautiful, but I want you to have a particular

physical sensory experience. I'm a figure drawer and figure painter; to me

figure drawing and working with the human body is endlessly compelling and

extremely important. So working with paint and texture and viscosity became

such an important part of constructing Victory Parade especially.

HT: I

was struck by Thi Bui who, in an interview about The Best We Could Do,

said that having to repeatedly draw her mother as a child actually reconciled

her with her mother, with whom she had sort of a distant relationship, and

having to draw her repeatedly was important emotionally for her.

LC: That's

amazing. That is really incredible. I love her book.

|

| Unterzakhn 10 |

HT: Yes,

it’s an amazing book. All right, completely different topic. The US has changed

a lot since Unterzakhn came out, in 2012. By the way, I’m not sure how

to pronounce it.

LC: Well,

you know, that word is not dialect. I think maybe someone's going to read this

interview and they're going to write me, and they're going to take me to task

for saying that, but I believe that word is academic Yiddish. The person who I

got it from I was a sort of Yiddish consultant on the book who was like a Yivo-trained

Yiddish speaker, and I think she grew up speaking in her family too, but she

also had some formal academic training in the United States, learning academic

Yiddish. My mother was like, what is this word? And I had this nightmare experience

at Miami Book Fair: this lady who looked just like one of my tantes, she had,

like the butterscotch-colored kind of big hair and the coral fingernails, and

she says: “I grew up speaking Yiddish and I've never heard this word Unterzakhn”,

and I was like, oh, it's academic. [laughs] Anyway, I don't put a vowel between

the K and the N, but you could say it in the way you want.

Comics and Politics

|

| Unterzakhn 11 |

HT: Ok,

thank you. So, the US has changed a lot since Unterzakhn came out, in

2012, and in that book you discussed, and illustrated, the vital need for

access to birth control, and I was wondering if it (or any of your other work)

has been banned anywhere.

LC: Well,

I think because no one's gay in that book, at least visibly, the neo-Nazi

cultural crusaders haven't found it yet. I do remember reading that it was on a

banned list in some prisons -- I guess they don't want incarcerated men having

abortions. Or maybe because there's boobs in it.

I was making a very dark joke last year that not

enough people in Congress have read my abortion book. But yes, things have

changed a lot, but at the same time, it's more like who gets to say, who gets

to be in control. The forces that are in control right now have always been

here. They're not new and we've always been a country that tends more towards

the fascistic.

HT: The

same thing is happening in Europe currently, it's pretty scary. Being French,

we've been under the threat of the Le Pen family for 30-40 years now.

LC: Incredible

to think of it right, this one family that looms over this one country's

politics. And when will that stop?

[…]

HT: I

didn't want to talk too much about current politics, but…

|

Victory Parade, cover © Leela Corman 2023 |

LC: But

I think it's not irrelevant to my work, and we need to look at fascism as a

force that rises and falls globally. It has characteristics specific to each

country that it shows up in, but maybe if we can look at it as a global force,

we can find solidarity against it globally. I don't know, and I'm just an

artist, you know? But Victory Parade -- I felt when I was at the

beginning of making it that it was my antifascist work. Like this is what I can

do right now. Now it feels like events have completely overtaken me.

[…]

HT: Reading

your work from the beginning, you seem to approach some of the very central and

very tough themes in your books with a certain reluctance. For instance, in an

interview, I think in 2008, you said that you didn't want to talk about WWII

and Poland, that you were wary of the topic. And in 2012, you said that you

didn't see yourself as a feminist; yet these two things are so central to your

work.

LC: Oh,

my God, no, I what the hell is wrong with me? I mean, of course I do. I think

also 2012 was the worst year of my life. And there are probably a lot of things

I said then, the context would have to be there. But I used to have a lot of

the same issues with the word “feminism” that I think a lot of women of my

generation had in the 90s and early 2000s. Second wave feminism had come to

feel restrictive, sometimes; we were tired of getting lectured, in ways that

felt puritanical, about sex and about porn and about eroticism and all these

things. There were some real hard doctrines around that stuff for some second wave

feminists that I encountered personally and in media, but god! there's no way I

could say that about myself.

HT: But

I wondered also if it had to do with something that's obvious in your fiction

and in your nonfiction: the problem with silence, not talking about tough

situations, history, etcetera. There’s an anecdote that you tell in your

nonfiction and your fiction, which is the metaphor of the carp that is

going to be put to death, but we don't talk about it. I thought maybe that was

sort of a clue -- there are certain topics that are so important and so central

and painful that perhaps in your family there was some reluctance to tackle them.

|

| You Are Not a Guest 66 |

LC: Well,

in 2008 I didn't feel like I could [talk about World War Two]. I had gone

through a period of being very obsessed with certain aspects of World War Two

and then needing a break. I wanted to do work that was not related to it. And

then when I had the idea for Victory Parade, it wasn't initially about

anything that happened in Europe. It was very New York focused. Then I realized

well, if I'm going to tell a story that takes place in the 1940s, of course it

has to engage with World War Two.

The initial idea was about women working in war

industries. That was the first image; I had to engage with it. And then in

2015, I started to see the turn towards fascism and the language about

immigrants coming to the United States being exactly the same language that was

used about us in the 1930s, exactly the same. All you have to do is take out

the words Jewish and put in the word Syrian or Iraqi. And there was this idea

in 2015 that ISIS infiltrators might sneak in among Syrian refugees in the US. It's

a stupid, racist construction, right? In the 1930s, there was this fear that

Nazis would infiltrate among the Jews. Like, really? Come on, that is not going

to happen.

But here I am meeting a bad faith argument with a good

faith concern. The people who are saying those things don't really believe that

either, it's propaganda, but it was very obvious to me in 2015 that we were

going in a really dark direction, and I felt like I was seeing and hearing this

stuff on the horizon, that a lot of people were not. And I'm not trying to give

myself credit for it, just like I have Jewish radar, you know? I was really

horrified by the inhumanity of it.

And then when I started working on Victory Parade

the following year, it was right after Donald Trump was elected. And everybody

was scrambling to understand what was happening. And some of us were sitting

there going, “We fucking told you. This is the obvious direction of

things.” There's even now this constant, irritating discourse in the US, where

people will ask themselves and you'll hear people in the media posing the

question, “is it time to use the fascism word?” My God, it's been time to say

that since at least 2015. And you know, if you want to look at the actual

history of the United States -- and I'm sorry, this is not relevant to my book

exactly -- but the entire history of the United States is a history of racial

fascism.

HT: But

I think it is relevant because in Victory Parade, I picked up certain

clues that you were also talking about America when you were talking about the

concentration camp, for instance.

LC: Absolutely.

HT: One

of the first images when Sam arrives at Buchenwald, you draw the camp and the victims,

and the word America appears, spoken by one of the prisoners, but it appears in

the middle of the panel. It's superimposed on the concentration camp. Also, I

thought that although you’re not talking about Hiroshima and Nagasaki, I sensed

it in there somewhere; and then at the end of the book, you have this quote by

Shōmei Tōmatsu, the Japanese photographer who's famous for having photographed the

aftermath of WWII and the bombs in Japan.

LC: Yeah,

that was his quote, after spending his career photographing hibakusha [atomic

bomb survivors]. It's funny that you mention that “America” quote. I'm really

glad that you had that double read on it. I didn’t intend it, but that’s my

favorite thing in art, and it’s something that I'm trying to figure out a

better pedagogical way to transmit to students, when the truth comes out

unintentionally or without being overdetermined and shaped consciously by the

artist.

So, what's happening in that set of panels where the

prisoners are saying “America, America” is actually what happened when allied

soldiers stepped through the barbed wire at Buchenwald, people started to say, “America,

American” and cheering for them. And other camps too, according to liberators'

testimonies. So that is just historical documentation, but the double reading

is really important, and accurate.

You asked about the carp and about not talking about

things -- I think most people who grow up in families where there has been some

kind of historical trauma, certainly Holocaust survivor families, but

definitely not limited to them, there's a lot of not talking. There's a lot of

silence and in American culture, especially among a certain class of white

people, there's so much not talking about things, and that's outside of

my own culture -- with Super American people, like my husband [laughs]. And on

a broader societal level, we still can't really talk about the indigenous

genocide our country is created on, or the hundreds of years of chattel slavery

and the barely better conditions now racially in this country. First of all,

just the brutality of slavery in this country, what that actually meant, you

can look at a history book and be upset that there was slavery, right? But when

you actually read about what the day-to-day life of enslaved people was, what

it was like to be captured, transported, what life was like on plantations,

what happened to people, to their children, to their bodies -- we don't talk

about that. And when people do try to talk about it, they're viciously censored

and punished for it. While there's this official kind of observance of, you

know, “things are better now,” and every year they trot out the Martin Luther

King quotes without really engaging with what his really serious work was, and what

is still happening now. There's this maddening silence around horror and

suffering in this country. Sometimes I feel like I live in a slaughterhouse

with a little window box full of sweet-smelling flowers in front of it.

[…]

Comics and Trauma

HT: Trauma

and its transmission from one generation to the next are also very central

themes in your fiction and nonfiction, and certain traumatic events create a

network that links your stories together. I was talking about the carp. I was

also struck by the scene in Victory Parade when the dead talk to Sam and

say: “we are teeth,” “we are bones,” “I'm with someone who knows you,” that

resonated with We All Wish For Deadly Force and with “Life Is An Ambush”

-- it creates a link with the story of your first daughter. Can you talk about

how you conceive of the relation between trauma and comics, and the usefulness

or the appropriateness of comics in narrating traumatic experiences.

LC: Well,

I think comics is an art form that lends itself to any kind of storytelling,

and one of my favorite things about it, and the thing that initially drew me to

it as a younger person, was that you can say and do anything in comics. And I

think you could make the argument that that's true of all art forms, right? It's

true of film. It's true of writing. But comics felt uniquely like an art form

that lent itself to the wildest explorations of any human experience, and I had

really great examples of this early on, especially Phoebe Gloeckner, Renee

French, Julie Doucet, artists like that, all of the RAW artists.

And maybe it's because comics is also such a global

art form and cultural product at this point. So many people in the world read

comics in some form -- comics come from all corners of the globe, it's an easy language

for people to learn visually. You just kind of grow up with it. It's

instinctual, so when you start putting heavier content, bigger content into it,

it naturally expands to include it, if that makes sense.

In terms of its use as a container for trauma

storytelling, I think it's really useful for that, in part because there's so

much malleability between text and image. Also, I have to say this connects to

your earlier question about the carp and about not talking about things -- I

hate evasiveness, it makes me so angry; I want to talk about things. This is a

maladaptive trait of mine, to want to talk about everything, and of course I

have my limits on that. There's definitely things I shut down about and don't

want to talk about. That's fine too; but pretending that there's not a carp

with a knife through it in a pool of blood on the counter, metaphorically

speaking, is something I really loathe. It feels like gaslighting to me. But to

be a little bit more gentle and compassionate, in families that have been

through the Holocaust, I can only speak for my own culture here, I won't speak

for other historical traumas, but I want to get to that in a second. In my

family, there were good reasons why people did not want to talk about what had

happened to them. It was too painful and the gulf of trying to reach someone

like me, for my grandparents, across the barriers of language and culture and

experience, to tell me, a privileged kid in New York City in the 80s and 90s, about

living in a hole in the ground in the forest. There's no way they could tell

me. Even trying to say the first thing about it is exhausting, so I understand,

I understand.

And in my grandmother's case, when she told me one

really terrible thing, she started having what I now recognize as the trauma

reaction, and I backed away immediately. I didn't want to make an old woman

have that kind of reaction, and I was afraid she was going to have a heart

attack. She was shaking, she was telling me about witnessing the liquidation of

her entire ghetto, from a hiding place. She was hiding in the attic of the

synagogue or a barn, I can't remember which, and they shot 950 people, basically

under her nose, and many of them were her family. So I never asked her to tell

me again. Consequently, a lot of stories get lost.

In terms of the links between other historical

experiences that you mentioned in this book, if you don't mind me going back to

that, that's really important. I think that there are two major ways that I see

descendants of the Holocaust, second and third generation, how we carry it in

the world, there are some people who respond to it in a way that is insular. This

is about us and only us, and we have to take land, and narrative and make it

only our own. No one else has ever experienced anything like this. Then there's

another group of people who say, this is a genocide connected to other

genocides. All atrocities are connected, and we find solidarity with each other

because our own people have been through something so terrible. I'm putting

this in terms that are so simplistic, I'm sorry. But for obvious political

reasons, I'm thinking about this a lot right now because I'm feeling like the

lessons of the Holocaust are being profaned every day in my name to justify the

murder of thousands of innocent people right now. So, I obviously count myself

in the second group. To me, it's really important to connect with and have

solidarity with everybody else on the planet in this huge mass grave of human

suffering that is this planet.

HT: And

as you said, it's important that the second and third generations talk about

these things because so much of the time, the first generation couldn't. In

France, a lot of people who had experienced arrests, the camps, were told not

to discuss it, also because the French police were so involved. Most of the

arrests were made by the French, not by the Germans. So the French did not want

to hear about it. And now most of the witnesses are dead, or very old. So the

next generations need to pick up those stories and tell them.

LC: Yes,

but everyone suffered also in France under occupation. And Poland gets accused

of collaborating with the Nazis a lot, but no one ever talks about the Western

European countries that collaborated really enthusiastically with them. I will

defend Poland here -- I know there was plenty of anti-Semitism to go around

there, and everywhere else. But Poland didn't even have a government during

World War Two, the government was a German Nazi government. And there are

countries that don't have that excuse. They were really happy to collaborate.

I have to say that the second generation here -- my

own family being a really good example of this -- usually can't talk about it

either, or when they do, it's really different. I mean, for one thing, that's

how I think a lot of hard-right Zionism became institutionalized in American

Jewish organizations. But my mother, for example, her generation, they really

have a lot of shame and their own trauma about it. It's very traumatizing to be

that generation too.

|

You Are Not a Guest 5

|

So I categorize my work very firmly in third

generation descendant work and there are a lot of other people like me making

work in all kinds of mediums and I've been finding them lately. It's really

nice to connect with them. But also, the people that I am associated with in

Poland are also doing third generation work; and this is work that the previous

generations really couldn't do because they were suffering the Soviet

occupation and its aftermath, they were just trying to survive in the Communist

era. And then as Poland became a capitalist country, that's a whole other part

of the story.

It falls to people my generation and younger to start

dealing with it, and also there's so much shame and so much trauma around

everything that happened during the Second World War and afterwards in Poland. I

don't want to speak out of turn, I'm not an expert, but just from my own

experience there and talking to people, people really suffered horribly.

[…]

Comics and History

HT: Going

back to Victory Parade, you said that you thought of the story of women

working in the war industry and then you moved on to Europe and to the

concentration camp. So how did that switch occur in your mind, and how do you

think the two topics inform one another?

LC: Well,

it's interesting when I think about the mechanics of writing this story -- I don't

remember the moment when I realized I could do both of those things in the same

book. But I've always been obsessed with concentration camp liberation stories.

I went through this period where I read them constantly, and I returned to that

when I started working on Victory Parade. And it just made sense that if

there is a woman who is working in the Brooklyn Navy Yard making warships, that

her husband would be serving overseas. And there are so many accounts of

American Jewish soldiers being part of the battalions that liberated

concentration camps and what they experienced. So there was already a lot of

material there for me to draw on. Lots of stories of people speaking Yiddish to

the prisoners; a completely different level of understanding what had happened.

Because we receive these stories about concentration camps, about World War Two,

kind of packaged. There are a lot of things that we already know, and it means

we don't always question “what are the things we don't know, what's not in the

package, where are the complications?”

This is really important to me as a storyteller in

general -- there are whole other layers to all of these stories, it's a really

vast topic. Imagine coming across one of those camps at the time, you don't

have the package -- you don't know what happened, it's totally incomprehensible,

you can't get your mind around what you're seeing. I was trying to put myself

in the mind of a person who had no idea what they were stumbling on, which is

one reason, and I'm sorry this might feel like a digression. Because now I'm

talking about the book itself, but one reason why I didn't feel the need to

show the gate of the camp, for example, is because I was trying to be a bit

nonspecific about it. It's very clearly Buchenwald, if you know the imagery of

that camp. But if you don't, it could be almost any concentration camp.

I'm frustrated with the tidying of the story of the

Holocaust and I want to stay very complicated and messy. It's not pretty, and

it's not redemptive, and people, at least in the US, keep trying to make it

those things. I don't know if that’s the case in France or anywhere else in

Europe.

HT: Yes,

but I was thinking about what you were saying -- in the early 40s, if you

wanted to know what was happening, you could. There were reports, including in

the US. But I guess a lot of the population did not know; was there a lot of

censorship, were people just too busy living day to day, and perhaps trying to not

know what was happening… France is a good example because we collaborated, but

we also resisted -- resistance is a great story to tell. Collaboration -- not

so good.

LC: You

know, it's funny the first time I went to France, one of the people I was there

with, a French comics person said: “everyone, every older person here is going

to tell you they were in the resistance. It's bullshit.” Which I feel is

probably a really incendiary thing to say, and I don't think it's entirely true

either: there was a lot of collaboration and a lot of resistance everywhere.

HT: And

a lot of in between. For instance, some of the German artists you mention in Victory

Parade (such as Oscar Schlemmer and other Bauhaus people, or what you say

in “Blood Road” about Franz Erlich) had an ambiguous relationship to the Nazi

regime, probably like most people who lived under this regime. Even if you

disagree with it, you're also thinking of your own survival, which I can

understand -- if I put myself in their place, would I have been up in arms

immediately? I thought of that also when I saw your quote on the SAW [Sequential

Artists Workshop] website, where you say you’re interested in breaking down, in

destroying the neat narrative of history.

LC: Schlemmer,

I actually don't remember what his story was. I think most of them probably…

you know, we have the benefit of hindsight -- they didn't entirely know. When

you read about Otto Dix, you read that he went into internal exile, which I

think sounds like what a lot of us are doing in the US -- in some way you could

say that about us. George Grosz, left, and he writes, in his journal A

Little Yes and a Big No, about leaving Germany when he knew he had to

leave. It's a really interesting passage, but my feeling during the Trump years

was, we're all good Germans now.

So I think I understand because we know -- we knew

that there were camps on the US/Mexico border full of asylum seekers, with

separated families, people who were being left without shower or blankets in

ice-cold cells, children separated from their families for indefinite periods

of time and sometimes lost! Knowing what's happening in your own borders, right?

Let's bring it even closer to home. I keep saying we live in a racial fascism

here, that's been ongoing for hundreds of years. We're all just living our

lives in this kind of in-between knowing that these terrible things are being

done and that some of us are living on the safer end of those terrible things. It's

hard to make binary judgments when you know that you're doing the same thing. I

think then it requires… I don't know what it requires, but it's something other

than how we've been thinking about these things.

Then there are people who I think were ideological

Nazis. Unfortunately, I think Christian Schad joined the party and I love his

work. I really can't engage with it anymore or show it to my students because

I'm not going to excuse that in a person.

HT: In

a sort of related question, your main character, Rose, and her occupation, of

course, recalls Rosie the Riveter.

LC: That

was an accident. [laughs]

HT: It

was an accident? That's very funny. So, I thought that was interesting because

it also put me in mind of Unterzakhn and your reclaiming a lot of

American history as not just WASP, and as also belonging to minorities. The USA

you depict in Victory Parade and in Unterzakhn contribute to a

sort of rewriting of the country's past and origins, to include the very people

who have always made up the country and yet are still perceived as on the lower

end of the hierarchy. So you’re not just showing multiculturalism, but

reclaiming American history as multicultural.

LC: I

love that and I'm honored that you see my work that way because I would not

have put it in those terms. But it's absolutely something that I love to hear,

and I do feel strongly about. I think it came naturally because I'm from New

York, I write about New York, and New York is different from the rest of the

country in a lot of ways, it’s a resolutely multicultural place. It's not

exempt from any of the racial hierarchy or class power structures of the country,

if anything, it reproduces them in an amplified way in some cases, but when I

go to other parts of the country, I can feel the cultural difference. And also,

being a Jewish woman, an Ashkenazi woman, it's a really particular way of

behaving and looking at the world, and how we're socialized is not like a lot

of other American women are socialized. I don't want to make overly broad

generalizations, but it’s something I struggle with a lot. So maybe it comes

through in my work, obliquely: living in a Christian hegemony as a minority, I’ve

resented it all my life since I was a small child during the Reagan

administration. He was the Christian right’s president. He was the guy who brought

them into power. So my entire life, I've basically lived under their cultural

control and it is actually quite relevant to my work in that I'm pushing

against it so much -- in Unterzakhn very explicitly and in Victory Parade,

talking about something else, centering someone else.

Comics and Bodies

|

| Victory Parade 22 |

HT: Another

important topic in in Victory Parade is sexual harassment, which makes

the character of Ruth furious, and she's encouraged in her fury by this sort of

other-worldly being. I wondered if that reflected your own anger. Also, about the

scene where she beats up the guy on the street who's been following and

harassing her and her friend, I thought there was a sort of superhero dimension

to it: we have her origin story, her superpower, and then her very impassive

attitude after she's meted out justice.

LC: Stroking

the man’s teeth on the handkerchief, enjoying her prize? I think that passage

is pure wish-fulfillment for me and a lot of other people. Who among us has not

wanted to do that? I set out wanting to talk about sexual harassment a lot more

than I actually accomplished. It's in there and it's pretty constant, but it's

barely scratching the surface. I'm going to have to keep engaging with it in my

future work. But it was such a constant in my life from the time I was twelve

years old, you know, I couldn't leave my apartment building without

experiencing groping and horrible comments. No one prepared me for that as a

kid, and no one supported me or gave me any kind of help when it was happening,

including my mother.

[…]

HT: In

Victory Parade, more than in your other work I think, you de-idealize

the bodies. They're not sexy, and even Ruth, who is young and strong ends up

dying at a very early age, so her body lets her down as well. Can you talk a

little bit about that and maybe also come back to Oscar Schlemmer, whom you

reference a lot and whose approach to bodies is so at odds with yours.

LC: Yes,

it is. I think the primary Neue Sachlichkeit [New Objectivity] artist that gets

referenced in Victory Parade is Otto Dix -- talk about de-idealizing the

body! No one makes a body less sexy than him, right? So Dix and his compatriots,

and maybe also H.R. Giger, there is absolutely nothing sexy about his work,

even when he's drawing a giant penis, it's like the ugliest thing you've ever

seen. I love Giger, anyway, so, with respect.

But Schlemmer, the way that he depicts bodies, they're

not flesh, the way he paints people, they look like pegs and carvings of wood

or they're these incredible theatrical costumes where the body is the axis

around which the costumes revolve. But the costumes aren't made to enhance the

body, they're coming off of the body in these really interesting ways. I love

his theatrical costumes, but if you watch any of the recreated footage of the Triadic

Ballet, it's not a loose flowing dance; the dancers aren't allowed to actually

use their limbs in ways that ballet dancers tend to. They're wearing these

really hard costumes that dictate the movement.

I like that you said de-idealize the body -- maybe

it's a side effect of living in a body that's getting older and hurting a lot

more. [laughs] No, but it didn't start out that way, I started this book six

years ago, so I didn't hurt as badly as I do now, but I find all kinds of

bodies really interesting and I guess I'm trying to get away from constantly

drawing conventionally beautiful people because it's really easy and fun to do

that.

HT: And

it's still dominant in comics; non idealized, realistic bodies in comics are

not that common.

LC: I

guess it depends what comics you read. I'm thinking about the Hernandez

brothers, constantly drawing very realistic bodies, and drawing them as bodies

that have every bit of a sex life and a sensual life as an idealized young

body. Chelo or Luba in Gilbert Hernandez’s stories have round stomachs and

stretch marks from childbirth, women have lovers and they are moms -- they're

fully fleshed out people. No pun intended.

HT: I

was thinking of mainstream comics, not so much independent comics such as yours.

LC: I

don't really read mainstream comics; and the artists that informed me tend to

be painters more than cartoonists. A couple of years ago I met this amazing

painter named Clarity Haynes at a residency and I've been really fascinated

with her paintings ever since. At the time, she was working on these monumental

torso portraits of people, and they were amazing. There would be aged bodies,

or bodies that had had top surgery, or bodies that had had heart surgery,

wearing a beautiful belt and necklace, or beautiful tattoo and scars, just so

lovingly painted and huge -- monumental. And I thought about those paintings a

lot. I'm not saying they're an influence on my work, just that I think there

are other ways to love and appreciate bodies, that are not mainstream comics or

fashion photography.

I had this experience last year: I went to the

Brooklyn Museum and there were two different exhibitions running at the same

time. There was a retrospective of Thierry Mugler, the couturier, it’s

beautiful work, right? But right before I saw that, I went to the exhibition of

the photographer Jimmy De Sana. It really blew my mind, it was really sexy and

really central in these ways that were, like, gritty, very queer. Also he took

a lot of photos of No Wave bands, which is a music and art scene that I'm

really fascinated by and I love a lot of that music. But also these really

beautifully lit, beautifully posed figurative photos that were so strange and

so… They felt like they were really about what sex actually is. It's body

fluids and flesh and smells and sounds and colors.

And then I went upstairs to this very idealized, you

know, everybody's super skinny. And like, it's about sex, but it's not really. It

gestures at the fact that you're supposed to find this sexy, but really

everything is very hard and regimented and skinny and there's no access to the

body in any kind of meaningful way. I wrote a much more articulate response when

I initially saw it, pairing the two.

|

| Victory Parade 148 |

HT: On

another topic -- Victory Parade is full of ghosts, or the undead. Is it

mainly narrative and/ or aesthetic? Does it have anything to do with your own

beliefs?

LC: It

was really important to me in this book to situate a lot of the action in the

world of the dead and the place where the worlds of the dead and the worlds of

the living intersect. I was thinking a lot about what happens in a place where

a mass death has occurred. It seems to me like the air would be disturbed by

the deceased, that they would be very present.

I've become a much more skeptical person than I've

ever been in my life in the last few years, and so I I'm much less interested

in the supernatural than I used to be. I was more interested in that when I was

working on the book; the dream state and the death state were things that I was

really interested in exploring. And I tend to feel very haunted, especially

back then when I started working on it. It’s things I think about and respond

to a lot.

HT: It's

just a detail, but in the scene where Sam finds the women’s hair in the

concentration camp, you draw him standing in front of the hair and dozens of

pink ghosts behind him, and I thought that the one that's just above him, who

is not as emaciated and who looks much angrier than the others, that it looked

like a much more specific ghost; I thought maybe it was even yourself that you

were putting in that drawing.

LC: I

was just looking at that drawing this morning actually. No, it's not me, but in

a sense everyone in the comic is the cartoonist, or everyone in a novel is the

novelist. A lot of the time, from the very beginning, when I was drawing the

scenes with ghosts, I was thinking about putting faces to names, putting faces

and names on the dead. Somewhere in there I realized this book is in dialogue

with Maus in that way because in Maus, Spiegelman made a very

deliberate choice not to do that. And I think it was a really wise choice for

the time and the audience, making everybody an animal. And thus not

expressionistic in any way, even though his line quality is very

expressionistic, capital E expressionistic. It's like a pill pocket, you know,

when you have to give medicine to a dog or a cat and there's a little treat

that has a hole in it and you stick the medicine in there and you shove it in

their mouths. It's like that: get the story past people's disgust or fear

reaction.

In my case, I felt like I wanted to do something else.

These are individual human beings with faces, and there's another running theme

in Victory Parade that was really important to me, which was to show

lots of different kinds of massed bodies. You'll notice there's a couple of

scenes that are recreations of Busby Berkeley numbers also. I love Busby

Berkeley, I'm totally fascinated by those films, but I was thinking about the

connections between masses of dancers and masses of soldiers. And then there's

these mass graves full of full of bodies. Or prisoners in the concentration

camps, full of the barely alive. All of these kind of massive collections of

people. I was thinking about that a lot, and I was also thinking, yeah, these

women are pissed. They're really mad. Those pink ghosts above him? They're fucking

furious.

HT: Talking

about names, there is also a scene where Sam is visited by ghosts who give him

their names, are these specific or are they random?

LC: They're

random -- although there's names of friends and writers I like; but they're

mixed up, they're randomized, the first and last names.

HT: You

were talking about Busby Berkeley -- can you talk about the final gruesome

ballet in the book?

LC: It's

probably the most transgressive thing I've ever drawn in my life. And I use the

word transgressive really carefully because I came of age as an artist in a

time when that was of great value, to make things that were transgressive and

everyone was trying to do that, and I think very few people actually made

anything that was that.

OK, so I take notes on index cards when I'm working

and it'll be like one idea, one beat, one statement per card, and then the

result of that is that I'll have a stack of index cards going back a few years,

sometimes with projects, and then sometimes I'll forget ideas that I had. This

is why I take them down on cards. So I found a card I had forgotten about where

I wrote “Busby Berkeley death scene.” And this is two years later and I was

like, “thank you past me!” I was very grateful to 2017 Leela because this was

such a good idea and it just made sense to me that this would be the scene you

would find at the end.

HT: So

bringing together these differently “massed bodies” as you were saying. It also

made me think of the film by Roberto Benigni Life is beautiful. When I

first saw this comedy about the concentration camps, I was really uncomfortable,

I didn't know how to react; but I think it was brave. And I thought this was

also not just transgressive, but an act of bravery on your part because you're taking

a big risk, bringing those two worlds together to say something about those

ghosts that you're bringing to life, and about your vision.

[…]

LC: There's

another Busby Berkeley movie that shows up in the beginning and at the end, The

Gang’s All Here, which he made during World War Two. So maybe I'm taking a

risk, but you could make the argument that at the same time that all of these

people were suffering and dying, starving, people in the United States were

going to see The Gang’s All Here, going to the movies and seeing these

massed bodies dancing. So it feels like there's a connection there. I was

thinking a lot about the experience of being here in the United States while

all of this stuff is happening there in Europe, especially if your family came

from there and you still have connections there, this is the thing you read

about all the time. There were Jews in New York who knew that their families

were being slaughtered, and the guilt and the pain that they were carrying, and

the helplessness of knowing that this is happening. I think this is replicated

across time and all over the world in the refugee and asylum-seeking

experiences, once somebody gets out, they're always thinking about who's left

behind.

But I was thinking a lot in this book about how people

process collective trauma, and I think that that also comes back to the massed

bodies. There's a lot of stuff in this book about the collective and the

individual. So much of what's going on with Rose is the processing of how an

individual carries a group trauma, and she's not the only one.

To come back to that final scene, there's humor in it

too, and I think maybe that's where some of the risk lies. I'm interested in

your mentioning Life is Beautiful, I love that movie. I haven't seen it

since it came out, so I wonder how I'd feel about it now, but I remember in the

US people were so angry at that movie. I think actually this is something that

was in the DNA of the book, this image of Roberto Benigni holding his child,

you know, where he starts walking with his kid on his shoulder and then he

comes across a pile of bodies, a giant mountain of corpses, and he starts

walking backwards. He doesn't turn around because he doesn't want his kid to

see it. And he doesn't survive, you know, at the end Nicoletta Braschi's

character, the mother, is reunited with her child, but the father is gone, and

that scene almost broke me, because so many parents were not reunited

with their children.

HT: All

right, I have to let you go back to your real life, so two quick questions

about Victory Parade: how did you become interested in wrestling; and

why did you decide to recycle Meyer Birnbaum, a character from Unterzakhn.

LC: First

question: in 2015, John Darnielle from the band The Mountain Goats asked me to

illustrate his wrestling-themed album, “Beat the Champ” and I was really

flattered that he asked me instead of somebody who's known for drawing wrestlers.

I had never drawn a wrestler at that point -- he could have called Jaime

Hernandez who draws the best women wrestlers, but he called me. I had a really

good time and I realized I love drawing, sweaty, muscular bodies in motion. And

I loved -- talk about drawing de-idealized bodies -- the theme of that album

wasn't just wrestling, it was early 80s local territory wrestling, which is

before wrestling became this shiny, glitzy thing. If you watch video footage

from that era, they don't look like glamorous muscle men, they're grittier.

I think there's also a connection, in the United

States anyway, between immigrant grandmothers and wrestling -- my best friend’s

Irish great-grandmother was obsessed with wrestling, my Yiddish grandmother

loved wrestling. She loved Hulk Hogan, I think because his character was the

anti-Communist Cold War wrestler. There's a lot of funny stories about people

going to wrestling matches with their grandmas and stuff like that.

I also have a background in martial arts and dance, so

I really liked drawing the physicality -- and it made sense that this character

[Ruth] would be a wrestler and that that would be her kind of trauma coping

mechanism and that it would be the thing that kills her.

Now the thing about Meyer Birnbaum is he wrote himself

into Unterzakhn -- I don't feel like I created him. I feel like he

showed up one day, just started talking. So it just made sense that he would

come back and be a wrestling promoter. But I will say it was a little more

conscious in this case, I'm paying tribute to a Gilbert Hernandez character

with him -- he's sort of the Gorgo of my book. He may even show up in the third

book -- this is part of a trilogy, so he might even show up again, and maybe even

somehow Meyer Birnbaum never dies. [laughs]

HT: Well

now I have to ask you about the trilogy…

LC: Ok,

so halfway through working on Victory Parade, I was in a café in Berlin,

sketching, and I was just looking around and I was thinking about being a child

during the late Cold War and all of the terror, you know, being absolutely sure

we're going to die in a nuclear holocaust because the leaders of the US and the

Soviet Union were selfish and stupid -- and then how shocking it was when the

Berlin Wall came down. And I was just trying to question -- what was it like to

grow up on the other side of that wall, and all of this stuff… And then I

thought ohh shit, this has to be a book, doesn't it? So I started thinking

about my own childhood in the 80s in New York and thinking about all the things

that were cool about it, too. And I was like, God dammit, I just had a book

idea, didn't I.

So the third book in the trilogy is set partially in

the 1980s in Manhattan and partially in the forests of Poland during the 1940s,

and the way that I have been conceiving this book lately as I've worked through

the ideas more is that I want it to be kind of a tribute to the Yiddish women that

raised me, the war generation. Who are almost entirely gone now, but I've been

painting and drawing them and thinking about them and… but it's about a lot of

other things. I'm also not ready to work on another book yet. My arm is tired,

it needs a break.

HT: So

there will be a trilogy, but I shouldn’t hold my breath, right?

LC: No,

it'll come. Yeah, my New York trilogy. [laughs]

HT: You

need to make one too! Ok, now just two or three questions about You Are Not

A Guest. I have a silly question, but it's inspired by the title of the

story, “The Fuck You Forest.” I thought that this was both painful reminiscing and

also sort of distancing, perhaps mocking yourself for the recurrent metaphor of

the forest as a place of trauma and refuge. Does this also have something to do

with the fact that Buchenwald means the beech forest?

LC: No,

no. “The Fuck You Forest” was made long before the comic about Poland, where I

said that thing about trauma and refuge. No, I'm not mocking myself at all. That

comic is the only comic I have ever in my adult professional life as a

cartoonist, improvised. I improvised an entire book when I was in college. My

senior illustration project was a comic that I totally made up as I went along,

but I hadn't done that since I was in school and I did that with “The Fuck You

Forest.” I'm not mocking myself at all, I was just in the rage part of grief.

HT: Mocking

was the wrong word, I’m sorry, but I thought distancing perhaps, because

there's a lot of images of trees, forests, mountains, rivers, a lot of nature

in your stories, and I thought perhaps, the forest as refuge turned out to not

work.

LC: I

think I was looking for solace in nature imagery, a place to hide. You know

when someone dies in a hospital, it's the least natural place in the world,

surrounded by the machines, and plastic, and chemicals.

HT: So

it's sort of an echo to the story “Wilderness” perhaps?

LC: Yeah.

And also well, “Wilderness” was so much about feeling like… that was done at an

inflection point in my life. A friend of mine had just committed suicide right

before I did that piece, and this was the friend who had taken us in after my

first daughter died also. So I was feeling a lot of just really feral emotions.

And I think also grief makes you feel like you live outside, it puts you

outside of society for a while, and I think that piece is about that a lot.

HT: OK,

I have a question which is maybe anecdotal, about “Life is an Ambush.” The end

of it felt like two worlds colliding almost. There's a beautiful, painful and

very personal story that I as a reader experienced in solitude but that also

created a sense of intimacy. And then on the last page you have this image of a

snake, and you address your readers about their potential online comments about

their birth beliefs. Have you had a lot of negative reactions to your stories

online? […]

LC: No,

it's because -- I did that story in 2016 and it was impossible to talk about whatever

your own birth experience was without a lot of other people piling on and

giving their opinions about it. And there was so much ideology and positioning

around it; and I used to have a lot of misinformed beliefs too, before I

had kids, about how you should give birth and what's good and what's bad. And I

had my mind completely changed by the experience. But also that was done in a

time when I was still grieving pretty hard and very angry. There was a lot of anger

in that piece.

HT: Alright,

concluding questions, for real this time. How have your books been received in

general? What kind of feedback do you get?

LC: Mostly

really good. I'll see what happens with Victory Parade. I'm feeling a

little strange about Victory Parade right now because it feels like, what

am I doing telling a story about the Holocaust? It made sense a few years ago

and now it feels like… I don't know, those thoughts are kind of unformed and

hard to articulate... And I haven't seen a lot of feedback yet to You Are Not

A Guest, so I'm not sure. It's been a while since I've put out a book. Yeah,

but mostly good.

HT: Do

you think that it's still harder today to be a female than a male cartoonist,

or has the cartooning world evolved enough that there isn't much difference now

in terms of publishing, readership, reception, etc.

LC: Well,

I think that there is probably some data science answers to that that I can't

give, that would really answer very clearly how much money people are being

paid, percentages of male to female, or male and everybody else in publishing.

I would say I think my career is going pretty well. But I think a woman who

works in the mainstream comics industry might have a really different answer,

or a woman in manga. I don't know what they would say. I am a little frustrated

that a lot of the same kind of old white men are still in power in some

publishing houses specifically. It just feels like it's never going to end. It's

been women who've really helped my career along, and I think that white men

still have unfair advantages everywhere, so publishing is probably no

exception.

But having said that, I think the problem and the

solution are related. The table keeps getting bigger; there are more voices in

comics now. So my feeling is: bring more chairs, right? This is happening in

some places like the Small Press Expo here in the United States. I had a twenty-year

gap between times that I attended: I stopped going in 2002, and I went again in

2022 and they were totally different because they had made a very conscientious

effort to make it a much more queer, female and nonwhite friendly space, I

think. And also, there's just more people making comics, there are more

education programs for comics, there's more opportunities to study it, and

consequently the art form is so much better because there are more people

making them and they're more diverse. Also, there's more examples of comics

from other countries in the US now; not enough stuff gets translated, but maybe

more than used to.

Anyway, I think you'd get a really different and maybe

more clear answer from someone working in the more traditionally male-dominated

areas of comics. I mean, women have always been an important part of every

sector of comics, but especially in art comics, we've really always been here.

HT: Do

you still belly dance?

LC: No,

I quit in 2017, quite happily.

HT: Ok,

well thank you so much, you've been amazing and very generous with your time

and your answers, it's been a pleasure talking to you.

LC: Likewise.

It was a pleasure for me too.

by David Beard, University of

Minnesota Duluth

by David Beard, University of

Minnesota Duluth