Articles from and news about the premier and longest-running academic journal devoted to all aspects of cartooning and comics -- the International Journal of Comic Art (ISSN 1531-6793) published and edited by John Lent.

Monday, January 31, 2022

IJOCA delays due to COVID-19 international postage restrictions

Wednesday, January 26, 2022

International Journal of Comic Art Index, Volumes 1-10 (1999-2008) online now

International Journal of Comic Art Index, Volumes 1-10 (1999-2008)

Tuesday, January 25, 2022

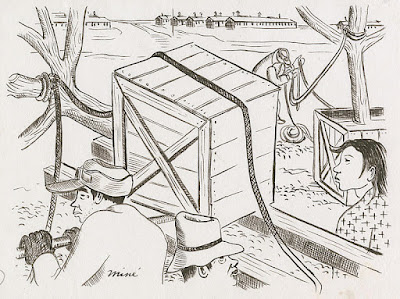

Good Humor, Bitter Irony: Reviewing “Miné Okubo’s Masterpiece” exhibit at JANM

reviewed by Tony Wei Ling

The museum’s path is a loop, and so a visit to JANM’s Citizen 13660 exhibit either begins or ends with a view into the same shambly wooden structure: an original barracks removed and rebuilt from the Heart Mountain concentration camp. Part of JANM’s ongoing exhibit on Japanese American history, Common Ground, this building-inside-a-building bookends the celebration of “Miné Okubo’s Masterpiece.” Visitors first travel through Common Ground’s rooms, which span the earliest waves of immigration through to WWII incarceration and its aftermaths; the final room, situated just before the entrance to the Okubo exhibit, covers the 1970s/80s political struggle for redress that followed internment. Along with the architectural bookend of the barracks, this history of the Redress Movement physically frames the museum’s 75th anniversary exhibit of Citizen 13660.

The JANM exhibit is structured into a narrative of the book’s production, displaying the variety of materials (varied camp sketches, original Citizen 13660 drawings, and page mockups combining drawing, typed caption, and marginal edits) in a compositional/editorial process of negotiated meaning. Miné Okubo’s iconic 1946 book pairs observational cartoons with terse first-person captions and follows Okubo through multiple relocations and incarcerations between 1939 and 1944: Berne to Berkeley, Tanforan to Topaz. By laying out the Citizen 13660 exhibit, room by room, into stages of drafting, design, and correction, the exhibit opens up for interrogation the multiple actors and influences that brought it into publication.

| ||

| Mine sleeping on a cot in her barrack |

Such an interrogation is important because Citizen 13660’s rendering of camp life’s “humor and pathos” has often been preemptively read as a political act in itself, one that critiques the events it charts and anticipates the organized call for reparations. No doubt much of this reputation comes from the book’s use as testimony in the 1980s, during which Okubo submitted her book to the Congressional Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians as evidence of government wrongdoing. However, scholars like Christine Hong warn against subsuming the book within this “retroactive interpretive lens,” since doing so “arguably obscures more than it illuminates Okubo’s legacy as a wartime artist.” Indeed, as Hong reminds us, Citizen 13660 could only have been published immediately following the war (and during the cross-country dispersal of former incarcerees) with the support of the WRA officials who ran the camps, some of whom endorsed the book. The book became, perversely, “an affirmation of the democratic potential of the American concentration camp,” Hong writes. This affirmation required fitting Okubo into the exemplar of an “entirely American” Nisei character (to quote Pearl Buck), such that reviews of her book sounded almost identical to the artist’s truly wild character references, such as the one from her teacher Glenn Wessels describing her as “un-Japanese in sympathies and in manner of thought.”

Citizen 13660’s legacy has continued to work through this exemplar form, making Okubo into an ethnic representative whose witnessing and recording of the camps always already testifies to one political end or another: either a distinctly American story that mines the everyday adjustments and discomforts of camp life for common ground with white readers, or a sharply critical, irony-laden statement of racial protest. Debates about how best to interpret “Miné Okubo’s Masterpiece” as a politically potent (though not obvious) artistic work are not about pinning down the precise political character of a single cultural figure: they are about dislodging both the book and the artist from the position of exemplar. Hong’s caution not to read Citizen 13660 through a single lens clarifies the pressures of exemplarity as a representational mode, which can attempt to redeem ambiguous or close-mouthed texts by forcing them to speak.

Although the museum’s physical layout leads the visitor straight from redress to Okubo, JANM seems to follow Hong’s caution not to enclose the artist within the political lens of redress. The curatorial writings about the exhibit are relatively circumspect on Okubo’s politics; they describe the book as “groundbreaking” for being “the first book-length account on America’s concentration camp from the perspective of a former incarceree” and “an early example of a graphic memoir,” not for being a self-evident critique of the state.

|

| Memorial service for James Wakasa |

|

| Detention room filled with departing residents |

What did it mean to excise those slight elaborations on “the Wakasa case” from the final publication? And what can readers today make of such an elision, in this already famously elliptical work? Against the backdrop of its various political mobilizations (re-domesticating alienized incarcerees, testifying towards redress), Citizen 13660 might be best characterized by its oscillations and reticence––qualities that JANM’s exhibit faithfully reflects and interrogates through its attention to revision and editorial process. JANM’s Education Unit has designed a wonderful activity guide that asks visitors to participate in slow examination of Okubo’s drawings through activities in “close looking,” comparison between early sketches and final versions, and even invitations to draw one’s own illustrations from Okubo’s captions.

Over the decades, Citizen 13660 has been made a representative of multiple political/racial narratives––narratives not obviously cosigned or directly produced by the work itself. These interpretive frames are partly external impositions on the book, but they are also generated in large part by the work’s odd combination of documentation and reticence. A strategy of “documentation through reticence,” in fact, might be fitting to stress the scientist’s objectivity in Okubo’s textual voice. Or maybe “reticence through documentation”: the book rattles off a steady rhythm of particulars to fill incarceration’s empty time. “You had to work hard to keep yourself going, and to keep from thinking,” Okubo said in a post-publication interview. And as Greg Robinson observes, “Okubo may not have been referring simply to her camp experience,” but to the stifling representational burden of Americanizing/humanizing incarcerees.

|

| Landscaping with trees |

Another way of looking at Okubo's reticence is as a strategy of abstraction––as a stylistic register that responds to the pressures of racial exemplarity. Talking about Citizen 13660 in terms of abstraction may seem odd, given the work’s obvious claims to figurative representation (as documentary) and its obsessive interest in particulars: barrack and room numbers, curfew times, toilet arrangements, wages. Its text and image move at different paces, though, and rather than elaborating or contextualizing the moments depicted in each drawing, Okubo’s captions often direct the reader and characters onward, onward, onward, at a brusque pace something like a punchline.

“Everyone was building furniture and fixing up barracks and stalls. Many of the discomforts of the camp were forgotten in this activity.”

“Letters from my European friends told me how lucky I was to be free and safe at home.”

“The incomplete partitions in the stalls and the barracks made a single symphony of yours and your neighbors’ loves, hates, and joys. One had to get used to snores, baby-crying, family troubles, and even to the jitterbugs.”

Her drawings, by contrast, loop the eye into compositions that Hong describes as “[w]himsically Matryoshka-like in visual architecture,” with figures whose gaze and movement rarely advance in a single direction––and which almost never resolve into any legible kind of effect. Okubo threads her readers between progressive and melancholic time: we neither move briskly into the future (as the book’s final caption seems to promise), nor do we stay endlessly in some fractured, traumatic moment.

In his essay on abstract comics, Jan Baetens introduces the idea of abstraction at the level of sequence rather than just the individual image. Abstraction as a sequential strategy can serve narrative ends by “foreground[ing] an enigma” and by withholding connections between image-moments, although in Baeten’s model, abstraction and narrative are always in “active conflict.” Abstraction in Okubo’s proto-”graphic memoir” doesn’t mean a total absence of either figuration or narrative; I mean something like a looseness between forms and what those forms legibly, identifiably signify. Not a lack (of particulars, of lines, of images), but a loose connection: resemblance under reconstruction; narrative in double vision.

|

| Sewage system repairs |

At the level of image, Okubo works out a visual shorthand for Japanese faces that refuses the specificity of portraiture, favoring instead a semi-opaque, semi-abstracted cartoon style that consciously both resembles and revises the racial caricature Okubo saw in comics. At the level of narrative, Okubo’s temporal “mixed messages” loosen the hold of progressive time, which preferred to frame internment as a momentary lapse, and which hoped to smoothly re-domesticate its internal aliens through their post-camp dispersal. Her layered and contradictory sense of time rehearses internment’s own absurd and distorted relationship to linear temporality; the minor but multiple incongruities between captions and drawings eat away at the narrative sense a reader attempts to make out of panels, pages, incidents, particulars. For both the singular and sequential registers of representation, abstraction emerges as a way of managing expectations: meeting the narrative demands of reinstated citizenship and yet clearing room for alternate narrative connections.

As some early book reviews, displayed in the exhibit’s final room, were keen to observe, Okubo skirts obvious caricature or anguish in favor of “tolerance and restraint.” Her few moments of straightforward outrage are all that keeps the book from being “inhumanly quiet,” one reader said. These reviews seem to sense irony where they expected feeling (ironized state critique would later become the conventional reading), but they largely emphasized––and admired––the book’s apparent lack of bitterness. Of the reviews on display at JANM, one even offers Citizen 13660’s “touches of humor” as proof that Okubo “rises above resentment and rancor.” The relief is palpable amid the slight confusion.

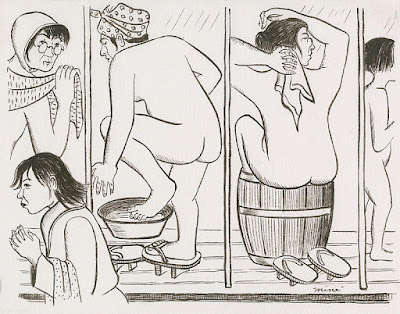

|

| Bathing in tubs |

Not on display (but relevant here) is a 1947 review by Setsuko Matsunaga Nishi, a sociologist who was incarcerated at Santa Anita during the war. Nishi also notes the book’s “commendable objectivity,” but she complains that among these precisely observed discomforts of the camps, what “is not evident to most readers is the disillusioning torment that evacuation meant to them.” Nishi, of course, was right: Citizen 13660 refrains from foregrounding tragedy. And perhaps most readers were happy to read the book as a funny and humanizing, if oddly reserved, account of a nation’s embarrassing lapse. Citizen 13660 did on one hand facilitate the human empathy and “common ground” upon which a progressive American time could be plotted. Yet it also dealt closely and actively with the very logic of racial identification and exemplarity that has followed the book through its initial period of publication and its Redress-era resurgence. In its very title, Citizen 13660’s abstracted identification with/of Okubo brings some irony to the close association reviewers made between the artist and her representational strategies of restraint, humor, and (apparently) forgiveness. Citizenship, already an abstract form of legal personhood, becomes one half of an oxymoronic identification.

One of Nishi’s more disparaging remarks describes “the very facile nature of the book” as being in conflict with the “deep subjective meaning” of the art. “If the reader were to verbalize the significance of some of the illustrations,” she writes, “he might be surprised at the bitter irony.” What these drawings signify––what they are pictures of, exactly––is not immediately clear or stable. There’s no way to resolve its rhetorical shape into either a 1980s voice of oppositional critique or the 1940s one of redemptive propaganda. What looks from one angle like redacted/repressed tragedy looks from another like “good humor” (a particularly oblique and unfixed mode of historical relation) and from yet another like “bitter irony,” to use Nishi’s phrase. Okubo’s reworking of figuration and narrative sequence, which I’ve identified as a semi-abstracted style, disorient and disperse anything more than a bare sense of narrative facts and feeling. Katherine Stanutz describes this effect as an inscrutability open to future reinscription––“what is ungrievable in 1946 gradually becomes grievable in the 1970s and 1980s”––but to me, the lightness of Okubo’s text reads not as a deferral of grief, but as grief’s less hallowed (and less legible) form.

Near the entrance to the exhibit, three expressive charcoal drawings from Okubo’s camp era-corpus hang on display––all of them done at a much higher and more recognizably “fine arts” register of abstraction. In one, a gaunt, childlike figure presses its face and hands against the picture plane; in another, an adult and a child peer crookedly out through barbed wire that divides the picture into multiple, pronged horizons. The crosses used to denote the barbs are integrated into the figures’ furrowed brows. These emotive drawings are especially instructive context for the cartoon style she chose for Citizen 13660, which is stiffer, cooler, and more line-driven in its mark-making. Like the charcoal drawings, Citizen 13660’s illustrations still flatten the depth of field, emphasizing the compressed dimensions of the page over that of three-dimensional space, but its characters rarely bear the same expressions of outright anguish, nor do they look directly out at the reader. Instead, the figures of Citizen 13660 are almost always engaged in a gesture of work, of adjustment. Even rest becomes just another task that passes time.

You can’t, as of this writing, visit the Okubo exhibit in person––JANM is temporarily closed due to the rise in COVID-19 cases here in the US.* But JANM’s digital collections host a rich archive to explore, including Okubo’s drawings as well as many other collections, and the museum is hosting a series of online events/workshops related to the Citizen 13660 exhibit. I’m grateful to their work in putting together all of these routes into Miné Okubo’s work, which still has so much to teach us.

A version of this review will appear in the print edition of IJOCA.

*The museum will reopen on February 1, according to a staff member.

Thursday, January 13, 2022

Book Review - The Stan Lee Universe by Danny Fingeroth and Roy Thomas (eds.).

Danny Fingeroth and Roy Thomas (eds.). The Stan Lee Universe. Raleigh: TwoMorrows Publishing, 2011. 175 pp. ISBN: 978-1605490298. US $8.99. https://twomorrows.com/index.php?main_page=product_info&cPath=123_140&products_id=934 (only digital version still available)

Reviewed by Michael Kobre

A common image of Stan Lee for hundreds of millions of fans all over the world who've seen an Avengers or Spider-Man movie or who've read a few Marvel comics, is that of an avuncular genius who created a whole new pantheon of myth—"this generation's Homer," according to a Princeton student in 1966. Another image, distilled from the remembrances of some of his collaborators and from the comic book industry's long history of exploiting its creators, has shadowed Lee as well. In this version of the story, he's a carnival huckster shilling lies and stolen goods, claiming credit for work that isn't his, while reaping the wealth and fame that should have gone to the artists who really created Marvel Comics. This version of Stan Lee, in fact, looks a lot like Funky Flashman, a devious and numbingly loquacious promoter decked out with a toupee and a fake beard—a caricature of Lee, that is—who tormented Jack Kirby's Mister Miracle, one of the heroes Kirby created for DC. Kirby, whose art defined Marvel at least as much as Lee's words, had quit working for Marvel in 1970, fed up at last with all the broken promises of more generous financial rewards and creative credits for his work. And it's this version of Stan Lee as well who's the protagonist of Abraham Riesman's 2021 biography of Lee, True Believer: The Rise and Fall of Stan Lee. Carefully researched and gracefully written, Riesman's biography nevertheless insistently views Lee through the darkest possible prism. For Riesman, Lee is, above all, a con man and liar. As Riesman writes in his book's prologue, "[Lee] lied about little things, he lied about big things, he lied about strange things, and there's one massive, very consequential thing he may very well have lied about. If he did lie about that last thing—and there's substantial reason to believe he did—it completely changes his legacy" (12).

At the core of this divide over Lee's character and work is, of course, that other long-running argument about the respective contributions of Lee, Kirby, Spider-Man artist Steve Ditko, and others to the creation of Marvel's characters and worlds. Lee's "Marvel Method" of creating comic books, in which artists like Kirby and Ditko would work from loose plot descriptions generated in increasingly-rushed conversations (which may or may not have ever been written down) meant that Marvel's artists had unprecedented freedom to shape and pace the stories they told, in a form of creation that Charles Hatfield has called "narrative drawing" (Hatfield 15). But the free-wheeling, improvisational nature of the Marvel Method also meant that Lee's own contributions were unclear, in spite of the line in so many credit boxes in so many Marvel comics that claimed that they were "Written by Stan Lee" (or "Smiling Stan" or "Stan the Man" or any of the other affectionate sobriquets that Lee employed in credit boxes). Yes, Lee added the dialogue and captions after the artists submitted their pages, but what role had he really played in conceiving the characters and plots? By 1989, Kirby said flatly that Lee's role hadn't been much at all. "I've never seen Stan Lee write anything," Kirby told Gary Groth for a Comics Journal interview. "I used to write the stories just like I always did" (Groth 37). In True Believer, Reisman even questions Lee's role in creating Fantastic Four #1 in 1961, the book that launched the Marvel era. "…[O]utside Stan's own oft-repeated words," Reisman writes, "there is currently no known evidence that he created the premise, plot, or characters that appeared in Fantastic Four #1. No presentation boards, no contemporary legal documents, no correspondence, no diary entries. Nothing" (105).

In light of all the questions raised again by Riesman's biography and as part of the inevitable ongoing revaluation after Lee's death in 2018, it's helpful to look back at a 2011 collection of Stan Lee interviews, tributes, critical examinations, and miscellanea from Lee's archives, The Stan Lee Universe. Edited by Danny Fingeroth, whose own 2019 biography of Lee, A Marvelous Life: The Amazing Story of Stan Lee, offers a more conventional portrayal than Riesman's, and by long-time Marvel writer and editor Roy Thomas, who describes himself here as Lee's "left-hand man" in Marvel's glory days, The Stan Lee Universe is, not surprisingly, an unequivocally admiring portrait of Lee. Arranged more or less chronologically, the collection follows Lee's career from a 1957 profile which focuses on the short-lived comic strip about a group of cub scouts, Mrs. Lyons' Cubs, that Lee created with artist Joe Maneely (Lee, always hungry for recognition, notes with "very great satisfaction" in the profile that the strip "has been approved by the chief Scout executive") to at least brief references to some of his final projects, including his mostly forgettable reality shows Who Wants to be a Superhero? and Stan Lee's Superhumans. Along the way, we also see family photos; notes Lee exchanged with film directors, including Alain Resnais, James Cameron, and Oliver Stone; pages from an unpublished screenplay for Resnais; an advertisement featuring Lee for Hathaway shirts; stills from a 1976 razor blade commercial, also featuring Lee; pitches for unrealized Marvel projects from Will Eisner and Richard Corben; and even a note from Lee to the president of United Airlines praising a stewardess who helped Lee and his wife Joan when she became ill during a flight. Among other odd discoveries in this material is Lee's suggestion to Resnais that he direct a Spider-Man movie starring Henry Winkler.

But the heart of the book—as the center of Lee's story always will be—concerns his years as Marvel's most prominent scripter and its editor-in-chief. And it's on this subject that the interviews, analyses, and testimonials in the book do, in fact, help us understand a little more clearly the significance of Lee's contributions to the creation and rise of Marvel Comics. The Stan Lee Universe accomplishes this though, whether intentionally or not, by shifting the terms in which we might consider those contributions. Although there's a fine analysis by Peter Sanderson late in the book of Lee's style in dialogue and captions—Sanderson is particularly good at discussing Lee's use of the words "naught" and "smoldering" in a Thor caption—Lee in the interviews and the other artists and writers in their various testimonials don't actually have much to say about his work as a writer. There are general comments about the importance of characterization and vivid dialogue, but there's no sustained conversation about any individual story. Instead, what the book illuminates is Lee's work as an editor, shaping some of Marvel's signature characteristics (including ones essential to its wildly successful screen adaptations) and, of course, defining its brand.

In remembrances of Lee, for instance, by writers like Thomas, Denny O'Neill, and Gary Friedrich and by such artists as Gene Colan, John Romita, and Herb Trimpe, Lee is consistently portrayed as an exacting editor with a clear vision of what he wanted on Marvel's covers, in its plots, in its art—Trimpe remembers Lee tossing pages of layouts into a trash can because Trimpe had used too many small panels—and even in the placement of dialogue and captions. For the writers, in particular, Lee was a teacher also. "He'd call us in and have us stand by him in front of the drawing table and go over the completed artwork of a story we'd written or one he'd written," Friedrich recalls, "and he'd edit it with us standing there, explaining any changes he'd made, why he put a balloon in a certain place, why he had a character say this rather than that, etc. One thing in particular I remember that he continually drove home was to always move the story forward. 'Every word that's spoken should be for the purpose of moving the story along,' he'd tell us again and again" (54). Even in later years, when Lee would receive almost finished pages, Thomas remembers, "the fact that Stan hadn't seen the dialogue and captions before they were rendered in ink in no way inhibited him from making changes … substantial changes" (50).

Lee was, of course, also a master at developing Marvel's brand. "Thinking back," he says in a 1974 interview, "the whole thing was treated like an advertising campaign. The catch phrases, like 'Make Mine Marvel' and 'Face Front' and 'Excelsior' …I did it unconsciously, but it was all in the direction as though … I was building a product. I wanted to make Marvel Comics a product that people … would love" (124). In a detailed analysis of how Lee shaped Marvel's letter pages and then conceived and wrote the Bullpen Bulletins Page, which in 1967 began including "Stan's Soapbox," David Kasakove writes that "Stan Lee's editorial voice—at once frantic, comic, self-deprecating, tongue-in-cheek, good-natured, wildly self-congratulatory and (sometimes) moralistic—was a years-long tour de force, the glue that held the Marvel Age of Comics together" (130).

Reading The Stan Lee Universe also reminds us of how Lee's editorial vision helped shape Marvel's signature characteristics in the 1960s, innovations that would effectively redefine the conventions of virtually all superhero narratives in comics and later in other media. Looking back in a 1974 interview, in the context of retelling his familiar story about creating the Fantastic Four (and, as usual, taking credit for the characters' conceptions), Lee singles out his insistence on a kind of realism. "I tried to do everything I could to take these super-powered characters and in some way to make them realistic and human," he says. "To have them react the way normal men might react if these normal men happened to have superhero powers" (124). But while the respective contributions of Lee, Kirby, and Ditko to the creations of the Fantastic Four and Spider-Man will always be—at least to some extent—uncertain, the kind of realism Lee describes, particularly in Marvel's early years when he was practically the company's only writer, seems to have more of his imprint. We hear Lee's voice, I'd argue, in scenes like Spider-Man's failed attempt to cash a check in his name in Amazing Spider-Man #1 or a scene in Fantastic Four #9 that Lee recalls in that 1974 interview when "They're evicted from their headquarters because they can't pay the rent because Reed Richards invests all their reward money in stocks and the markets take a nosedive" (124). For all of the qualities of Marvel Comics that flow into the solo work of Kirby and Ditko after they left Marvel, there are no moments like these: poignant, comic scenes, anchored in mundane realities and steeped in a kind of wry melancholy that turns superheroes into Yiddish shlemiels.

Moments like these, however, would become less prominent as Lee became more involved in promoting Marvel Comics than in writing them and as Marvel's universe expanded too. But that concept of a shared universe, which was as much about branding and marketing as it was about storytelling, was clearly Lee's innovation. As he says in a 1968 interview, "… what we try to do, and I think we were probably the first at this, we try, even though they're different characters in different magazines, and possibly even living in different places, we try to make it all like one little world in which these characters exist, the Marvel world …" (44). Even Reisman concedes that Lee deserves credit for Marvel's shared universe: "Kirby never took credit for that idea—indeed, his assistant and biographer, Mark Evanier, says Kirby found it cumbersome and irritating, because it forced him to incorporate other people's ideas into his own comics. But Stan was enormously proud of the notion of the Marvel Universe and maintained it in all the superhero books" (129). Over time too, in light of Marvel's success, all superheroes existed in shared universes like this, and it's no exaggeration to say that the translation of this concept to the Marvel cinematic universe is a vital component of Marvel Studios' success on-screen, a narrative convention that's since been adapted, for good or ill, in so much other franchise storytelling in movies and other media forms.

So what about that other question then? Who really created Marvel's characters and the universe-spanning epics they inhabit? Lee in the interviews here mostly tells the familiar story that he created the Fantastic Four and so many other characters. As the years pass in the book, we see him growing into the persona that would consume him for the rest of his life, as, for instance, in a 1974 interview, when he considers at length how he's absorbed Shakespeare's influence. But Lee is also careful to acknowledge how Marvel's artists, especially Kirby, co-created its stories. "… [T]he artist is part writer—" he says in a 1969 interview, "—he's breaking the story down as he sees it …" (78). In the earliest interview in the book, from 1965, Lee is remarkably open about Kirby's role in creating stories:

Some artists, of course, need a more detailed plot than others. Some artists, such as Jack Kirby, need no plot at all. I mean, I'll just say to Jack, "Let's let the next villain be Doctor Doom" … or I may not even say that. He may tell me. And then he goes home and does it. He's so good at plots, I'm sure he's a thousand times better than I. He just about makes up the plots for these stories. All I do is a little editing… I may tell him he's gone too far in one direction or another. Of course, I'll occasionally give him a plot, but we're practically both the writers on the things. (11)

The documentary evidence in The Stan Lee Universe, however, doesn't settle anything. The book reprints a plot synopsis for Fantastic Four #1, which Reisman describes as "a curious document with a questionable history" that may have been written years after the comic's publication (106). Indeed, Roy Thomas' notes about the document here do little to clarify its provenance, as Thomas tells us how he was summoned into Lee's office one day late in the '60s so that Lee could show him the synopsis which Lee claimed to have found in a filing cabinet the night before—although Thomas does note that the synopsis looks like other typed plot summaries from the early '60s that Lee had previously shown him, including one for Fantastic Four #8 that's also included in The Stan Lee Universe. If anything though, other documents in the book don't make much of a case for Lee as a writer. Reproductions of pages from occasional prose stories he wrote for Marvel publisher Martin Goodman's other magazines and from Lee's unproduced screenplay for Resnais are all pretty routine stuff, mired in genre conventions or heavy-handed stereotypical characterizations. For that matter, the reproduction of materials from Lee and Kirby's last collaboration, a 1974 Silver Surfer graphic novel published by Simon and Schuster, strongly suggest that the book's story was mostly Kirby's, as he carefully details the plot in lengthy typed letters accompanying his artwork which are addressed to "Stanley" (and signed "Your pal, Jack") (153-155).

Ultimately, the exact details of Lee's collaborations will never really be known. As Thomas notes in his comments on the Fantastic Four #1 synopsis, by 1965 Lee "was increasingly dispensing with written synopses, with Marvel artists often working merely from brief conversations, in person or over the phone" (15). Instead of written documents, we have Gene Colan's memory of recording phone calls with Lee or John Romita, Jr.'s memories of his father's anxiety after driving away from a plot session with Lee. "Oh, God, I didn't write any of this down," Romita, Jr. recalls his father saying, "how am I gonna remember all of this stuff?" (108). But if we must continue to dwell in uncertainty about what exactly transpired in Lee's work with Kirby, Ditko, and so many others, The Stan Lee Universe is an informative and entertaining field guide to that territory. Copiously illustrated, it brings to life again Lee's crowning moment as he helped to usher in the Marvel Age of Comics. If, as Reisman asserts, Lee's impulse to exaggerate his claims as a creator while failing to properly recognize his own achievements as Marvel's editor "was a core tragedy of Stan's existence and legacy," The Stan Lee Universe helps us at least to see those achievements more clearly (67).

References

Fingeroth, Danny, and Roy Thomas, editors. The Stan Lee Universe. TwoMorrows Publishing, 2011.

Fingeroth, Danny. A Marvelous Life: The Amazing Story of Stan Lee. St. Martin's Press, 2019.

Groth, Gary. "I've Never Done Anything Halfheartedly." The Comics Journal Library: Jack Kirby, Fantagraphic Books, 2002, pp. 18-49.

Hatfield, Charles. Hand of Fire: The Comics Art of Jack Kirby. University Press of Mississippi, 2012.

Riesman, Abraham. True Believer: The Rise and Fall of Stan Lee. Crown, 2021.

A version of this review will appear in print in IJOCA 23:2.

Book Review - The Life and Comics of Howard Cruse: Taking Risks in the Service of Truth by Andrew Kunka

Andrew J. Kunka. The Life and Comics of Howard Cruse: Taking Risks in the Service of Truth. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2022. 196 pp. $29.95, $69.95. < https://www.rutgersuniversitypress.org/the-life-and-comics-of-howard-cruse/9781978818859>

Reviewed by Christopher Roman

Kent State University

Critics agree that Howard Cruse is an important figure in the wider field of comics, and especially so in the history of underground and queer comics. Yet there are only a few articles devoted to Cruse's works (my quick MLA search put that number at eight, though I am sure there are more to be found in the wider world of the internet). Andrew J. Kunka's book, The Life and Comics of Howard Cruse, comes at a critical time, published two years after the 25th Anniversary Edition of Stuck Rubber Baby and three years after Cruse's death in November 2019. As Kunka writes in his preface, his plan was to have an extensive interview with Cruse published in this collection. However, Cruse had died before interviews could happen. Kunka, though, had generous support from Cruse's husband, Ed Sedarbaum, who was able to supply page scans for this collection. Kunka's ability to connect with so many people who were fans and supporters of Cruse make this collection essential to the study of his short-form comics.

The eight critical works that I mentioned above focus on Cruse's masterpiece Stuck Rubber Baby, and rightfully so. Stuck Rubber Baby is a premier graphic novel grappling with tough issues of racism and queer life in the Civil Rights-era South. It serves as not only an important historical graphic novel, but provides insight into the intersections of black and gay Southern life pre-Stonewall. Yet, what Kunka has managed to do in his critical anthology is open up Cruse's work beyond Stuck Rubber Baby to account for Cruse's short-form work which is not as often discussed or anthologized except for his short comic "Billy Goes Out" (see, for example, Justin Hall's collection No Straight Lines [2012]). Cruse created many more comics with an impressive range of themes and styles, apparently all of which Kunka accounts for in this book.

As Kunka mentions in his brief Introduction, short form comics do not often get critical attention, and even when collected, do not stay in print very long compared to 'graphic novels.' Cruse's collections, Wendel All Together (1985), Dancin' Nekkid with the Angels (1987) and The Other Side of Howard Cruse (2012) are all out of print. Cruse even self-published From Headrack to Claude (2009), another of his short form comics collections, in order to keep those comics circulating. Kunka's book serves as a foundation to further work on Cruse's extensive short form comics. This book fills in the missing critical background on Cruse's life and his work that display his range of creativity, innovation, and humor, as well as his connections to the nascent worlds of underground and queer comics creators.

Chapter one is a critical biography of his life. Kunka recounts Cruse's early life in Birmingham, Alabama, and his importance to underground comics as a young cartoonist. After creating gay-themed Christmas cards, Cruse ventured out into queer comic books, a path that had been paved by lesbian comics creators in the '70s such as Mary Wings, Lee Marrs, and Roberta Gregory. He worked with Kitchen Sink Press to establish Gay Comix in September 1980. Gay Comix was profoundly influential as it not only provided a forum for queer comics creators, but also influenced future queer cartoonists, some of whom became much better known than him, such as Alison Bechdel. Cruse's push to have a forum for queer creators to focus on queer culture and relationships could be considered a breath of fresh air in an underground comix world rife with misogyny, racism, and homophobia.

The remaining chapters are a thematic look at Cruse's work, with full page art samples (some in color). Kunka's critical commentary leads each chapter, and then he discusses the stories with historical context and more specific critical prose. Chapter two focuses on "Autobiographical Fiction/Fictional Autobiography." Cruse's approach to autobiographical comics undermined what are now traditional genre conventions as accepted in memoirs. While there may be a character named Howard in these short form comics, there is sometimes a twist into a fantastical, or humorous reveal, which questions the stories' claims to objective truth. Kunka includes such autobiographical comics in this section as "Jerry Mack," "The Guide," and "Then There Was Claude." Each of these comics plays with autobiographical genre while showcasing Cruse's array of drawing and storytelling styles.

Chapter three focuses on work that can be classified as "Commentary and Satire." Cruse's comics regularly commented on the politics of his time. Kunka links Cruse's more overtly social and cultural commentary works to political and educational comics. In the selections provided in this chapter, Cruse addresses issues surrounding the AIDS crisis, gay activism and queer culture, the news media, and death. This section includes "Billy Goes Out," Cruse's masterclass of a short form comic, where he uses time shifts and a drawing style to seamlessly tell a story of 1980s cruising culture. Another humorous story is "Dirty Old Lovers" in which Cruse comments on the treatment of older gay men in a gay community obsessed with youth, and a media that wants to present gay men as respectable.

Chapter four addresses Cruse's "Parody" work. Cruse's style can be thought of as cute, a derivation of the long-lasting bigfoot style. In these works he uses his "cute" style to borrow characters from early comic strips such as Lulu, Casper, and Nancy to poke humorous fun at consumer culture, the dark side of children's comics, and the sexuality hidden therein. This chapter also includes an essay Cruse wrote on the importance of parody where he likens his parody to political cartooning, but aimed at the art world.

In all of these chapters, Kunka balances narrative analysis with comics analysis, pointing out where Cruse uses panel borders unconventionally, or how his work with stippling and cross-hatching was groundbreaking. Kunka's commentary balances Cruse's storytelling with his drawing work, showing how Cruse was the complete package, a true cartoonist. Kunka's work and critical commentary is an essential read for those interested not only in Howard Cruse, but in how his work impacted a generation of artists, especially in how important Cruse was to helping create the genre of queer comics.

A version of this review will appear in print in IJOCA 23:2.