Articles from and news about the premier and longest-running academic journal devoted to all aspects of cartooning and comics -- the International Journal of Comic Art (ISSN 1531-6793) published and edited by John Lent.

Sunday, February 9, 2025

Lent Comic Art Classification 2017 Edition online as free ebook

Thursday, February 6, 2025

Lucca Comics & Games 2024 Festival Review: "The Butterfly Effect"

reviewed by Bart Beaty and Rebecca Sullivan, University of Calgary

Lucca Comics & Games 2024. Lucca, Italy. October 30 – November 3, 2024.

https://www.luccacomicsandgames.com/

The Butterfly Effect

Our biggest takeaway

after visiting Lucca Comics & Games for the first time is that we failed as

parents by not bringing our kid. This is a festival for today’s

manga-anime-gaming obsessed generation. While it may not be comics enough for

some, the total experience is breathtaking and well worth bracing the mind-boggling

crowds. The 2024 edition of Lucca Comics & Games, the largest comic book

festival in Europe and the second-largest (after Tokyo’s Comiket) in the world,

took place from October 30 to November 3. The history of the Lucca Comics &

Games is complex, tracing back to the Salone Internazionale del Comics in 1965,

which was also held in Lucca. A new festival, Lucca Comics was created when the

Salone moved to Rome in the mid-1990s, quickly growing larger and more

prominent than the original event. In 2006 the two events reconciled, with the

Salone returning to the walled city of Lucca. What began as a comics event is

now more accurately described as a fan culture event with some comics elements

tacked on. Indeed, the comics, despite their prominence in the name, can feel

slightly residual.

The festival has grown exponentially

since that the merger almost twenty years ago. Attracting about 50,000

attendees in the mid-2000s, it sold 275,182 tickets across its five days this

year (down from the record high year in 2022). For a town of 89,000 people,

this is quite the logistical challenge. School is cancelled during the week of

the festival, with many locals abandoning the city and renting their homes to

attendees, while thousands pour in every day on the train. If you go: Plan to

take the train (book in advance) and pack light as taxis are barred from inside

the walls and only local cars are allowed. Order your wristbands well in

advance as well since they will sell out and staff scrupulously check outside

every tent. This is not an event to be dropped in on at the spur of the moment.

The enormity of the

crowds makes the festival a considerable challenge, with long queues for most

of the popular tents. This year, we counted sixty-four distinct exhibition

spaces across the entirety of the town. That does not include the expansive

Japan Town outside the walls – although Japanese producers were strongly

represented within the main site. The town was subsumed by tents, mostly

controlled by single exhibitors: Lego, Nintendo, The Cartoon Network, Hasbro,

Funko, Crunchyroll, and Samsung among many others. Some were targeted

promotions – like Netflix dedicating a large tent just to promote the second

season of Squid Game – and many offered festival exclusive merchandise. Lines

stretched for hours (the J-Pop tent must have been at least a three hour wait)

that could test the patience of even the most dedicated consumer. We queued for

almost an hour to buy a limited-edition Dungeons and Dragons t-shirt as

a gift for our son. Maybe we’re good parents after all.

The scope of the tents

is encapsulated by the festival’s stated aims: “The community event is

dedicated to comics, games, video games, fantasy books/fantasy novels, manga,

anime, animated movies, tv series, and cosplay.” Cosplay is probably misplaced

as last on that list given that a very significant percentage of the attendees

were participating cosplayers representing a wild array of pop culture

interests. Every afternoon in the square, in front of one of the many churches,

a cosplay event unfolds celebrating a different fandom. We watched a parade of

Harry Potter fans, ranging from very young children in store-bought wizard hats

to adults with highly-detailed costumes evincing hundreds of hours of work.

Everyone seems welcome.

While “comics” may lead

the title of the event, it does not much feel that way on the ground, where

video games and television seem to be the predominant interest. Several Italian

publishers host their own booths at Lucca, including Panini, Bonelli, Tunué,

and Star Comics. Of these, Panini and Bonelli had, by far, the largest and

busiest booths. Panini is the Italian publisher of both Marvel and DC’s comics,

offering much nicer editions of the works than either of those publishers sell

in the United States. They also do a large business with Disney-related works

for younger children and had long lines of autograph seekers stretching well

outside the tent into the square.

Bonelli, the venerable

Italian publisher of Dylan Dog, Tex Willer, Nathan Never

and dozens of others, also offers a wide array of products, including deluxe

editions of classic material. The Padiglione San Martino had a much larger tent

housing more than two dozen smaller comic book publishers from across Italy,

while the largest tent could be found at the Padiglione Napoleone, hosting

about sixty exhibitors including Canicola, Coconino Press, Rizzoli Lizard,

Humanoïdes Associés, and Fantagraphics. This was the primary centre of gravity

for comic book sales across the festival and, since it is a tent erected in a

town square, it revolves around a statue of Napoleon that overlooks the

commercial chaos.

As with other European

comics festivals, Lucca Comics & Games played host to a series of

exhibitions. In general, these were much smaller than what can be found at

Angoulême or Fumetto. Seven exhibitions took place in the Palazzo Ducale, each

following essentially from one room to the next and hung in front of the

permanent exhibitions of classical and renaissance Italian painting. The result

was sometimes jarring but oftentimes provocative juxtapositions. While the

Palazzo entrance was oddly difficult to find, especially as the street crowds

grew larger and larger by the hour, the exhibitions were well worth it and

generally did not have lines.

Press Animae to Play featured a small

selection of work by Yoshitaka Amano as a tease for a much larger Milan

exhibition opening about two weeks after the festival. About two dozen works,

including early anime cels and more recent covers for Sandman: The Dream

Hunters filled a single room.

Contrappunti showcased the work of

Carmine di Giandomenico, who has made a name for himself in the American comic

book market with work for Marvel (Battlin’ Jack Murdock; Magneto)

and DC (Flash).

A small show celebrating

five decades of Les Humanoïdes Associés followed, with a tight focus on Métal

Hurlant and an emphasis on its Italian contributors (Tanino Liberatore,

Magnus, Cecilia Capuana, Brandoli and Queirolo, and, of course, Hugo Pratt)

with a few pieces by well-known French cartoonists like Frank Margérin and Möebius.

Two rooms showcased

twenty years of winners of the Lucca Project Contest for young authors,

celebrating the more than 3,600 aspirants who have entered over the years.

Kalimatuna highlighted the work of

three female cartoonists from Morocco: Takoua Ben Mohamed, Zainab Fasiki, and

Deena Mohamed. Unapologetically feminist, the works on display emphasized the

impact of gender-based violence on Moroccan women.

An exhibition of the

work of Kazu Kibuishi followed, with most of its attention given appropriately

to Amulet. Significantly here, Kibuishi’s framed pages (black line art

on white pages) were displayed on backdrops of blown-up digital prints of the

colour version of the final pages, drawing easy attention to the significant

differences between the original page and the final project. We had never seen

original comics art presented in this manner, and it was tremendously smart;

particularly given that so much work in Amulet is accomplished by the

colorists.

|

| Amulet by Kazu Kibuishi (above and below) |

Finally, the work of

Francesca Ghermandi was found in Il Pianeta Intergalattico, including a

range of her work across her lengthy career working for Frigidaire, Mondo

Gomma, and Linus.

Across town, at the

Chiesa dei Servi, the major exhibition of the show could be found: Gateway

to Adventure: 50 Years of D&D Art. When we first learned that the major

exhibition of the festival was related to games rather than comics we were,

frankly, disappointed. That feeling disappeared immediately upon entering the

space of the church.

The exhibition featured

the first public unveiling of the collection of Matthew Koder, a Citibank

executive who has extensively gathered D&D related artworks. It showcased

more than one hundred works - mostly oil paintings - from the 1970s to today.

The breadth of the collection is astonishing, including the oil paintings that

were used for the original editions of the Dungeon Master’s Guide and Player’s

Handbook, original art from the interiors of those and other early TSR

publications, the covers of early issues of Dragon Magazine, various

D&D modules and novels, and the Dungeonmaster game and television

series. The show concluded with paintings for Magic: The Gathering cards

in recognition of the ownership of the property by Wizards of the Coast. At the

end of the church a small group wearing headsets broadcasting across the church

played a campaign while attendees admired the work on the walls.

Broken into a series of

eras, the Koder Collection represented the graphic style of every revision of

the game and its rules. It was a truly magnificent exhibition, all the more

remarkable that it is held in a single collection. With luck, this show will

travel broadly as it would find an enthusiastic audience in many locations.

All of this, of course,

is only to scratch the surface. Given the vast scope of the show there were

entire sections that we never entered, from the LARPers gathered on the town’s

walls practicing their swordplay to the children playing on the Cartoon Network’s

elaborate adventure set (source of most of our parental guilt). Every

conceivable geek fandom was represented, from the traditional collector’s tents

selling vintage comic books and original art to the voluminous number of stalls

peddling t-shirts and imported Japanese anime figurines.

Exhibit review: Tove Jansson: Paradise

reviewed by Bart Beaty and Rebecca Sullivan, University of Calgary

Photos are by the reviewers except for Bird Blue (detail) which is from the Museum's website.

It

is all but impossible for visitors to Helsinki to avoid the influence of Tove

Jansson. A Moomin shop occupies a prominent location in the airport, while two

competing Moomin shops can be found in close proximity to the central train

station. Moomin figures can be found in bakeries and candy shops and

bookstores. The Moomins can be found peddling chocolate-filled peppermint

candies, organic oat snacks, coffee mugs, cutting boards, can openers, stuffed

toys, t-shirts, and wool socks. They are everywhere and they are on everything.

Unsurprisingly, therefore, they were also in HAM Helsinki Art Museum.

From

October 25, 2024 to April 6, 2025, the top two floors of Helsinki’s primary art

space were given over to Tove Jansson: Paradise. Billed as an in-depth

look at Jansson’s public paintings, the show included a large number of

Jansson’s pre-Moomin paintings from the 1930s and 1940s while focusing

extensively on her career as a muralist.

Jansson’s

first Moomin book, The Moomins and the Great Flood, was originally

published in 1945 to no great success. Prior to that time, Jansson, the

daughter of a sculptor father and an illustrator mother, spent most of the

1930s in a succession of art schools in Stockholm, Helsinki, and Paris.

Following in the footsteps of her mother, she published illustrations in Garm,

a Finnish-Swedish satirical magazine from 1929 to 1953 while, at the same time,

exhibiting paintings in group shows. Jansson’s first solo painting exhibition

took place in 1943, two years before the first Moomin book was published. Two

years later, she painted her first mural at the Strömberg factory in

Pitäjänmäki, Helsinki. Tove Jansson: Paradise is interested in combining

all of these aspects of her career: the paintings from her student period

through her early professionalization, her career as a muralist working in

public spaces, and the early years and then rapid success of the Moomin books

and comics.

Jansson’s

first Moomin book, The Moomins and the Great Flood, was originally

published in 1945 to no great success. Prior to that time, Jansson, the

daughter of a sculptor father and an illustrator mother, spent most of the

1930s in a succession of art schools in Stockholm, Helsinki, and Paris.

Following in the footsteps of her mother, she published illustrations in Garm,

a Finnish-Swedish satirical magazine from 1929 to 1953 while, at the same time,

exhibiting paintings in group shows. Jansson’s first solo painting exhibition

took place in 1943, two years before the first Moomin book was published. Two

years later, she painted her first mural at the Strömberg factory in

Pitäjänmäki, Helsinki. Tove Jansson: Paradise is interested in combining

all of these aspects of her career: the paintings from her student period

through her early professionalization, her career as a muralist working in

public spaces, and the early years and then rapid success of the Moomin books

and comics.

Jansson’s

first two solo shows were arranged by Leonard Bäcksbacka at his Konstalongen

gallery 1943. The successful first show provided a boost for the young artist,

but the second solo exhibition in 1946 was not well received by either critics

or art patrons. The first several galleries of the exhibitions are given over

to a selection of her paintings as well as the contemporaneous illustration

work for Garm. Jansson’s paintings of this period are not immediately

recognizable as the work of the Moomin author but demonstrate a strong

influence of mid-century European modernism with their thick brushstrokes and

moody palette, while the illustration work – often topical and political –

shows stronger traces of the material that will develop in her children’s books.

Following

the display of her early easel paintings, the final room on the first floor of

the exhibition hosts two large frescoes as well as studies for the same.

Commissioned in 1947 by the restaurant in the basement of the Helsinki City

Hall, the two painting are titled Party in the Countryside and Party

in the City. These works begin to synthesize Jansson’s modernist and

folklorist aesthetics, providing a fascinating glimpse into the evolution of an

artist determined to become a critical and commercial success.

Party

in the Countryside

depicts eight figures frolicking in lush vegetation. The images are cartoony in

their representational simplicity and subtle pastel colour scheme - an abrupt departure

from the tone and style of her paintings following the unsuccessful second show.

The city scene is no less luxurious, depicting couples in gowns and evening

wear dancing on a flower strewn balcony.

The

two works, the artist’s first attempts at frescoes, participated in the massive

post-war reconstruction effort across Finland that provided unprecedented

opportunities for young artists. Jansson, who came from a well-connected family

of artists, benefitted tremendously (one might even leave thinking overtly) from

this social and political network.

The

only public commission known to have been awarded to Jansson on a competitive

basis was the Aurora Hospital murals intended for the new children’s ward.

Alone among the murals on display, these clearly capitalized on her growing

fame from the Moomin series. Play, painted in 1956, presented a series

of Moomin characters in the stairwell and the EEG room of the hospital. It was later

recreated at the Helsinki University Central Hospital when the pediatric ward

was relocated in 1997. At HAM, the mural was recreated once again on the

central staircase leading visitors from the first floor of the exhibition to

the second.

The

second floor of the exhibition was much more impressive than the first. A vast

open space with vaulted ceilings broken up by temporary dividers, this floor

showcased the immensity of the murals. Display cases of her sketches and highly

detailed notebooks invited viewers to contemplate the artist’s process. Jansson

typically produced preliminary sketches on paper and then worked through colour

schemes on cardboard before concluding with a 1:1 charcoal tracing that would

be transferred to the wall. Examples of each of these stages were on full

display here (most impressively the enormous cartoon of The Ten Virgins

with its pinpricks for the charcoal transfer readily apparent).

|

| Bird Blue, 1953 (detail). © Tove Jansson Estate. Photo: HAM / Maija Toivanen. |

Throughout the 1940s and into the 1950s, Jansson produced public art for restaurants, hotels, several schools, the Nordic Union Bank and an altar piece for the Teuva Church in Southern Ostrobothnia. She worked in fresco, fresco-secco (pigment applied to dry plaster), watercolour on glass, and oil on canvas. Over time, these works increasingly came to resemble work for which she is best known, and even to incorporate elements of the Moomin universe at the margins.

As

Canadians of a certain generation most of the waves of Moomin-mania missed us,

so we have no sentimental attachment to Jansson’s work. This turned out to be a

benefit as the exhibition is not about the Moomins really but about the artist

behind the phenomenon. There was no hiding Jansson’s sexuality, her sometimes

craven ambition, and her canny working of her socially powerful contacts in

both government and the art world. While Moomin die-hards might come away mildly

disappointed, the casual visitor gained incredible insight into

mid-twentieth-century Finland as it sought to distance itself from its complex

wartime status into an independent nation with its own distinct visual culture.

And, for those die-hards, there are Moomin mugs and mittens in the bookshop.

|

| Sketch for the Bird Blue mural, 1953. Commision for the canteen at Kila Swedish-language elementary school (today Karjaa co-educational school). |

Monday, January 27, 2025

Graphic Novel Review: Bald by Tereza Čechová (text) and Štěpánka Jislová (ill.)

reviewed by José Alaniz, University of Washington, Seattle

reviewed by José Alaniz, University of Washington, Seattle

Bald by Tereza Čechová (text) and Štěpánka Jislová (ill.); translated by Martha Kuhlman and Tereza Čechová. University Park, PA: Graphic Mundi, an imprint of Penn State University Press, 2024. 128 pages. $21.95. ISBN: 978-1-63779-080-9. https://www.graphicmundi.org/books/978-1-63779-080-9.html

Regarding the Czech comics domestic

scene, as recently as 2020 scholar Pavel Kořínek could credibly opine: “[A]ny

kind of subjective, personal recollection remains extremely rare. Czech comics

seem — at least on their most superficial level — curiously de-personalized,

de-subjectivized, with genre and fictional works predominant. For some reason,

there have emerged very few overtly personal, autobiographical comics in the

Czech tradition” (“Facets”: 91).

Such statements

are less credible today, thanks to more recent publications such as veteran

artist Lucie Lomová’s Every Day is a New Day: A Comics Diary (Každý

den je nový: komiksový deník, 2022) — a work as personalized, subjectivized

and autobiographical as anyone could want.

In fact, the

landscape was shifting even as Kořínek’s original assessment was seeing print.

That same year Czech publisher Paseka released the groundbreaking graphic

memoir Bez Vlasů (literally “Without Hair”) by writer Tereza Čechová[1]

and artist Štěpánka Jislová.[2]

It dealt in intimate detail with the memoirist’s life after a diagnosis, at 30,

of alopecia, an autoimmune condition that leads to hair loss. No comics work

like it (certainly not in long form) had appeared in the Czech lands before. It

would later win the Czech industry’s highest award, the Muriel Prize, for Best

Comics Work.

2024 saw the

English translation of Bez Vlasů, here rendered as Bald, from

Graphic Mundi Press. It is translated by Čechová and Martha Kuhlman, professor

of Comparative Literature at Bryant University in Providence, RI and one of the

leading US scholars of Czech comics.[3]

It makes sense

that Graphic Mundi, an imprint of Penn State University Press, would take up Čechová

and Jislová’s prize-winning work, given its Graphic Medicine focus. Penn State

is a major US node of the international Graphic Medicine movement, which

centers graphic narrative representations of illness, disability and related medical

themes.[4]

Bald

certainly ventures deep into this territory; the heroine Tereza navigates — at

times painfully — alopecia’s effect on her identity as a woman, love life, work

relationships and even her pocketbook. I found these scenes on the day-to-day economics

of her condition the most illuminating: she expounds on the cost of medication,

therapists, wigs, head coverings of different sorts. We also get fascinating

discussions on the hair of different races and ethnicities, as well as on the culture

and mythology of hair (Samson and Rapunzel are just the tip of the iceberg).

Bald

certainly ventures deep into this territory; the heroine Tereza navigates — at

times painfully — alopecia’s effect on her identity as a woman, love life, work

relationships and even her pocketbook. I found these scenes on the day-to-day economics

of her condition the most illuminating: she expounds on the cost of medication,

therapists, wigs, head coverings of different sorts. We also get fascinating

discussions on the hair of different races and ethnicities, as well as on the culture

and mythology of hair (Samson and Rapunzel are just the tip of the iceberg).

All this is

rendered in Jislová’s clean, almost schematic line that exudes a cartoony

dynamism. The book uses a two-color scheme of black lines with light reds to

produce numerous effects, like the “ghost hair” which Tereza has lost. (In

this, Bald recalls Georgia Webber’s split-identity techniques in her

2018 memoir Dumb: Living Without a Voice.)

The

author’s one-year journey as depicted makes for quite an emotional roller

coaster: despair rubs elbows with enlightened self-acceptance. A storytelling

workshop in Scotland proves cathartic. Tereza, like many people nowadays, seeks

solace on the internet, only to find confusion and – who’da thunk? –

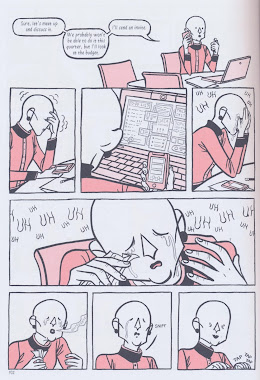

misinformation. A brilliant page design reifies her anxieties and stresses into

a fractured three-tier portrait as our narrator tries desperately to forestall

the inevitable with useless pills and creams. Another rather chilling episode

portrays her at her job, “dealing” with her hair loss by trying to ignore it

with overwork. Over eight panels, she melts down in tears before her laptop,

then resumes typing with a smile. Finally, another portrait, a splash, shows

her weeping on an armchair as supportive comments roll in after her first

posting online about her alopecia. This brief catalogue gives a sense, I hope,

of Bald’s dizzying affective spectrum. Overall, it paints a powerful

picture of physical difference and its mental health/social/cultural

ramifications in late capitalism.

The

author’s one-year journey as depicted makes for quite an emotional roller

coaster: despair rubs elbows with enlightened self-acceptance. A storytelling

workshop in Scotland proves cathartic. Tereza, like many people nowadays, seeks

solace on the internet, only to find confusion and – who’da thunk? –

misinformation. A brilliant page design reifies her anxieties and stresses into

a fractured three-tier portrait as our narrator tries desperately to forestall

the inevitable with useless pills and creams. Another rather chilling episode

portrays her at her job, “dealing” with her hair loss by trying to ignore it

with overwork. Over eight panels, she melts down in tears before her laptop,

then resumes typing with a smile. Finally, another portrait, a splash, shows

her weeping on an armchair as supportive comments roll in after her first

posting online about her alopecia. This brief catalogue gives a sense, I hope,

of Bald’s dizzying affective spectrum. Overall, it paints a powerful

picture of physical difference and its mental health/social/cultural

ramifications in late capitalism.

As Čechová told

Czech Radio, “I was really worried that the result would seem depressing,

because the comic does describe something that is very difficult. But it also

brings with it a lot of funny moments. We wanted to show that even if you go

through something like this, the world doesn’t fall apart” (Jančíková, “Cesta”).

Yet even the “funny moments” tend to have their edge. At one point, Tereza’s

boyfriend tells her, “The hair is fine. But not having eyebrows is creepy.”

Given that one of Tereza’s fears is living life alone due to her hair loss,

that comment seems less than reassuring.

Other moments I

found borderline disturbing. Trying to make herself feel better about her

condition at times leads to some dark corners, like this statement, which

sounds lamentably eugenicist: “I often think we had it coming. Humans no longer

need their hair. It’ll disappear in time. Evolution. Maybe I’m a member of a

new … more perfected race. But let me tell you, it’s not easy being one of the

first.” This textbox accompanies another portrait, of a half-naked Tereza

crying in the mirror.

Something else

which some may find rather distancing about Bald: what at times seems

like a willful opacity. By that I mean the text proceeds with great economy,

with an average of only about 20-25 words per page. It’s almost telegraphic.

This puts more of a burden on the art to carry the narrative, which Jislová

does more than capably. However, some choices have the effect of keeping the

reader (this one, anyway) at arm’s length. Jislová’s figures do not have eyeballs,

just black dots for eyes, and a puppet-like angularity to them (Tereza’s nose

looks like a sort of stylized diamond or arrow point). This choice risks

narrowing the expressive latitude of the characters, like watching a drama

acted out with dolls. (Maybe Jiří Trnka dolls? Though a lot of them had

eyeballs.) So that when Tereza has tears streaming down her cheeks it might look

to some readers as simply grotesque, and be less likely to provoke empathy/understanding.

Something else

which some may find rather distancing about Bald: what at times seems

like a willful opacity. By that I mean the text proceeds with great economy,

with an average of only about 20-25 words per page. It’s almost telegraphic.

This puts more of a burden on the art to carry the narrative, which Jislová

does more than capably. However, some choices have the effect of keeping the

reader (this one, anyway) at arm’s length. Jislová’s figures do not have eyeballs,

just black dots for eyes, and a puppet-like angularity to them (Tereza’s nose

looks like a sort of stylized diamond or arrow point). This choice risks

narrowing the expressive latitude of the characters, like watching a drama

acted out with dolls. (Maybe Jiří Trnka dolls? Though a lot of them had

eyeballs.) So that when Tereza has tears streaming down her cheeks it might look

to some readers as simply grotesque, and be less likely to provoke empathy/understanding.

Furthermore, Čechová’s

low word-count writing has a similar coldness and detached matter-of-factness,

even when discussing depression, social anxiety, desire. The author seems to

acknowledge this stance in a scene where she and her boyfriend are having

trouble communicating. “How hard it is for me to talk to anyone about my

feelings,” she says in a caption. Finally, I would have appreciated it if Bald

had interrogated the class conditions underlying Tereza’s experiences; this is

a very middle-class portrait of alopecia, despite the occasional nods to how

people without Tereza’s privileges might fare very differently in contemporary

Czech society.

These quibbles

aside (which in any case might have more to do with my own tastes as a comics

reader), Čechová and Jislová’s graphic memoir deserves its reputation for

taking Czech comics where they had never ventured before – potently so. As Kořínek

himself put it, in a quote highlighted on Paseka’s web page devoted to Bald:

“Frankly authentic, light-hearted storytelling, in the context of Czech comics,

feels a bit like an epiphany.” All this and cartoony anthropomorphic white

blood cells too!

More than

anything else, as a graphic memoir, Bald secures Czech comics’ further

imbrication with global comics culture. Paseka itself leans into this facet on

its web page, claiming the work “continues the rich tradition of

autobiographical comics from around the world.” Transnational comics flows

(analyzed so well by scholars like Daniel Stein and Kate Kelp-Stebbins) make

such a work as Bald all but inevitable, it seems.

Its authors,

both born in the post-communist 1990s, represent a younger generation much more

closely tied to graphic narrative beyond Czechia’s borders, to say nothing of

Central/Eastern Europe’s. Jislová told me she greatly admires Tillie Walden,

Kate Beaton, Alison Bechdel and Ulli Lust, global stalwarts all. This makes Bald

a work that is very self-aware about the non-Czech traditions that it’s tapping

and incorporating. “We felt, as we were working on the book, that this is the

first time we’re doing something like this in the Czech comics scene [on this

scale],” she said (Jislová interview).

More than

anything, the graphic memoir genre gave Čechová and Jislová a framework for a

story that they felt had to be told this way. “I’m a big fan of

autobiographical comics,” said Čechová, “because they can debunk (detabuizovat)

many things and reveal that which we’re not used to talking about. That’s why I

started to think that something could come from my experiences” (Jančíková,

“Cesta”).

The genie is

definitely out of the bottle now. Working on Bald led to Jislová first

hitting on the idea of pursuing her own autographical work. The result was her

own graphic memoir, Srdcovka (2023). The title is a hard-to-translate

slang term that means basically something close to one’s heart and/or that

inspires devotion/obsession. It deals with heartbreak, growing up as part of

the first generation after communism, sexual abuse and artistic coming of age. Heartcore,

the book’s English translation, is due to appear later this year (also from

Graphic Mundi, with Kuhlman again translating).

Apart from the

authors, the US press and translator deserve praise for bringing this work to

an English-speaking readership. We on these shores are chronically,

disgracefully bereft of translations of the world’s many vibrant comics

cultures, especially those with less common languages like Czech. Thank you.

Kuhlman told me that she and Graphic Mundi had decided on Bald (instead of, say, “Hairless”) for the translated title in part because the English word resonated with “bold.” That adjective, though not at all implied in the original Czech, nonetheless applies to this book – in more ways than one.

Bibliography

Jančíková, Šárka. “Cesta

hrdinky. Autobiografický komiks Bez vlasů o zkušenostech s alopecií se

nebojí těžkých témat ani humoru.” Český rozhlas (November 2, 2020). https://vltava.rozhlas.cz/cesta-hrdinky-autobiograficky-komiks-bez-vlasu-o-zkusenostech-s-alopecii-se-8352800.

Kořínek, Pavel. “Facets of Nostalgia: Text-Centric Longing in Comics and Graphic Novels by Pavel Čech.” Comics of the New Europe: Reflections and Intersections. Eds. Martha Kuhlman & José Alaniz. University of Leuven Press, 2020:

Interview with Štěpánka Jislová. Prague. June, 2024.

Paseka web page devoted to Bez

Vlasů. https://www.paseka.cz/produkt/bez-vlasu/

[1] Tereza Čechová (née Drahoňovská) (b. 1990) studied journalism and media sciences at Charles University in Prague. She and Jislová established the Prague branch of Laydeez Do Comics, a British women-led comics organization which advances the work of female comics-makers.

[2] Štěpánka

Jislová (b. 1992) is a graduate of the Ladislav Sutnar Faculty of Design and

Art in Plzeň. She has published in several Czech and international comics collections.

She also contributed to the monumental history comics series The Czechs

(Češi, 2013-2016) and illustrated the graphic biography Milada Horáková (2020),

written by Zdeněk Ležák. Her more recent work includes the superhero satire Supro:

Heroes on Credit (Hrdine na dluh, 2023).

[3] Full

disclosure: Kuhlman is a friend; we co-edited the collection Comics of the

New Europe: Reflections and Intersections (University of Leuven Press,

2020). She provided me with a copy of Bald for review.

[4] Penn

State published my 2019 co-edited study, with Scott T. Smith, Uncanny

Bodies: Superhero Comics and Disability.

Graphic Novel Review: Sunday, by Olivier Schrauwen

Olivier

Schrauwen, Sunday. Fantagraphics, 2024. US $39.99. ISBN: 9781683969679. https://www.fantagraphics.com/products/sunday

Highly regarded Belgian cartoonist Olivier

Schrauwen is known for producing both short- and long-form comics that combine

moments of absurdity and surrealism with in-depth characterisation that often

depict the inner lives of men living in isolation. He

brings a new level of depth to this type of character study in Sunday, a

472-page graphic novel from Fantagraphics.

Sunday is

regarded by many cultures as a day of rest, relaxation, and contemplation. In

his eponymously-named graphic novel, Schrauwen depicts a fictionalised account of

the life of his cousin, Thibault, a thoroughly ordinary man, on a largely uneventful

Sunday. By offering a nearly minute-by-minute account of Thibault’s

physical experiences and mental processes between 8:15am, when he awakens, and

midnight, Schrauwen invites the reader to inhabit the world, and consciousness,

of his protagonist. In this way, his approach is reminiscent of early Modernist

novels, including Mrs Dalloway and Ulysses, both of which were

set in a single location on a single day, and are particularly remarkable for

their use of interiority, which creates a level of intimacy and identification

with their lead characters. According to notes provided by Schrauwen in his

introduction, he was attracted to the project because it would give him the

opportunity to use the comics medium to create something ‘beautiful’ from what

his cousin Thibault described as a ‘wasted day’. Such days are those filled

with ‘procrastination, aimlessness and boredom, in which [Thibault] failed to

do anything edifying’.

In trying to

find a way to describe how Schrauwen achieves this feat, it might be most

appropriate to look at music. Certainly, music features in the graphic novel

explicitly. Thibault wakes up with the song ‘Sex Machine’ in his head, an

ironic theme song to the first two hours of his day given what can only be

described as his ambivalent relationship to actual sex with his girlfriend, Migali,

a visual artist who is on her way home after weeks spent engaged in

collaborative art in an unnamed African village. While she has been immersed in

African culture in reality, the closest Thibault gets is playing West African

music on his turntable while imagining the band surrounding him in his unremarkable

apartment. Another live music performance is featured when Nora, a previous

love interest of Thibault’s, and Thibault’s cousin Rik, are depicted attending

a piano concert, while – much later – a parallel is drawn between a mole on

Nora’s face and the symbol for a pause in musical annotation.

However, the

graphic novel’s musical connection runs deeper than these explicit references

to artists, bands, and musical notation. Like a conductor on a stage, Schrauwen

has utilised words, images, and the spatial elements of the page control the reader’s

perception and experience. Indeed, Schrauwen is ever-present within the text.

In the introduction, he provides ‘reading instructions’, along with a

self-portrait, and later appears as an illustrated version of himself, to offer

a brief commentary on his cousin’s character. Schrauwen’s illustration style is

equal parts impressionistic and realistic, like a rough and slightly naïve

rotoscope. Spatially, while he has chosen to depict the world of the text

largely from eye-level in a series of close-ups, mid-shots and wide shots of

the type familiar to filmgoers, there are instances of more dynamic

representation, as the camera floats above our protagonist and even tours the

galaxy, the latter a product of Thibault’s fantastical imaginings.

Reinforcing the

link between layout and Thibault’s subjective experience, when he smokes marijuana,

the panels depicting the experiences of the secondary characters whose

experience he is not privy to, become far less linear. Some panels snake around

the page, while the frames of others melt and merge together. At the same time,

the page numbers become unmoored from their usual place at the bottom of the

page, rearranging themselves almost randomly before disappearing altogether. Thibault’s

thoughts are similarly jumbled, with some of his words appearing enlarged,

making them impossible to read, while others run in circles and even backwards.

It is in these moments that Sunday’s most outstanding – and most musical

– feature can be seen clearly. This is what Daniel Albright has referred to as

Modernist music’s ‘testing of the limits of aesthetic construction’.

In these ways, this graphic novel defies categorisation. It is a depiction of banality that is anything but banal, and an exploration of the life of an unremarkable man that is nevertheless remarkable. In this way, it’s a book about all of us … whether we’d like to admit it or not. Thibault (or perhaps it is Olivier Schrauwen, speaking through Thibault) says as much when he suggests, ‘I’m holding up a mirror … so you can recognize your flawed selves.’ Sunday shows how, when viewed from the right perspective, what might otherwise be dismissed as a ‘wasted day’ can have value and – yes – even beauty.

Tuesday, January 21, 2025

An Evening with Jules Feiffer at the Cosmos Club in 2007

The great cartoonist Jules Feiffer has passed away. IJOCA ran this interview in print in Fall 2008.

An Evening with Jules Feiffer

By Alan Fern

The late Dr. John P. McGovern established an award program

at the Cosmos Club Foundation in

Transcribed by Michael Rhode, from a tape provided by the

Cosmos Club.

Thursday, January 9, 2025

Graphic Novel Review: Woman & Man+

Craig Yoe. Woman & Man+. Clover Press, 2024. https://cloverpress.us/products/woman-man

Craig Yoe is best known as an editor and publisher of archival comic book compilations (usually those that have fallen out of copyright) that he put together under his own imprint Yoe Books and for other publishers like Abrams, Fantagraphics, IDW and Dark Horse. He has not drawn a comic book for decades, but since moving to Bagio City in the Philippines recently, he has come out with Woman & Man+.

The backmatter of the book encourages an autobiographical reading: "A wildly surreal autobiographical story of Yoe losing his love, his country, and some say - his sanity - and his struggle to reinvent himself." Yoe himself proclaimed, "This humble underground comix / pretentious-art book is a psychedelic telling of my fleeing the U.S. to hook up with the underground comix comrades in Berlin, then booted out of Germany to find solace - then devastating heartbreak - in the Canary Islands. Finally the Philippines have granted me asylum... and hope." In his introduction, Yoe explains he was mentally and emotionally in a bad place where he had no choice but to draw Woman & Man+ to survive and to find hope. Thus, this book is art therapy.

One would be hard-pressed to see the above-described journey of NY-Berlin-Canary Island-the Philippines in the art and story. As described in the backmatter, it is a surrealistic landscape of Dali and Hieronymus Bose mixed with Robert Crumb. Animation Magazine described this book, "like Dr Seuss on acid!" It is pop art by way of 1970s underground comix (the period when Craig started doing comics) as we have Minnie Mouse, Batman (Adam West), Nancy, Snoopy, Korky the Cat and even Mr Monopoly made their guest appearances. The art is reminiscent of Keiichi Tanaami, but without the vibrant colors. It is closer to what the late Rick Griffin (an old friend of Craig's back in the day) or S. Clay Wilson may have done if they were still alive, and working with the heavy black and whites. In a way, Craig is the link between the 1970s underground comix and the 2000s alternative comics of Dave Cooper. Craig's position has always been that comics are not meant to be taken too seriously. They are not high art but rather, in this book, it is “Yoe-brow.”

The bottom line: the way to appreciate Woman & Man+ is to let its stream of consciousness sweep over you and go with the flow. Is it about the eternal struggle between the passions of men and women? Maybe. Some might want a stronger narrative structure like the wordless comics of Phil Yeh (another artist of Craig's generation), but we should take Woman & Man+ as it is. Craig is approaching his mid-70s soon. It will be a pity if he does not write and draw more at this late stage of his career. Maybe the cool air of Bagio City will do him some good and we will see more of his art.