Spirou dans la tourmente de la Shoah. Didier Pasamonik and Caroline Francois. Mémorial de la Shoah, Paris. December 9, 2022 - August 30, 2023.

|

Image by Emile Bravo used for the main poster of the exhibition and its catalogue

|

Since

opening in 2005, the Mémorial de la Shoah

in Paris programs two

temporary exhibitions each year to complement its permanent exhibition

that traces the history of French Jews during the Holocaust. On January

19th 2017,

the Mémorial launched its first temporary exhibition that explored the Holocaust as recounted, confronted and contemplated

through comics. Shoah et bande dessinée

offered an historical, artistic and cultural overview of the different

ways and forms that comics engaged with this most challenging of

subjects through fictional and non-fictional lenses. The success and

popularity of the exhibition - which included supplementary conferences,

meetings, film projections and a reading library that offered almost

every title referenced in the exhibition - prolonged its duration well past its

original October 30th 2017 closing date, finally ending on January 7,

2018.

Five

years later, comics have once again returned to the Mémorial for

another temporary exhibition, this time focusing on a singular work

featuring Belgium's famous bande dessinée bellboy Spirou. Under the

scientific commission of Didier Pasamonik (who also played a major role

in realizing Shoah et bande dessinée), this new exhibition illuminates

the different historical contexts that inform the wartime adventures of Spirou as written and drawn by Emile Bravo. Over

the course of the four albums that make up L'ESPOIR MALGRÉ TOUT

(HOPE DESPITE EVERYTHING), Bravo takes readers alongside his version of

Spirou through a journey of awakening that forces the young bellhop to

face the harsh realities of the Second World War through the plight of

Felix Nussbaum and Felka Platek, two real-world Jewish artists whom he

befriends while they hide in occupied Brussels. This intertwining of the

fictional characters of Spirou (and his companion Fantasio) with the

real-life figures of Felix and Felka in their real-world context

provides Bravo with a rich tapestry to open a dialogue with Comics, History and

the Holocaust in a deeply personal fashion.

Taking Bravo's bande desinnée as its starting and framing point of departure, the exhibition digs into the historical contexts that are evoked and referenced

throughout his

330-page Spirou tetralogy: the Occupation,

Deportation, Resistance and the Shoah as they were experienced in Belgium. By exposing these contexts, the

exhibition actually illuminates parallel stories of humanism in the face of war: one centered on Emile

Bravo's Spirou comics themselves, the other focused on Le journal de Spirou, the

weekly comics magazine that introduced its eponymous hero in 1938. With a wealth of supporting archival material that includes original

artwork by Felix Nussbaum and Felka Platek, the exhibition reveals the fascinating negotiation between comics fiction and historical fact that engages with the Shoah through the morality and empathy of Spirou and Emile Bravo. It is through this optic that L'ESPOIR MALGRÉ TOUT is presented as an ideal vehicle to transmit the memory of the Shoah across a generational audience, leading Didier Pasamonik to boldly hail Emile Bravo's magnum opus as "the most important comic written about the Shoah since Art Spiegelman's MAUS".

|

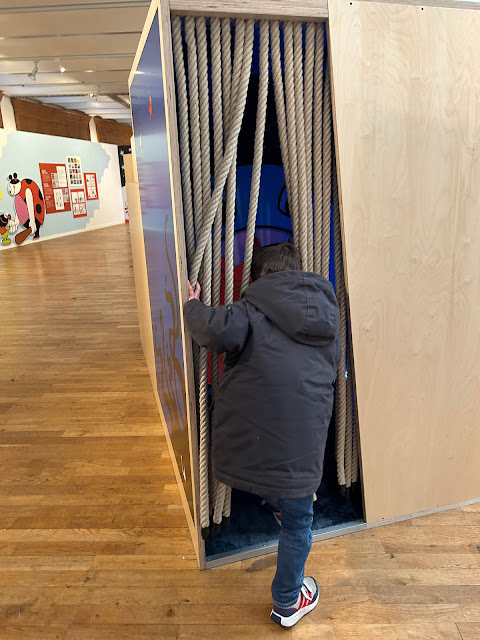

Entrance to the exhibition with a visual guide to introduce the different interpretations of Spirou since his creation

|

Spirou dans la tourmente de la Shoah is divided into twelve sections installed across two adjacent

rooms that are connected by two short separate halls. The first room houses seven sections and one centerpiece that anchors visitors first to Emile Bravo and his take on Spirou, then progressively delves into the real-world contexts that inform the narrative.

|

Section 1: Emile Bravo's SPIROU

|

Watch the opening interview clip with Emile Bravo.

|

| Section 2: Belgium in the War |

|

| Section 3: Spirou and Fantasio meet Felix and Felka |

|

| Section 4: Undesirables |

|

| Section 5: Belgium Under the Occupation |

|

| Section 6: Resisting |

|

Section 7: The Persecution of Jews in Belgium

|

Each

section is always introduced with a page excerpted from the

comics, followed by expository text enhanced by captioned archival documents,

newspaper clippings, photos, film clips, wartime propaganda, maps and

artifacts. What is illuminating about the organization of the information is how the interplay between fiction and fact suggests the natural manner that Bravo negotiates their relationship in his comics without didactic overplay or overt signaling. L'ESPOIR

MALGRÉ TOUT is very much a coming-of-age story told from the child's

perspective of Spirou, so his character experiences much of this

information that is presented in the sections about Belgium in the War

and under Occupation. One

of the most sobering aspects on display in the third section are the identity documents of Felix Nussbaum and Felka Platek alongside a reproduction of an abstract painting of them by Nussbaum. Their juxtaposition functions as stark testament to their real-world

existence, and is extended one dimension further in the face of the centerpiece display of Emile Bravo's

original pencil sketches and page layouts for Spirou's

meeting up with them.

The fourth section on the "Undesirables" also illuminates the little-discussed existence of the internment camps in France that held German civilians living on French and Belgian soil during the earliest months of World War II. Visitors are first introduced to the Saint-Cyprian camp located in the French Pyrennes and learn that this is where Felix Nussbaum was interned in 1940 before eventually escaping to Brussels. During his imprisonment, Nussbaum created several works of art to express the physical, emotional, and spiritual turmoil that he witnessed and endured. Reproductions of two of his paintings are on display here, and they may be familiar to readers of L"ESPOIR MALGRÉ TOUT since Bravo smoothly integrates them into his comics as a way to enlighten Spirou (and by proxy, the reader) of the harsh reality of French and Belgian wartime politics. The camp at the nearby Argèles-sur-mer is also highlighted, and the visitor learns that many Spanish Republicans fleeing the Franco regime were interned there, among them the father of Emile Bravo himself, whose identity card and photos taken during his time there attest.

|

The first room centerpiece featuring original artwork by Emile Bravo.

|

The sixth section about Resisting not only sets the context for Spirou's moral and ethical awakening, it also introduces Le journal de Spirou and its editor-in-chief Jean Doisy - the pseudonym of Jean-Georges Evrard- as exemplars of Resistance itself. With the help of newspaper clippings, correspondence, and ads and comics from Le journal de Spirou, the exhibition highlights the open yet clandestine efforts in which children were being directly addressed to keep true to a code of honor as an "ami de Spirou". One of the most important vehicles of this direct address, both in comics fiction and in historical fact, was the Traveling Farfadet Puppet Show starring Spirou himself, and the exhibition displays an actual historical Spirou puppet alongside actual posters, sheet music, promotional pamphlets and historic film clips for the show. There are even postwar newspaper clippings attesting to the importance of this puppet show and its puppeteers in saving many Belgian Jewish children. Installed on the backside of the first room centerpiece, the puppet display is fittingly placed to face the Resisting section to spatially capitalize on their thematic relationship. This section is quite rich in terms of presenting historical information that offers visitors a new window to consider Spirou, both the character and the magazine. Considered in this new light, their creation and activity during the war years holds a deeper resonance as a transmitter of hope and resistance, one that Bravo brilliantly evokes in his comics.

|

The Farfadet Puppet Show featuring Spirou on the back end of the first room centerpiece.

|

Exiting the first room through the short hallway at the back leads to the eighth section of the exhibition: the Deportation Trains. The

use of trains in ESPOIR MALGRÉ TOUT is always accompanied by a sense of

dread and the unknown, to the point that Bravo begins and finishes

each of the four albums with scenes

involving trains or railway stations.

|

Section 8: The Deportation Trains

|

Though it is a relatively short section in terms of presentation and display of historical information, it makes the explicit point of the existence of deportation trains in the city of Mechelen, where Jews and Roma were held in military barracks (the Kasserne Dossin) before being shipped off to Auschwitz-Birkenau. Photos, passenger lists, registration plates and inventories of meals given to deportees on the day and eve of their departure are presented as a sobering testament of the systematic administrative process behind what was for many to be their final train ride to the East.

|

The two rooms connect via a hallway that houses the section about the deportation trains

|

The second room is grounded in the historical reality of the visitor, that is, the reality outside of the pages of Spirou. At about three-quarters the size of the first room, it holds four sections that consider the grim reality of the historical backdrop of Bravo's story, as well as a consideration of the history and role of comic books during these dark years.

|

| Section 9: What's Happening in the East |

|

| Section 10: The Painter's Gallery |

At first glance, the second room of the exhibition seems less packed with original pages and artifacts on display, but a closer look shows that this is not a situation of lack of content, rather it is a thematic decision to focus exclusively on the real-world contexts both outside of and after the pages of Bravo's Spirou. The ninth section examines the growing awareness of what was happening to the East with the deportations, introduced by an excerpt from the comics that shows Spirou's awakening to the same horrible fact. Here we are introduced to Victor Martin, a member of the Belgian Independence Front who went under cover on behalf of the Jewish Defense Committee to investigate what was happening to the deportees. The report that he brought back to Brussels after a series of arrests and interrogations confirmed that the unbelievable rumors that were circulating about forced labor and death camps were fact. Through documents attesting to the veracity of his mission and his identity (including his false identity papers), as well as select pages of his report that eventually made its way to the Belgian government-in-exile in London, this section not only is succinct in confirming the reality of atrocity, it also helps set the tragic tone to digest the next section.

The Painter's Gallery (see photo above for Section 10) opens with five different panels taken from L'ESPOIR MALGRÉ TOUT where Spirou visits Felix in his Brussels studio-in-hiding and sees some of his tableaux. Next to the comics panels are shown their real-world equivalents (in reduced scale reproduction) so visitors can see the moments when Bravo introduced and integrated these five actual paintings into his Spirou story and their progressive effect on his titular character. Immediately following are installation spaces for the display of original artwork by Felix Nussbaum and Felka Platek, courtesy of the Felix-Nussbaum-Haus in the Museumsquartier Osnabrük. Here visitors can examine in close detail some of the original artwork of Felix Nussbaum in their original scale, size and texture.

|

Felka Platek's portrait painting (top) overseeing Felix Nussbaum's separate portraits of Felka (left) and himself in 1940 (right)

|

A

lone full-size portrait painting by Felka Platek of an unnamed woman is

also displayed to remind visitors of the dual tragedy of the loss of

these artists and human beings. It is documented fact that in 1944, both

Felix and Felka were arrested in Brussels, detained at the Kaserne

Dossin in Mechelen, and deported by train to be murdered in Auschwitz.

None of these facts about the fate of Felix and Felka are raised by

Bravo in his comics as it all deliberately occurs "offscreen". In Bravo's words, he wanted to make clear that their death would not be at the hand of the author, it was our reality that killed Felix and Felka. That

said, this section shows that, to the great failure of the Nazis, the

traces of Felix and Felka's existence are memorialized through their own

artwork to the point of inspiring Emile Bravo more than sixty years

later to bring them back to life.

|

Nature morte d'une mannequin (1942), left, and Atelier à Bruxelles (1940), right, by Felix Nussbaum.

|

|

A portrait of Felix Nausbaum by Sad Ji (top) overlooking two pencil drawings by Felix Nussbaum drawn near the end of this life.

|

The final two sections respectively deal with the fate of Le journal de Spirou following the Liberation, and the situation of Franco-Belgian comics during the Occupation years. It's an interesting choice to close the exhibition with these two comics-centric sections (as opposed to finishing on a more emotional note such as the previous section) and it speaks to the curator's concerted attention to include comics history into this larger historical context to round out the concerns that this exhibition has chosen to deep dive into.

|

| Section 11: A Comic Book in History |

With a sequence showing the Liberation of Brussels taken from the final part of L'ESPOIR MALGRÉ TOUT to set the scene, the eleventh section paints an atmosphere of rebuilding and reprisals in the wake of the Nazi defeat. Given Jean Doisy's activities in the Belgian Resistance as recounted in the sixth section of the exhibition, Le journal de Spirou was able to reappear on newsstands and start on a strong enough footing to soon usher a Golden Age of of the magazine with the likes of André Franquin and Will Morris at the drawing board. Using the display of Liberation-era ephemera, photos, recordings and official correspondence and attestations in support of Jean Doisy and others associated with Le journal de Spirou, the political contextual relationship between the era and the magazine is convincingly established. This was not the case for all comics and comics creators in the Franco-Belgian scene as the twelfth and final section outlines. Presented on both sides of the centerpiece (one for France, the other for Belgium), actual comics and newspaper strips from the Occupation era such as Journal de Mickey, Coeur Vaillant, and Bravo! are displayed as examples of how certain comics thrived or survived in those countries. Questions of collaboration with the Occupying forces are raised with respect to certain authors, most notably Hergé, whose mug shot is displayed in a fascinating piece of Resistance ephemera titled "Galerie des Traitres". In France, Jewish-owned comics publishers were often the target of antisemitism. Some publishers were immediately "aryanized" whereas some moved production to Marseilles in the Free Zone, where their distribution was contained to that geopolitical borders. These challenges, alongside the eventual rationing of paper, are all evoked here in a rudimentary sense but offering a necessary base to give enough context to conclude the tale of the two Spirous, with enough material to suggest further contemplation (perhaps as the subject of an entire exhibition unto itself).

|

| Section 12: The Comic Book under the Occupation in Belgium and France |

The exhibition closes off with a final wall that offers two closing remarks in summation. The first is a quotation in its original French and translated into English that leaves the visitor with no question as to the canonical status of Emile Bravo's accomplishment with Spirou from the perspective of the Academie Francaise.

|

The second-to-last closing statement about L"ESPOIR MALGRÉ TOUT, from Pascal Ory of the Academie Francaise.

|

The final word naturally ends with another interview with Emile Bravo that serves as an appropriate bookend to bring the visitor back to where the exhibition started with his opening words.

Watch the closing interview with Emile Bravo

The exhibition is accompanied by an excellent 160 page catalogue published by Dupuis that contains wonderful color reproductions of many of the elements on display. The information presented in the exhibition is taken up and expanded upon in illustrated essay form by a variety of specialist authors. It is an excellent companion piece that sits perfectly on the shelf next to the four volumes of L"ESPOIR MALGRÉ TOUT.

|

The

exhibition catalogue (center) surrounded by the four albums that

recount L'ESPOIR MALGRÉ TOUT

|

|

Table of contents of the exhibition catalogue

|

To suggest that one leaves this exhibition learning something new is an understatement. The vast wealth of information on display is arranged and organized in a comprehensible academic fashion that evokes a solid DVD supplementary section authored by the Criterion Collection. Far from being a simple presentation of Emile Bravo's research notes and preparatory sketches and outlines, Pasamonik and Francois have curated this exhibition as an interpretative act of reading. Emile Bravo himself stated at the vernissage of the exhibition that he was genuinely surprised by how much was information and material were being drawn from his work for this museum display, and he admitted being unsure as to whether there was enough material to merit such a project. Without question, this exhibition offers more than enough to see, read and contemplate in such a small compact space, leaving visitors with the desire to not only appreciate Emile Bravo's Spirou albums, but to re-read them with a wider conscience, and perhaps look further into the life and work of Felix Nussbaum and Felka Platek, for an even richer experience than before. That in itself is a fitting testament to both this exhibition and the work of Emile Bravo.

- Nick Nguyen

All photos taken by Nick Nguyen

P.S. For the completists, please find below a collection of all the photos of the exhibition that I managed to take to give readers an idea of the spatial layout and organization of the exhibition. I've tred to include all of the elements on display, though not all of them are in close-up.