by Wim Lockefeer; photos by Nick Nguyen

Founded in 1992 as the Luzern Comix Festival, the Fumetto International Comics Festival can rightfully call itself one of the most important comics events in Europe, along with the Festival Internationale de la BD in Angoulême (France), Lucca Comics and Games in Lucca (Italy), and the Erlangen Comics Salon (Germany). Over the years, many internationally-renowned creators attended the festival, including Edmond Baudoin (the Festival’s first creator in residence), Jack Kirby, Daniel Clowes, Ulli Lust, Robert Crumb, Jacques Tardi and Emil Ferris. Additionally, the Festival has proven to be instrumental in bringing comics scenes from various Swiss language communities together.

Pandemic

As a direct result of the Covid-19 pandemic and national and international measures to counteract its spread, the Festival had to cancel its 2020 edition, as was the case for most public gatherings of that time. The 30th anniversary of the festival was celebrated in a hybrid format, with events organized in the city of Luzern, as well as online with the Comic Chat Café and a virtual exhibition.

This year’s edition (2022) was supposed to be a joyous return to form, with a full-fledged festival all across the city of Luzern. Whether the organization would be able to pull this off remained uncertain until about two weeks before the starting date, when program information was finally published on the Festival’s website. Most likely this delay was as a result of the uncertainty regarding international Covid-19 measures, and how this might affect the possibility of international guests to even attend the Festival. After all, only days before the opening, Switzerland radically reduced its pandemic regimen, but even so, various international visitors were unable to attend.

Kornschütte

More than ever, the Festival was centered around the Kornschütte, an old official building in the center of the city that is often used for cultural events. The building hosted the main information hub, as well as a small bookstore with selected new comics, predominantly from Switzerland and Germany, including Strapazin, Switzerland’s leading comics magazine. The room also hosted a craft market, where small press publishers, printmakers and other creative types hawked their wares. In a corner cartoonist Julietta Saccardi presented her Tiny Tragedies project, a series of minicomics based on true stories of sexual abuse and harassment.

|

| Julietta Saccardi's Tiny Tragedies |

Five exhibitions were housed in and around the inner city, with two smaller ones devoted to the Swiss comics magazine Ampel and French Edelporn publisher BD Cul (which, true to form, was designed as the aftermath of a very dodgy party, with empty bottles, condom wrappers and assorted paraphernalia strewn around the room). Similarly small in size was the exhibition on French cartoonist Emilie Gleason, this year’s artist in residence.

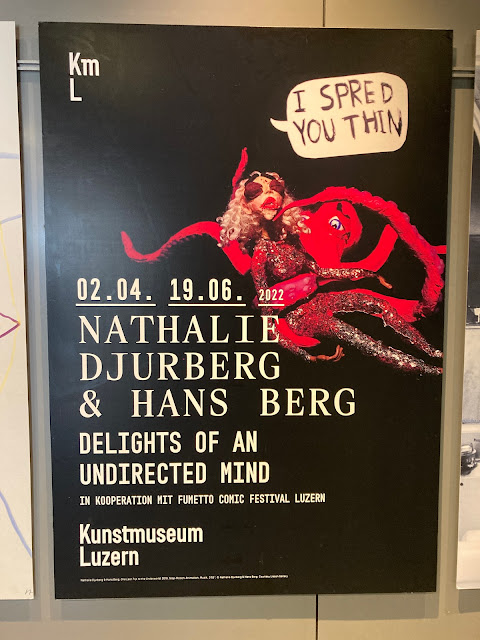

A bit more ambitious was the presentation in the Kunstmuseum of a selection of video artworks by the Swedish duo Nathalie Djurberg and Hans Berg, famous for their idiosyncratic, rowdy and often disturbing stop-motion animation centered around desire, lust, and the inevitability of human decline. Their work typically features grossly deformed personas that prey upon one another, are taken apart and then reassembled or simply wander around to their impending doom, accompanied by soundscapes that, thanks to the setup of the exhibition, blended together in an almost hypnotic, alienating experience. Even though its link with comics as such may have been tenuous, it was a strong show, both artistically and in terms of message.

Zorro

Plenty of comics content was present in Peter Poplaski’s The Curse Of Zorro exhibit, the Festival’s main event and housed in a rather dilapidated old warehouse. For his show, the American cartoonist selected a large number of items from his personal collection, as well as original artwork from himself and other cartoonists, to sketch an alternative history of the (super-) hero as the typical archetype of the Twentieth Century. While Poplaski’s main argument, that modern superheroes are the direct descendants of ancient gods' pantheons and of the characters from late medieval chivalry, and play the same role as aspirational examples, may be tenuous, disputable and quite likely very American-centered, the show itself was interesting and entertaining, with numerous old editions of Zorro stories (Poplaski’s personal favorite and obsession), as well as board games, action figures, movie posters and the like.

|

| Peter Poplaski's The Curse Of Zorro |

The long list of additional features and events on the Festival’s program proved to be mainly showcases of artists or books in various shop windows around the city, mostly without any context or information, and often so small you walked past looking for them before you knew it. One notable exception was the tiny but exquisite exhibition of original artwork that local cartoonist Pirmin Beeler had assembled with pages from his latest graphic novel, Das Leuchten Im Grenzland (The Glow in the Borderlands, Edition Moderne, 2022). With his delicate lines and subtle pastels, Beeler is a name to keep track of.

Even though separately these shows and events certainly were not without value, on the whole the Festival left this visitor rather unsatisfied, and constantly checking the program to see if he wasn’t overlooking anything, after all? Was this really everything, not just in numbers, but also in quality? Indeed, with the possible exception of the Djurberg-Berg presentation, none of the Festival’s offerings really went beyond just acceptable in terms of content, presentation or urgency. At the FIBD in Angoulême, the Poplaski show would at best have been an also-ran, a nice addition to the Festival’s main events.

|

| Pirmin Beeler' beautiful artwork |

Narrow?

It is unclear whether this year’s Fumetto attracted the 40,000 visitors that it boasted ten or fifteen years ago. We visited the Festival, which was said to run from April 2-10, during its first weekend when, indeed, there were some people around. The presentation of this year’s Stipendien (or grants) filled a small auditorium, and visitors did show up for the exhibitions. But there were no lines for the ticket booth or information stands, no throngs to wade through to see that one piece, no presence in the streets. On Monday, the Festival was basically dead.

Restarting a public event after a long and difficult period like the Covid-19 pandemic is a hard and risky endeavor. In the coming years Fumetto may indeed grow again to dimensions on a par with its reputation. The question, however, is whether that is the Festival’s current direction. 2022’s Festival clearly showed a narrow, quite exclusionary view on comics. Except for the book store, mainstream comics, and even literary comics aimed at a larger audience, were completely absent, while this year’s awards went to niche or activist cartoonists.

This analysis, of course, may be just Hineininterpretierung (German for interpreting in meaning that doesn't exist) from an unprepared guest who did not have the right expectations, or it could be an explicit, and doubtlessly meritorious view on what the Festival should be. Maybe the Festival’s directors feel that the Festival’s future in changing times, and a changing landscape, is not so much in inclusion, but rather in focus on specific audiences and themes, a smaller scale and an explicit view on artistic politics. But in my personal view, it would be unwise to limit the scope of one of the most venerated comics festivals in Europe to just that, especially in a time when the importance and weight of the medium as we know it is not what it used to be.

A version of this review will appear in print in IJOCA 24:1.